Dotter of Her Father’s Eyes

By Mary M. Talbot & Bryan Talbot | Jonathan Cape | $39.95

THE life of the author of Ulysses is as enticing as the Homeric saga on which it is based, and both continue to keep professors very busy. The distinguished literary critic Hugh Kenner was famously impatient with the myopic attention given to James Joyce’s life – so much so that he snubbed Richard Ellmann’s revised biography in 1982 as exhibiting the “impertinence of being definitive.” But despite the hagiography surrounding him – even, from the likes of Scott Fitzgerald and Ernest Hemingway, during his lifetime – Joyce himself believed in the classicism of the Odyssey as a drama of fundamental human experience. In Ulysses, he reflected his own life as father and husband in Leopold Bloom, struggling advertising hack and wannabe conscience of his own race. Bloom was an odd figure, displaced in a world that underlined his fundamental ordinariness, and just as his experience is like Odysseus’s, Joyce’s relationship with his daughter Lucia, warts and all, is representative of any father’s bond with his daughter. This is the premise of Dotter of Her Father’s Eyes.

The parallels between being the daughter of James Joyce and being the daughter of an eminent Joyce scholar form the basis of this graphic novel. Dotter of Her Father’s Eyes seeks to explore the contrast between the doting affection of the father of one squinty daughter and the indifference and casual anger of another. James Atherton’s The Books at the Wake (1959) was not the first attempt to document the weight of literary allusion in Finnegans Wake, but it was certainly the most comprehensive and authoritative. And it is the discipline and aloofness required to write such a book that partly explains the fraught and at times turbulent relationship between Atherton and his daughter, Mary Talbot.

Unlike that other graphic novel, Joyce’s notorious “blue book of Eccles,” Dotter of Her Father’s Eyes is motivated by little except one father’s obsession with another’s writing and the emotional fallout this entails for his family, and particularly for his “dotter.” The intersecting lives of the Joyces of Paris and the Athertons of Wigan counterpoint the bohemian moveable feast of one family and the dark postwar days of another. And if this is not enough for a family to deal with, the fixation with chasing down textual allusion in the most notoriously difficult book in English sets the mise en scène for a family romance that would have undoubtedly detained the attention of Freud.

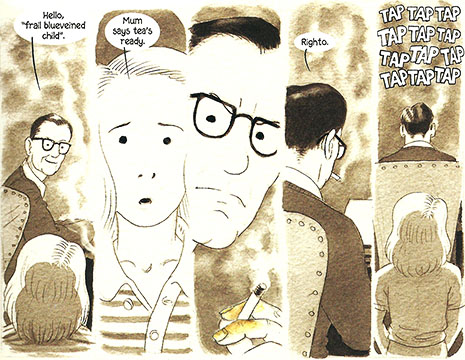

But the contrasts and contradictions are profound. Nora Joyce famously told Jim to stop writing or stop laughing during the ferocious scribbling of Finnegans Wake, a moment of gentle censure that reflected the author’s mood during the seventeen-year stint of its composition. James Atherton is portrayed as a chain-smoking workaholic writing about the writing of someone else, a man whose mood would swing from loving dad, cajoling Mary with Joycean punmanship (“What kind of a noise annoys an oyster?”), to an indifferent and often ferocious “feary father.” When he is not TAP-TAP-TAP-tapping on the typewriter, Atherton is most frequently rendered with mouth wide open shouting at his daughter. Given to slamming the door of his study in her face and occasionally tanning her behind, he is far from benevolent and loving. Hyper-conscious of this fact, Mary admits at one decisive moment that “I started hearing sarcasm when he smiled.”

Talbot repeatedly makes the point that the obsessive solitude of writing can compromise the relationship between one family member and another, and particularly between father and daughter. She makes it very clear that her relationship with her father is nothing like Joyce and Lucia’s. But family drama aside, this book doesn’t manage to establish the need for a graphic treatment of the specific situation of Atherton’s obsession with Finnegans Wake. There is something decidedly bookish about the petulant, myopic author fixated on literary minutiae in a monochrome and parsimonious England. It is too grounded in one young woman’s quite specific experience of the writerly sins of the father to have an appeal beyond Joyceans with a similar interest in the behind-the-scenes dramaturgy of literary biography.

By way of contrast, illustrators like Martin Rowson have made a fine art of the graphic treatment of classic novels, such as his sublime Tristram Shandy (1996), in which the cramped, fast and satirical visual style helps bring that peripatetic and loquacious text to baroque life. It is neither appropriate nor fair to compare Bryan Talbot’s vernacular hand-drawn style to Rowson’s Augustan pomp, but the main point of the comparison is to highlight the latter’s visual retelling of a familiar story. Joycean arcana may not be the most likely motivation for a coming-of-age story of two young girls – except, of course, unless one is Lucia Joyce and the other the daughter of a Joyce scholar. But for the general reader a book about the writing of The Books at the Wake is likely to be as esoteric as the Buddhist references that Stuart Gilbert identified in his 1930 study of Ulysses or the number of incidences of the definite article (14,877) that Miles Hanley collated in his 1937 Word Index to the same text.

Other para-texts along the lines of Dotter of Her Father’s Eyes have sought to explore the intricacies of Joyce’s complex relationship with those close to him. Like a salacious potboiler, Stan Gébler Davies’s A Portrait of the Artist (1975) wants to tell us what really happened when Jim and Nora went out walking for the first time and she granted him “probably the first momentous sexual favour he had not paid for.” Another, Mairéad Byrne’s Joyce: A Clew (1981), juxtaposes a series of epigrammatic reflections on the various phases of Joyce’s movements through the Continent with stylised illustrations by Henry Sharpe that render these biographical vignettes in appropriate visual styles of the time. In one such image Joyce’s elongated shadow, sampled from de Chirico, encroaches on a distracted visage of Lucia (an economical and striking totem of the long reach of the father that Talbot is at pains to draw out in her parallel father-daughter narrative).

Other works have treated Joyce’s characters as postmodern avatars of the imaginary becoming so intimate that we forget they are not real. Peter Costello’s Leopold Bloom: A Biography (1981) is an inventive treatment of Bloom’s life as if it had been written by someone as rigorous as Richard Ellmann. But in this instance it is not biography but fiction that provides Costello with a wealth of information about the Jewish advertising canvasser’s thoughts, life and opinions. Costello has a wealth of detail to work with in the fractal-like information about Bloom to be gleaned from the pages of Ulysses. But the conceit of Costello’s biography is to imagine and indeed create “the ‘other’ post-1904 Bloom, the man of whom Joyce says nothing.” Such is Costello’s attention to this Borges-like irrealism that a note appended to the dustjacket of the book explains the provenance of its cover illustration: “from an etching entitled ‘The Only Remaining Authentic Photograph of Leopold Bloom Taken on Wellington Quay June 16, 1904 and Discovered by Gerald Davis in December 1979.’”

On the back cover of Dotter of Her Father’s Eyes one reviewer emphatically asserts that this “is one of the best collaborative efforts I’ve seen in the comics medium.” I beg to differ, especially in terms of the Joycean connection. In 1995, the underground grunge comic Tank Girl published four issues subtitled “The Odyssey” (DC Comics). Loosely modelled on Homer, this series frequently gestures to Ulysses and on more than one occasion quotes directly from it. It was the most startling and least expected context in which to encounter the opening words from the “Oxen of the Sun” episode: “Deshil Holles Eamus. Deshil Holles Eamus. Deshil Holles Eamus.” The anarchy of Tank Girl colliding with Homer and Joyce in this way is a sublimely punk moment of transgression that only makes sense visually. As fascinating, melancholy and occasionally joyous as Talbott’s story is, Dotter of Her Father’s Eyes does not. •