Darren Rix and Craig Cormick’s Warra Warra Wai has a very long subtitle: How Indigenous Australians Discovered Captain Cook & What They Tell About the Coming of the Ghost People. And this is precisely what the book does. The authors describe how they followed the journey of Cook’s Endeavour up the east coast of Australia, putting back the original names of all the landmarks renamed by Cook and recording the stories the First Nations people at those sites wanted to share. These stories are supported by archival research into the often harrowing history of dispossession and genocide in those localities.

The book is a rivetting read — you can do it in a day — but elusive to review. When I sat down to write I found myself procrastinating, reading incoming emails. I found inspiration in a review newly published on Inside Story: Peter Marks writing about Dennis Glover’s Repeat; A Warning from History. Glover, he says, “wants readers to become historically informed, motivated political actors… he implores us not just to think, but to ‘do something.’”

I was reminded of the words of Thomas Holden of the Gooreng Gooreng mob at Gooragang, Bustard Bay, in response to the question Rix and Cormick asked of all their informants: “What do you want whitefellas to know most about your mob?”

Holden replied: “We want their minds to open up to walk with us… The invitation is there. People just don’t know how to do it. So, go to an event. Invite an Aboriginal person into your home. Listen to where we want to go to. Invest in people’s business, walk with us, anything.

“Anything.”

Like Glover’s Repeat, Warra Warra Wai is a polemic that seeks to create historically informed actors. Its understanding of “history” is broad, giving family memories the same interpretative value as documented “facts.” In the wake of the failure of the Voice referendum readers are asked to open their minds to the understandings First Nations people have of their past, and their hopes for the future. They are also asked to act.

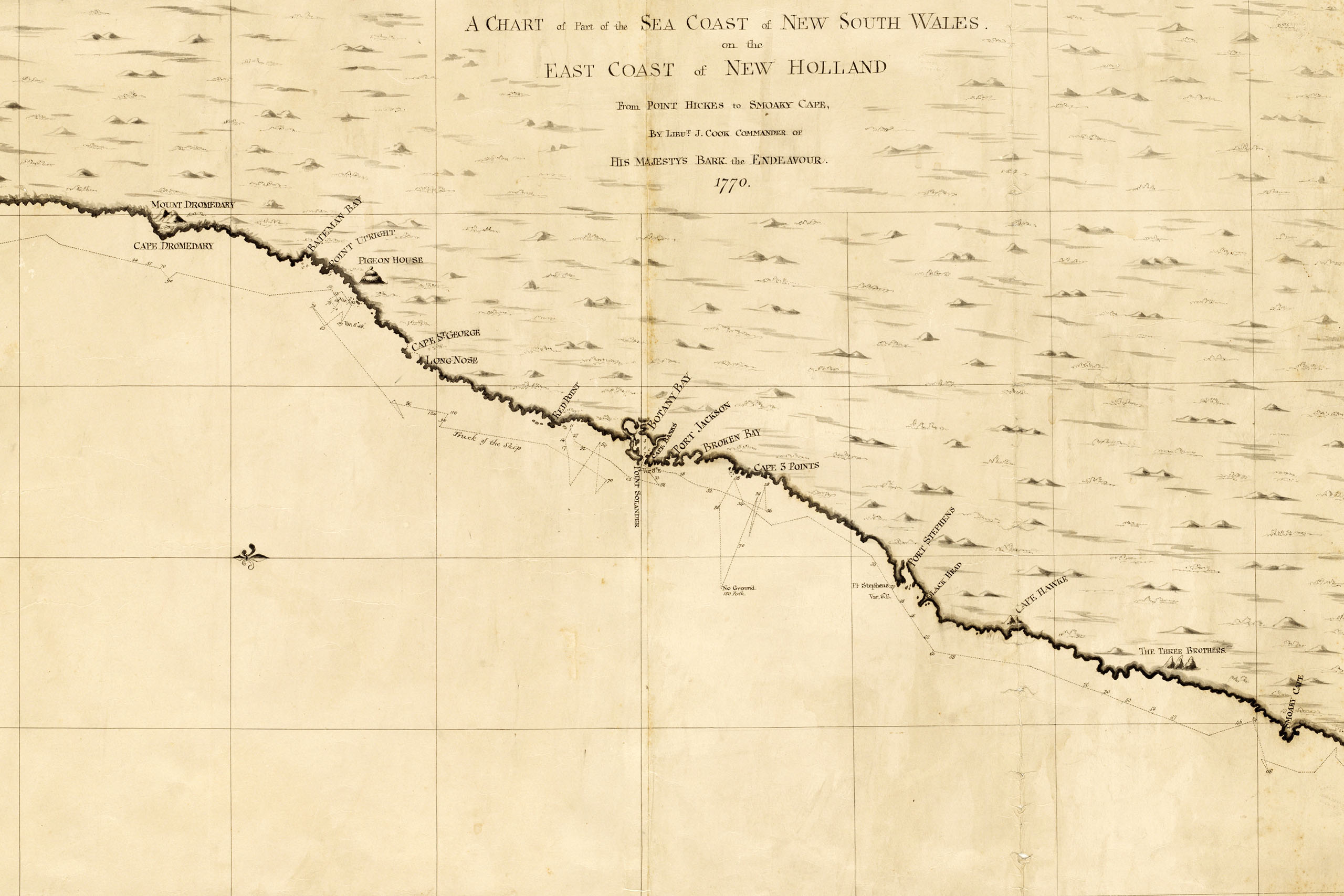

The book is shaped by place and community. Each chapter tells the story of a locality or a landmark renamed by Cook: stories of its creation by Dreaming ancestors, of the long years of Indigenous life there before European invasion, of mostly violent dispossession. An early chapter tells how the double-peaked mountain renamed Mount Dromedary by Cook was Gulaga to the Yuin people, “their sacred mother mountain.” “Where Cook saw a camel sitting down,” they write, “the Yuin people see a pregnant woman lying down, her head to the south, her feet to the north, facing the sea.”

Across nine different seasons marked by different foods, the sea and the land sustained the Yuin, and their elders taught the children to protect the land’s resources. First contact with the white invaders was peaceful, but when sealers provoked violence by stealing Yuin women they were met with brutal retaliation. Today the Yuin language, Dhurga, is being revived, and there is a resurgence of dance and culture. Tourists come to climb Gulaga, though members of the local Yuin community would like to prevent this.

There is strength in this localised structure, and perhaps weakness. My ancestral place is the mid-north of South Australia, the lands of the Nukunu and the Kaurna people. I am not at all familiar with the peoples and the landscapes of the east coast, and I struggled to locate their stories. I compensated by reading with Google maps open on my iPad beside me. I was able to find all of Cook’s landmarks, often with photos of the sites and the surrounding landscape. Without this digital assistance Warra Warra Wai would have meant much less to me.

The impact of Warra Warra Wai will clearly be strongest for people reading about their own localities. Readers who can see Mount Dromedary from their kitchen windows and recognise the pregnant mother Gulaga will be more readily moved to act than readers in the suburbs of Melbourne or Adelaide. But this is a national story, and for any reader its moral is inescapable. We the invaders must listen to the voices of First Nations people, walk with them, and not stand in their way. •

Warra Warra Wai: How Indigenous Australians Discovered Captain Cook & What They Tell About the Coming of the Ghost People

By Darren Rix and Craig Cormick | Scribner Australia | $34.99 | 352 pages