We call a book good if it entertains or educates us. But when it deal with such a well-covered topic as “the glory that was Rome,” about which you could be excused for thinking there was little new to relate, it had better fulfil both functions or its intended readers will find better things to do with their time.

There was a time when Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire was regarded as the ne plus ultra of classical accounts but not even Francis Fukuyama suggested we had reached the end of history writing.

As Oxonian academic Ross King demonstrates in The Shortest History of Rome, there is always something up to the minute in a tale of ancient power plays provided it hews to the three Rs: relatability, reliability and revelation.

Expertly blending instruction with amusement, this fourteenth volume in the Shortest History series (the second authored by King after his study of Italy) presents serious lessons for our times and reminds us why the past should not be forgotten if a better future is what we desire.

But it’s also good for the odd chortle, which provides a necessary leavening amid the inevitable copious bloodletting. King usefully traces the customary arc of absolute rule. At first all goes well, the “first citizen” is showered with plaudits; then, as the author acidly euphemises, “Tiberius vigorously pruned the family tree.”

Without flinching from Nero’s depravity, King comes not just to praise Caesar but also — at this safe distance — occasionally to hold him up to ridicule. After ordering the construction of a large amphitheatre for plays and musical performances, Nero founded a Roman equivalent of the Olympic Games before competing in the original where, in 66 BCE, through “threats, bribes and Greek sycophancy, he won 1808 individual gold medals.” Best. Athlete. Ever.

An additional reason to read this new variation on old themes is to update what you thought you knew in light of revelations that explode a succession of myths long thought factual. Who founded the Eternal City? Not Romulus, raised with his brother Remus by a she-wolf. According to King, there are at least twenty-five versions of its foundation story. Cleopatra, according to Plutarch — but who among us knew? — used a poisoned hairpin to commit suicide, not a snake coiled in a basket of figs.

And, though the Goths of yore had the same dress sense as their modern eponyms, they weren’t the motive force behind the sack of Rome, but the slaves of the Huns, who had latterly ridden out of Central Asia, overpowered and press-ganged them into combat duty.

Which brings us to the latest explanation of what spawned the Hunnic exodus in the first place: climate change, namely “a series of major droughts and famines in central Asia”. At the turn of the fifth century, the “barbarian” hordes swarmed the empire’s eastern capital, Constantinople, and swept on into Eastern Europe, a humanitarian crisis that evolved into a famine there. It was nothing like a twenty-first-century American panic, though. When “desperate families sold their children into slavery for dog meat,” it was more a case of “the dogs are eating the people.”

Oh, and the Romans may have executed a scorched-earth policy after avenging Carthage in 146 BCE but they did not sow those fields with salt. That, we learn at last, is a modern legend with no factual basis. Fake news.

King wears his erudition lightly, in the style of a well-turned toga. Without neglecting the vivid instances and episodes you know are coming — Julius Caesar’s assassination, gladiatorial contests in the Colosseum and so on — he delves deeper, exploring both the processes that created Roman grandeur and those that reduced it to dust and ashes.

Like other successful imperialists before and since, the Romans would conquer another tribe, then colonise and absorb its culture, either partly or, in the unique case of the Greeks, whole. This was the fuel on which it grew until, under Hadrian in the second century, it extended all the way from Britannia to the Arabian Sea.

Sooner or later, the conquered — assimilated as Romans — would produce a ruler from their ranks. In the 500s BCE that was Tarquin the Proud, an Etruscan who became a power-hungry autocrat. Seven hundred years down the track it was Hadrian himself, from the province of Spain.

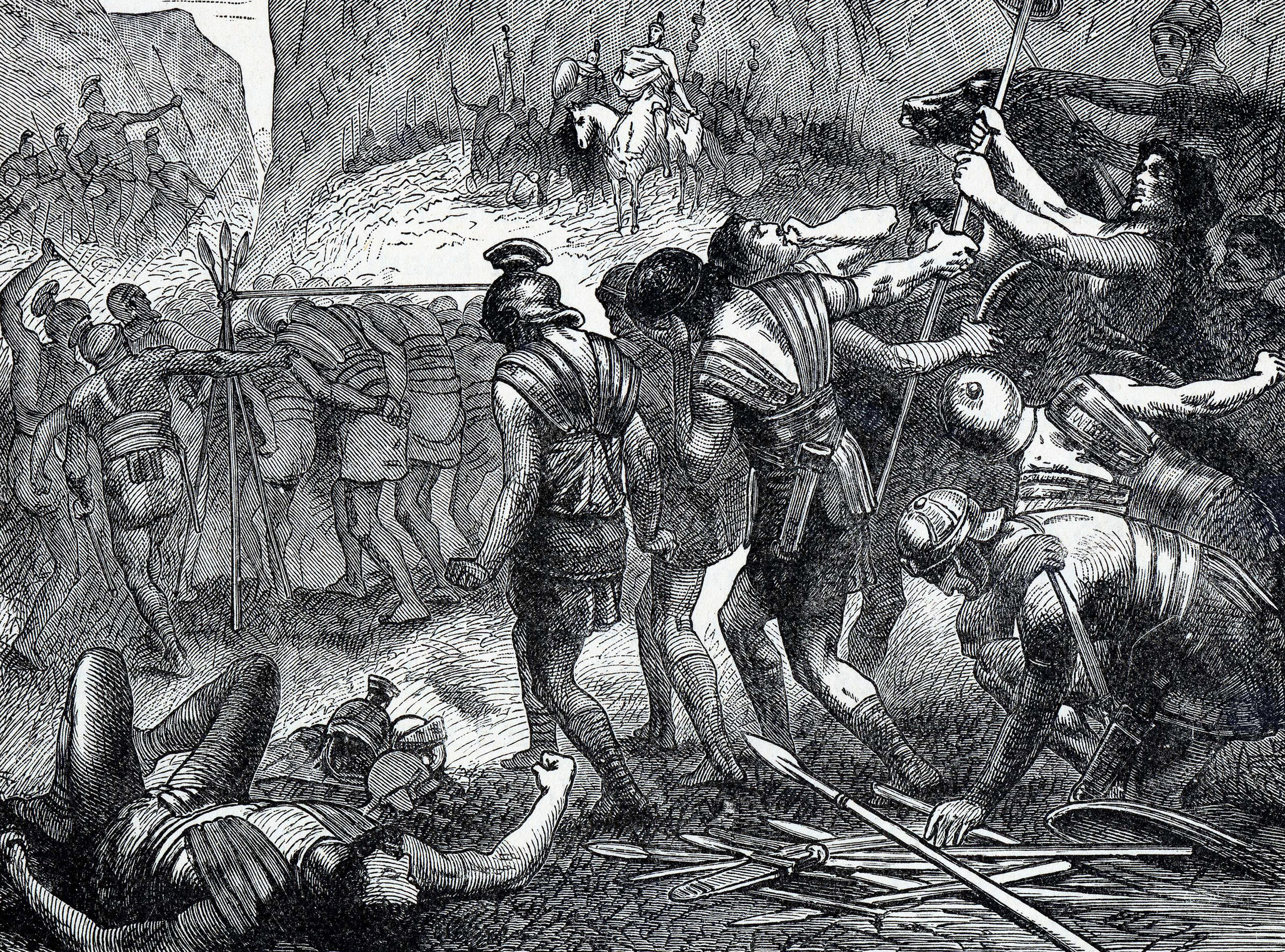

But it is the breadth of King’s knowledge, not its depth, that yields up shiny nuggets of information, revelations of things you never knew which make this book so special. Until reading him, this writer was sure that the highest single-day death toll in the history of warfare was the 19,000 British casualties on the first day of the battle of the Somme (1 July 1916). But that amounted to only a quarter the slaughter at Cannae, in August 216 BCE, when the Carthaginians under Hannibal routed the Romans.

In 12 BCE, a new landmark, the Theatre of Marcellus, boasted a retractable roof, rolled out to act as a collective sunshade; and twenty centuries before nations such as Australia did likewise, Rome legitimised same-sex marriage between men, complete with public rituals and legally binding contracts.

Arguably our major inheritance from Rome is something none of us can see, the language we speak. King states that 60 per cent of our vocabulary is derived from Latin (towards the upper end of a very large range: AI tells me it’s anything from 30 to 70 per cent). Whatever the macro-situation, he cannot be faulted on particulars.

To know that when the Samnite tribe trounced the Romans in the fourth century BCE Battle of Caudine Forks, they humiliated the defeated soldiers by forcing them to pass under a yoke (sub iugum) is to give our derived word subjugate mnemonic force.

Eight generations later, at Pompeii, Romans massacred 18,000 Samnites, a greater death toll than Vesuvius would exact two centuries on. (Ancient events often have modern application: those who marvel at the longevity of bloody rivalries in the Mideast and elsewhere may well conclude that history is little more than the outworking of long-held grudges.)

In the late third century BCE, King Pyrrhus of Epirus, on Greece’s Ionian coast, introduced the elephant to European warfare, using twenty of them, supported by 25,000 soldiers, to enable a Greek-speaking ally in Italy’s south to inflict a defeat on Roman arms. But the king’s forces sustained losses so great that Plutarch quotes him as saying, “If we are victorious in one more battle with the Romans, we shall be utterly ruined.” Thus was the template of “Pyrrhic victories” set for all time to come.

A shorter history, by definition, must omit certain facts, significant in themselves but not predominant in the author’s opinion. I would have liked to see it mentioned — as Stewart C. Easton did in his 1960s volume, A History of the Western World — that the term pontifex maximus, root of the English word pontiff for the Pope — originated with Caesar Augustus, who declared himself “the father of the nation” about seven centuries too late. But I suppose those who self-deify — he was “god,” by the way — also get to self-identify. One can only wonder about his choice of pronouns.

King mentions his self-compiled list of accomplishments, the Res Gestae divi Augusti (Achievements of the Divine Augustus) and emphasises his mock humility — professing no more power than that of princeps (first citizen) while admitting; “I excelled all in influence, although I possessed no more official powers than others who were my colleagues in the various magistracies.”

With a rare lapse into naivety, King says August respected the Senate. Fellow Oxford historian Robin Lane Fox, writing twenty years ago in The Classical World, was more sceptical, describing how the Emperor wheedled senators into appointing him consul for the majority of provinces, notably Gaul, Spain and Syria. Even in those days it didn’t do call oneself a dictator for too many days, so a forty-one-year reign began with his agreeing to govern “for up to ten years.”

Rightly, King debunks Gibbon’s thesis ascribing the empire’s decline and fall to Constantine’s adoption of Christianity. He quotes a modern German historian who has found 210 reasons for the collapse of Rome, rather draining the word “cause” of all sensible meaning.

King, it ought to be said, does a fair imitation of Janus. Far from conducting a route march through centuries of carnage, he displays both the auspicious and atrocious faces of Roman rule.

Julius Caesar’s introduction of the solar year of 365 days, with a quadrennial tweak, is duly noted. The century-long era of the “five good emperors” beginning with Trajan and ending with Marcus Aurelius is celebrated. Like the citizens of those days made cynical by corrupt glory-seeking egotists, we need reminding of a simple truth much scoffed at: government can do good. Historian Pliny the Younger praised Trajan’s humility, politeness and compassion which, he informs us, elicited warmth and happiness rather than animosity and fear.

Dictators tend to acquire an aureole of benevolence once enough centuries have passed. Decades after they died, Hitler and Stalin remain recognisable villains, at least in the West. But to see Caesar or even Napoleon as a source of terror for millions is hard to imagine at this safe remove. Yet the aura of the “strongman,” the putative saviour who “selflessly” offers to fix all of society’s ills — continues to beguile.

King does well to remind us of what a populist in action looks like. In the Gallic Wars (on battlegrounds that map right over those of the Western Front) Julius Caesar “conquered or set fire to 800 cities and towns, subdued 300 tribes… and killed (by Plutarch’s reckoning) a million people, enslaving perhaps as many more.”

And so we can answer with confidence that more than rhetorical question: apart from tutoring posterity in political wisdom (and folly), history, semantics, calendrical reform, public baths, sanitation, education, medicine and, not forgetting, the aqueduct, what have the Romans done for us? Well, in their bloody rise and civilised heyday as much as in ruins, as Ross King demonstrates in 65,000 well-chosen words, they taught us once and for all that no superpower — not even the greatest (Russia, China or America, if you’re listening) — lasts forever.

Unsurprisingly, the Latins had a word or three for that as well: Sic transit gloria. •

The Shortest History of Rome

By Ross King | Black Inc. | $27.99 | 272 pages