A funny thing happened to Tony Abbott’s public persona after Malaysia Airlines flight MH17 was shot down over Ukraine. Or rather, something happened to media accounts of how Australians see their prime minister.

According to the political commentary, Abbott’s firm response to the atrocity – his clear, simple language, his barely contained fury and his demands that Russia make amends – struck a strong chord with the public. This assessment emerged almost as soon as the prime minister had held his first press conference on the issue.

For his supporters, this was the Abbott they had always known, and now the rest of the country would know him too and embrace him. And the next few opinion polls did contain evidence to back this up, but only to a small degree. Abbott’s approval and satisfaction ratings improved a little, outside the margin of error, but remained (and remain) low. He’s still an unpopular prime minister by historical standards, particularly for one so recently elected.

Measured by two-party-preferred voting intentions, the government also staged a discernible but modest recovery, but it’s still the case that no poll published since early April has shown the Coalition ahead of Labor.

Yet once our political storytellers have their teeth into a narrative, it is difficult to stop them gorging on it. A lack of evidence isn’t enough. The fact that they believe Abbott is cutting a dashing figure on the world stage only adds to their tenacity.

Something unedifying possesses the Australian media when its gaze moves to this country’s place in the world. The national trait of wanting to see Australia “punching above its weight” overrides sober analysis. The elaborate protocols of international interaction are interpreted at face value and invested with earnest meaning. Journalists accompanying our leader overseas gush as the PM interacts, on equal terms, with this or that famous identity.

When the event is a one-on-one with the leader of the Free World, critical analysis disappears altogether. Formulaic declarations of trust and intimacy from the White House are latched onto in a desperate quest for validation. Back home, sweet nothings about our leader’s special place in the president’s heart, whispered into journalists’ ears by American ambassadors and other US officials, are faithfully ingested and repeated.

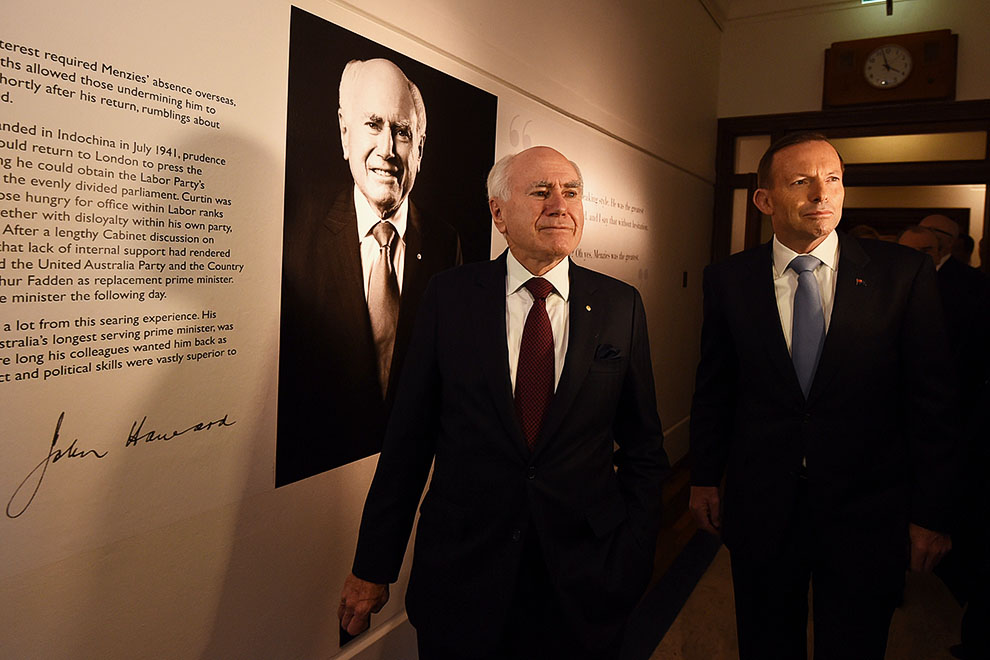

This syndrome reached its apogee with the John Howard–George W. Bush relationship around the time of the war in Iraq. Those two were extremely close, we were told – in fact, they were so tight that Bush rarely did anything without consulting our man first. Many Australian journalists and academics came to see the Iraq adventure as an American, British and Australian one, and some of the more excitable even excised Britain from that equation.

Which would have been news to everyone outside Australia. There, they were under the impression that the endeavour involved the United States and Britain, plus a couple of dozen others. Bush’s memoirs, published in 2010, barely mentioned the Man of Steel and brought some of the mythology thudding to earth.

It’s this vein that many are attempting to mine again. Already described in some corners of the commentariat as a “wartime prime minister,” Abbott is being presented as the guy who, in characteristic blunt Australian style, calls a spade a spade. He gets to the nub of the issue while overseas counterparts beat around the bush and indulge in diplomatic niceties.

One journalist even recounted Barack Obama telling aides “we need a few more Tony Abbotts in the world,” which reads like a discarded Aaron Sorkin first draft.

As with so much of politics these days, on both sides, the strategic template is Howard, but it is based on a dodgy, partial recollection of how he behaved and, importantly, the reasons for his electoral longevity. Howard’s political success came primarily from the booming economy, with its historically low interest rates and unemployment, overflowing budget surpluses and appreciating real estate. Most of the other tales, about “values” and “battlers” and “middle Australia,” were just hype. So many of the “lessons” drawn from that time were illusory.

Julia Gillard was a Howard aficionado. She attempted to repeat what she believed were the lessons of the Howard years – the importance of embodying suburban ideals and uncomplicated tastes, and speaking simply and clearly to voters. It proved disastrous and delegitimising.

Until now, Abbott has eschewed the conscious personality reinvention so favoured by his two immediate predecessors. But lately, in attempting to cultivate his own Man of Steel identity, the prime minister gives the appearance of playing to the opinion pages, and particularly the more fawning ones.

Like Howard’s, Abbott’s longevity will depend mostly on economic security and the public’s judgements about how both sides of politics will manage the economy.

Which is not to say national security doesn’t work for incumbents. But while there’s something appealing about the idea that Australians yearn for a straight-talking leader who puts international events simply and clearly (cue repeated references to “evil”), this view of politics relies on an increasingly outdated caricature of the voter.

The prime minister’s comparison of the Islamic State to communism and Nazism this week – and hence the reason to “respond with extreme force” – was touching on bizarre. And those insisting Abbott is earning plaudits around the world don’t seem to have checked whether the rest of the world is actually aware of this.

Politicians usually make a mess of things when they try to be politically clever – just ask Kevin Rudd or Julia Gillard. Mistaking the commentators’ adjudication for community sentiment is evidently a powerful temptation. One valuable lesson that can be drawn from the Labor years is that Australians want their leaders to behave like grown-ups. It’s worth keeping in mind. •