“I will save my version for my memoirs,” declared Malcolm Turnbull. It was 2006, and he was talking to Age business editor Michael Short about an article I had written for the next day’s paper. There, I outlined for the first time Turnbull’s pivotal role in sinking Kerry Packer’s bid to control the Fairfax newspapers.

Nearly thirty years later, Turnbull has published those memoirs, A Bigger Picture, but readers will look in vain for the most salient and salacious details of that extraordinary episode. Why, I wonder, has Turnbull skated so lightly over the acrimonious climax of his relationship with Packer?

The key events unfolded in late 1991, at the tail-end of the most turbulent period of media ownership in Australian history. The upheaval had begun with the Hawke government’s changes to media ownership rules in 1987–88. The new policy, devised by Paul Keating, prohibited a company owning both a newspaper and a TV channel in the same market and abolished the old two-station rule, thus allowing one network to own channels reaching up to two-thirds of the Australian population.

The new policy advantaged Packer (who owned no newspapers) and Murdoch (who, having become an American citizen, would have had to sell his Australian TV stations anyway) and disadvantaged the other two big groups — Fairfax and the Herald and Weekly Times — whose cross-holdings of media outlets made any expansion almost impossible. It was later revealed that, of the four, only Murdoch and Packer had been consulted beforehand.

The new policy led to a frenzy of acquisitions, with many cashed-up aspirants seeing this as the last chance to buy into television. Alan Bond bought the Nine network from Packer for a billion dollars (twice what it was worth, writes Turnbull). Frank Lowy bought the Ten network and Christopher Skase bought the Seven network, both at greatly inflated prices.

Rupert Murdoch saw his opportunity, and took over the Herald and Weekly Times. After a shake-out of its various properties, this left him in control of newspapers accounting for two-thirds of daily metropolitan circulation, a much greater degree of concentration than in any other democracy.

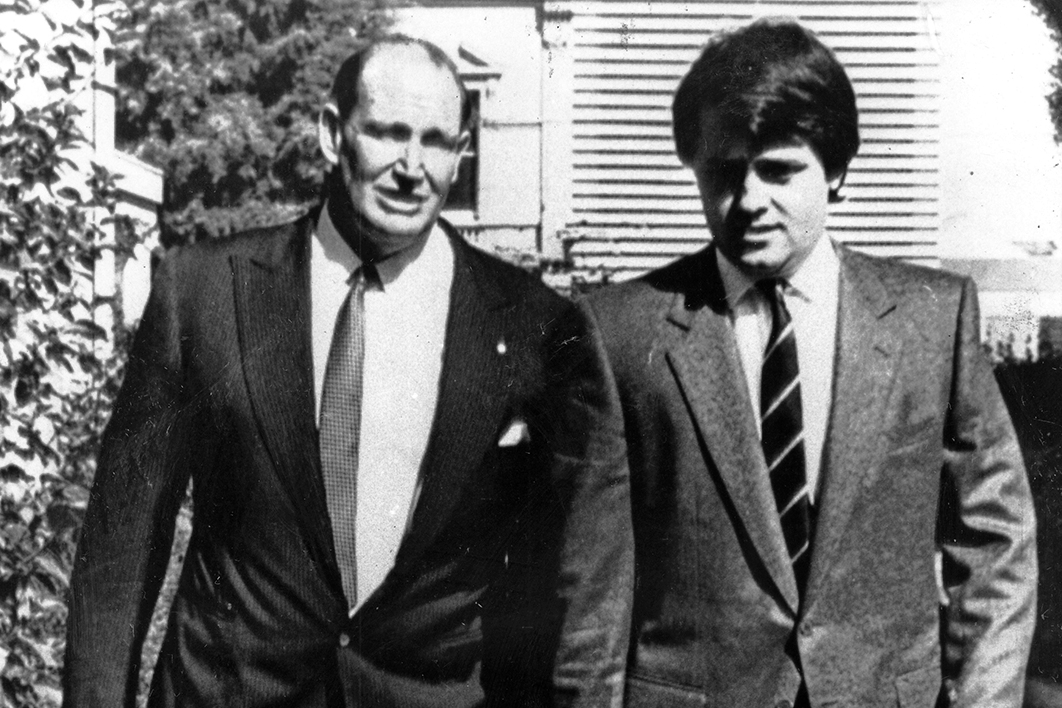

The most irrational of the ownership moves owed more to family fantasies than financial calculation. Egged on by a group of shady characters, Warwick Fairfax — know universally as Young Warwick, to distinguish him from his famed father — privatised the company, buying out his relatives and other shareholders, and accumulating enormous debt in the process.

The ownership changes transformed the media landscape. The nineteen metropolitan newspapers were reduced to eleven after all the afternoon titles closed. Twelve hundred journalistic jobs were lost, with commercial TV staff numbers peaking in 1988 at 7745 and declining, three years later, to 6316. Within three years all the new TV network owners had left the industry under mountains of debt.

The architect of the scheme, Paul Keating, was unrepentant. The result, he thought, was “what I think is a beautiful position compared with what we did have.”

Turnbull was involved more closely in more of these deals during those years than any other person. He helped Packer sell Nine to Bond and, later, to buy it back. He sought to help Warwick Fairfax deal with his debt problems, and later tried to help him sell the Age to Robert Maxwell. He acted for Westpac when it put the Ten network into receivership, with the bank acquiring ownership for a few years before onselling it to CanWest.

Turnbull’s chapter about these events in A Bigger Picture, “Moguls, Madness and the Media,” is a rousing recital of triumphs and frustrations. Missing, though, is any hint that he saw any public interest dimension to this wheeling and dealing.

The most dubious transaction was Westpac’s takeover of the Ten Network. After its owner, Frank Lowy, had become disillusioned with television, he had sold a fifth share of the network to Steve Cosser’s Broadcom, which took over day-to-day management. Ten showed signs of a revival but was still losing money at a dramatic rate. Turnbull, acting for Westpac, forced the company into receivership, and ousted Cosser in September 1990. The new management, headed by former Nine executive Gary Rice, set out to “radically cut costs,” in Turnbull’s words, with the goal of being “the most profitable television station, not the top-rating one.”

Other options didn’t seem to be welcome. When ad-man John Singleton started to put together a group to make a bid, he received “the angriest phone call of my life from Turnbull,” as he later told journalist Roy Masters, even though Westpac would have been expected to welcome a bidding process.

Rugby League games were the station’s most consistently high-rating programs. The new management’s first move was to renege on a payment it was about to make for broadcast rights. When Ten then said it would pay $4 million rather than the agreed $16 million a year, Rugby League took back the rights. In the new auction, Nine acquired them for $6.5 million, offloading various fixtures including club matches back to Ten for $7.7 million — thus making an immediate profit while keeping the most profitable parts, such as State of Origin, for itself. As Paul Barry wrote, it was “a remarkable deal for Packer and a disaster for Ten.”

Ten’s cuts affected its programming so greatly that some commentators took to saying that Australia’s old structure of three commercial networks had become a two-and-a-half network system. By 1991 Nine employed ninety-five journalists in Melbourne and Sydney, but Ten had only twenty-nine. Nine spent $49.3 million on news and current affairs, Ten just $15.1 million.

Not surprisingly, Ten’s audience share declined from 29 per cent in 1988 to 21 per cent in 1991 in Sydney; and from 30 per cent to 20 per cent in Melbourne. The other networks sought to take advantage, with the Financial Review reporting that “Networks Nine and Seven are trying to persuade the country’s advertisers that Network Ten is a spent force to justify rate increases of up to 14 per cent.”

Cosser charged that Turnbull, who had been a member of the Nine board until he resigned to work on Westpac’s move on Ten, was an agent for Packer. Turnbull vehemently denied this. But if he had been Packer’s agent it is hard to imagine what he would have done differently.

Although the Ten changes had profound public interest implications and attracted considerable attention in the business pages, they passed almost unnoticed in the general media. By contrast, the prospect that Packer might gain control of Fairfax provoked a more widespread and stronger public response than almost any other issue in Australian media history.

Warwick Fairfax’s folly climaxed with the company being put into liquidation in December 1990, ending the almost 150-year relationship between the family and the Sydney Morning Herald. The company’s receivers set about trying to get the best price for the company.

Packer, meanwhile, was at the apogee of his power. According to Turnbull, he had bought back control of Nine for about a third of what he’d sold the network for. And with the other two networks in the hands of receivers, his was the only cashed-up commercial broadcaster.

Now he set his sights on Fairfax. Because of the cross-media laws — from which he had profited more than anyone else — he could only own up to 15 per cent and could not exercise “control.” With that in mind, he formed the Tourang syndicate to mount the bid. The idea was that Packer would own just under 15 per cent, Canadian press baron Conrad Black 20 per cent and the American hedge fund Hellman and Friedman 15 per cent, with the rest floated on the stock exchange. Among the several other bidders, the early favourite was the Irish food and media magnate Tony O’Reilly.

Showing great entrepreneurial agility, Turnbull became the agent for the American “junk bond” holders. Junk bonds are issued by embattled companies to raise needed capital, but because the companies already have significant outstanding debts they need to promise higher returns to compensate for the risk involved. Fairfax had — probably foolishly — engaged in such capital raising the previous year. To emphasise the pivotal role of these bond holders, Turnbull launched an action against Fairfax on their behalf for $450 million, charging that they had been deceived when they made their investment. Looking for a partner for the junk bond holders, he soon teamed up with Tourang.

As the months passed, opposition to further media concentration — and especially to Packer — mounted. Gough Whitlam and Malcolm Fraser, who had barely spoken to each other since the momentous constitutional crisis of 1975, shared a political platform for the first time. A dozen prominent ex-politicians, including Fraser and Whitlam, signed a letter about the threat of media concentration; though they didn’t name Packer, their target was clear. A bipartisan petition gathered 128 of the 224 MPs’ signatures in a matter of hours. Public rallies attracted thousands. A new group, the Friends of Fairfax, attracted strong support among journalists. It was becoming harder for the Hawke government to ignore the reaction.

Publicly, Packer maintained that he would simply be a minor shareholder, with just 14.99 per cent of the company, and would in no sense control the company. Interviewed on Nine, he declared that “for fifty years of my life, Fairfax has been competition to me and my family. The idea that I can end up buying 15 per cent… amuses me.” Much more immediately successful was Packer’s appearance before a House of Representatives committee, where he bullied MPs and refused to respond to awkward lines of inquiry.

But concern was growing inside Tourang. If its bid succeeded, Fairfax’s new chief executive would be Trevor Kennedy, who had been a Packer employee for almost twenty years. Packer had been spending increasing amounts of time with the representatives of the two overseas companies — Daniel Colson (a solicitor for Conrad Black) and Brian Powers (from Hellman and Friedman) — who were helping manage the bid in Sydney.

Colson and Powers thought that Kennedy’s involvement was a political problem because he was seen as Packer’s man, and accused him of not pulling his weight in the takeover team. Eventually, in mid October, Kennedy resigned. His public statement blamed the “McCarthyist” campaign against Packer, but in truth he had been forced out by the other parties to the bid, and he particularly resented Packer’s lack of support.

A month later Colson and Powers moved against Turnbull. According to Conrad Black, “a number of the banks didn’t wish to deal with him. And he rather severely aggravated some of the other participants.” Turnbull was enraged that Packer wouldn’t take his calls. Of course, Turnbull didn’t depart as meekly as Kennedy had.

The Tourang partners demanded Turnbull’s resignation on Friday 23 November. Talks went on over the weekend, and media interest intensified. The crunch moment arrived on Sunday.

As I wrote in the Age in 2006, and repeated in a Four Corners program in 2008, Turnbull met with the head of the Australian Broadcasting Tribunal, Peter Westerway, in the early evening on a street in Kirribilli. Westerway, a former Labor Party official who had worked in the TV industry, had announced an inquiry into the takeover a few weeks after Packer’s parliamentary performance. Sitting in Westerway’s car, Turnbull handed over documents about the Tourang bid.

All that Westerway ever said publicly was that a public figure known to him had telephoned him earlier in the day. His source told him that “he, his wife and family were all at risk,” and Westerway judged that “he had a genuine apprehension.” Later he said the source wasn’t Kennedy.

The most important of the documents Turnbull leaked to Westerway were notes made by Kennedy, especially those made immediately after he had been forced out. They showed Packer planning to be far more involved in running Fairfax than he had admitted. When he told the parliamentary committee he had no plans for controlling Fairfax, he challenged them to either “believe me or call me a liar.” In fact, he was lying. If Kennedy’s notes had become public, they would have skewered the bid.

On 26 November, about three weeks after Packer appeared, Westerway told the same parliamentary committee, without elaborating, that he was initiating an inquiry into the Tourang bid. The tribunal immediately sought papers from the participants, the specificity of its request indicating it knew exactly what to ask for. Kennedy’s notes would show that Packer exercised and intended to exercise much more influence than had been admitted. Westerway now sought to obtain officially what he already knew unofficially.

Two days after Westerway’s announcement, Packer sensationally withdrew from the bid. Later, in a revealing choice of words, he accused Kennedy and Turnbull of “treason.”

The Labor government duly punished Westerway for enforcing the law. Very senior figures in the government had told him that he would head the tribunal’s looming replacement, the Australian Broadcasting Authority. Now they told him that Graham Richardson had vetoed his appointment, and former journalist and high-profile publisher Brian Johns would get the job instead. (Some years later, with me as his supervisor, Westerway wrote a PhD thesis on Aboriginal broadcasting, which he had been very involved in promoting in its early days. He graduated in his mid seventies, and died, aged eighty-four, in 2015.)

Within a couple of days in December, the Tourang bid, minus Packer, was approved by the government and Keating replaced Hawke as prime minister. The new government’s eagerness to please Packer was undiminished. One of Keating’s first actions was to appoint Richardson, nicknamed the “minister for Channel Nine” in Canberra, as transport and communications minister. Over the following years the government turned somersaults on pay TV policy to please the mogul. In return, Packer endorsed John Howard as prime ministerial material as soon as he sensed a shift in the political wind.

When Four Corners covered these events in 2008 it elicited a confirmation of the basic facts from Turnbull, who stressed that he had emerged victorious. Later he gave Annabel Crabb a more expansive account of his dealings with Packer. “Kerry got a bit out of control at that time,” he said. “He told me he’d kill me, yeah. I didn’t think he was completely serious, but I didn’t think he was entirely joking either. Look, he could be pretty scary.” Warming to his theme, he went on: “He did threaten to kill me. And I said to him, ‘Well. You better make sure that your assassin gets me first because if he misses, you better know I won’t miss you.’ He could be a complete pig you know… But the one thing with bullies is that you should never flinch.” He had leaked the documents, he told Crabb, to teach Packer a lesson.

Why, then, is the account in Turnbull’s memoirs so truncated and unsatisfactory? It is not that he thought the episode was unimportant. Indeed, his chapter finishes by recalling “one of the sweetest moments in my corporate life.” At the settlement of the Tourang takeover he picked up his bank cheque and as he turned to leave, the “room seemed very quiet,” except for “the soft sound of the grinding of teeth.”

In a revealing interview last month, David Crowe asked him why about his account of the episode was so sparse. Initially Turnbull replied, “A lot of this is lost in the mist of time. I had a discussion with Westerway at the time but I don’t believe I gave him the Trevor diaries.” This defies belief: giving Kennedy’s notes to Westerway was the central act on which everything else hung. But then Turnbull added a more honest and interesting response: “Anyway, the bottom line is what I said to Annabel related to some threats Kerry made against me, which I deeply regretted having recounted and I resolved I wouldn’t repeat.”

Why such regret? The whole episode doesn’t present Turnbull in a bad light. But it does show Packer to have been a liar with an inflated sense of entitlement who thought he could bully his way to success and showed no loyalty to two people who had given him such long service. So does Turnbull’s reticence reflect regret over his lost friendship with Packer? Is it that his long closeness to Packer means he wants to protect Packer’s reputation in case Packer’s misdeeds reflect back on him?

Turnbull’s memoirs do offer one new anecdote about Packer. He had agreed that Turnbull would receive a $3.5 million success fee after Packer regained control of the Nine network. Instead, Turnbull received a cheque for $3.4 million. He rang Trevor Kennedy to ask why.

“He just wanted to give you a little haircut,” Kennedy replied.

“Why?” asked Turnbull.

“Because he can.” •