Thirteen years after the invasion of Iraq, the Chilcot inquiry report provides some definitive answers to Britons about how and why Tony Blair took their country to war. Chilcot acknowledges that Saddam Hussein was “undoubtedly a brutal dictator who had attacked Iraq’s neighbours, repressed and killed many of his own people and was in violation of the obligations imposed by the UN Security Council.” But he suggests that the “UK chose to join the invasion of Iraq before the peaceful options for disarmament had been exhausted. Military action at that time was not a last resort.”

The inquiry found that “the judgements about the severity of the threat posed by Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction, WMD, were presented with a certainty that was not justified” and that “despite explicit warnings, the consequences of the invasion were underestimated.”

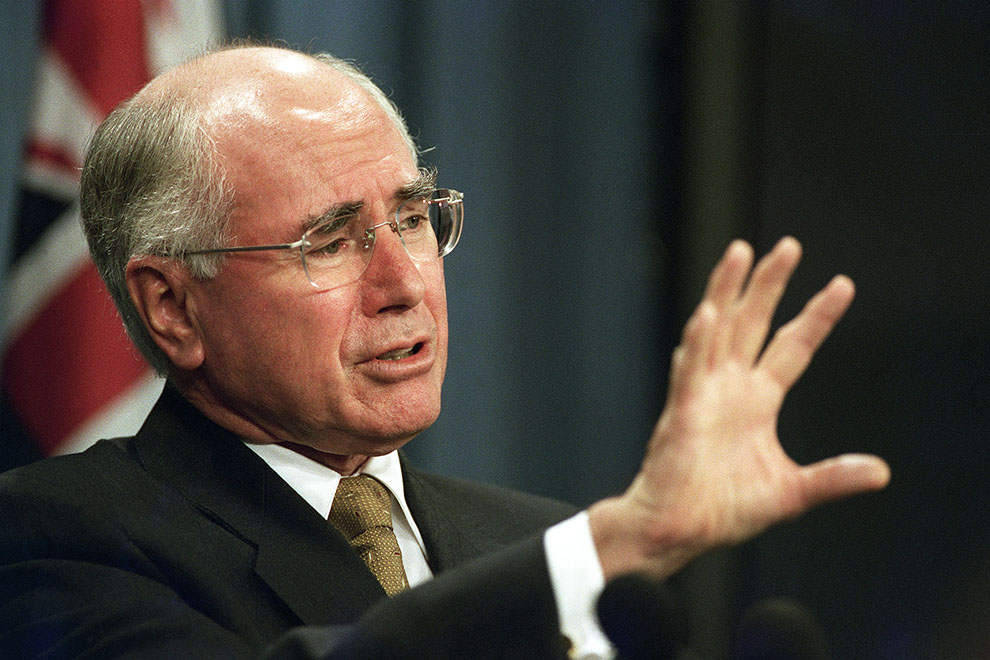

The sequence of events Chilcot describes has its parallel in Australia. From the early preparations for war through to the post-invasion excuse-making, George W. Bush, Blair and John Howard kept strictly to script. The reasons for going to war – principally the threat of a WMD-armed Saddam – were carefully coordinated in terms of timing and content.

In the war’s aftermath, there have been no admissions of guilt or wrong-doing. In response to Chilcot, Blair expressed “more sorrow, regret and apology than you will ever know” for the war’s outcome. He apologised for the failures in planning, but maintained that he had not misled his country: that he had taken the right decision and that it was taken in good faith. In his National Press Club speech this week, Howard, too, maintained that he had made the right decision but that the intelligence was flawed.

In Britain and Australia there have long been questions about when, and on what terms, Blair and Howard committed British and Australian military support to Bush. Chilcot found that Blair had agreed to provide British troops long before he acknowledged it publicly, writing to Bush in July 2002 that “he would be with him ‘whatever’ – but if the US wanted a coalition for military action, changes would be needed in three key areas: progress in the Middle East Peace Process; UN authority; and a shift in public opinion in the UK, Europe and the Arab World.”

Many believe that Howard made a similar commitment to Bush during his June 2002 visit to Bush’s Crawford ranch. Howard’s own memoir, Lazarus Rising, certainly leaves the reader with that impression:

In our discussions during that visit, President Bush and I were careful to avoid specifics about Australian troop commitments to a possible invasion of Iraq. He knew that close discussions were under way between the US military and their Australian counterparts. He was entitled to assume on the basis of that, and also the tenor of our discussion, that if the military option was chosen by the United States then, in all likelihood, Australia would join. But he knew that I had not made any commitment to this effect and that for understandable political and other reasons I would keep my options open until the time when a final decision was needed.

Howard and Blair helped Bush create the Coalition of the Willing and engage in what former US secretary of state Madeleine Albright described as the “greatest disaster in American foreign policy… in terms of its unintended consequences and its reverberation throughout the region.”

The 2003 decision of the US-appointed head of Iraq’s Coalition Provisional Authority, L. Paul Bremer, to institute a de-Ba’athification program and dissolve the Iraqi army left disaffected Ba’athist military leaders to join with Islamists to create the precursor of Islamic State. The combination of religious fervour and strategic calculation has proven deadly for Iraqis now forced to live with shocking levels of violence and bloodshed. Estimates of Iraqi deaths as a result of the war vary between 150,000 and 382,000. Just this week, we have seen images of Baghdad residents picking through bombed sites for the charred remains of their relatives on the deadliest day since 2003.

Chilcot found that “the planning and preparations for Iraq after Saddam Hussein were wholly inadequate.” Blair was also warned that “attacking Iraq with cruise missiles would ‘act as a recruiting sergeant for a young generation throughout the Islamic and Arab world’” and that the “terrorist threat to Western interests would be heightened by military action against Iraq.” Despite these explicit warnings, he pushed ahead.

The inquiry found that “the assessed intelligence had not established beyond doubt either that Saddam Hussein had continued to produce chemical and biological weapons or that efforts to develop nuclear weapons continued.” At the time, Blair’s speeches argued for military intervention to address the “threat of chaos and disorder” arising from “tyrannical regimes with weapons of mass destruction and extreme terrorist groups” prepared to use them.

Chilcot’s findings echo those of the December 2003 report of the Australian Joint Parliamentary Committee on ASIO, ASIS and DSD chaired by government MP David Jull. It found that:

the case made by the government was that Iraq possessed WMD in large quantities and posed a grave and unacceptable threat to the region and the world, particularly as there was a danger that Iraq’s WMD might be passed to terrorist organisations. This is not the picture that emerges from an examination of all the assessments provided to the committee by Australia’s two analytical agencies.

The Jull committee detailed Australian intelligence agencies’ advice to the Howard government that made it clear there was no compelling case for war. According to the Defence Intelligence Organisation and the Office of National Assessments, Saddam Hussein “did not have nuclear weapons,” had “no known chemical weapons production,” and had conducted “no known biological weapons testing or evaluation since 1991.” At most, Saddam may have had some residual, ageing and depleted stocks of the chemical weapons he had used against the Kurds in Halabja in 1988. Under sanctions, said the ONA, “Iraq’s military capability remained limited and the country’s infrastructure was still in decline.”

Surprisingly, the fallout from Jull’s report was muted. It sparked media interest for just a couple of days, but failed to gain longer-term traction. On 2 March 2004, the day after the report’s public release, the Australian ran the headline “PM’s Spin Sexed-Up Iraq Threat” over a front-page article by their defence journalist, Patrick Walters. Howard announced a further inquiry, headed by former senior diplomat Philip Flood, and then went silent, starving the “sexing up” claim of oxygen. Inexplicably, Labor senator Robert Ray took the wind out of his own party’s sails when, in an interview with Tony Jones on ABC’s Lateline on 1 March 2004, he said that he did not believe the government had been deliberately misleading.

The lack of media interest may have had its roots in an incident two weeks earlier. In a clear breach of parliamentary privilege, sections of Jull’s draft report were leaked to a leading political journalist from the only major Australian daily that took an anti-war editorial position. The same media management strategy had been used in Britain to contain the media response to the Hutton inquiry into the death of scientist David Kelly. In this case, judging by the Sydney Morning Herald’s17 February 2004 front-page headline, “Case for War Not Sexed Up, MPs Find,” only those sections of the report favourable to the government appear to have been leaked. (Howard denied he had either leaked or authorised the leaking of the report.)

Deflecting attention away from the government, the leak framed the key issue in the Jull report as the divergence in advice between the two intelligence agencies, ONA and the Defence Intelligence Organisation, with the ONA “tend[ing] to produce material to fit with government policy objectives.” This framing of politicisation of the intelligence persisted for almost two weeks without contradiction and clearly influenced the public view, as well as other journalists’ reading of the Jull report when it was finally released. Several news organisations suggested that the report had cleared the government – which it had not. The “dead cat on the table” trick had worked.

Both Howard and Blair have accepted responsibility for their decisions to go to war but blamed flawed intelligence. In Howard’s case, his claim does not square with the advice of his own intelligence community, which failed to find a compelling case for the invasion. This detail was hidden in plain sight. Would another inquiry succeed in engaging our political elites in honest reflection where the Jull inquiry failed? •