“Woman Shows Pictures” was the headline of Melbourne’s Weekly Times review of an art exhibition in 1949. Whether the words were chosen to express disapproval or simple wonderment, the meaning was clear. When a woman put her paintings on public display you had to ask: who did she think she was?

This rulebreaker was Constance Stokes. Although she won the coveted two-year National Gallery travelling scholarship in 1929, she never received the same recognition in Australia as her male competitors. Exhibiting in London, she won high praise from Kenneth Clark and other British critics, but at home she was largely ignored. Forgotten for many years, Stokes is only now being rediscovered.

She wasn’t the first woman to show her work in public, of course. Women had been exhibiting their paintings in Melbourne and elsewhere for decades. But they didn’t have the assurance of male artists; and when they exhibited in the company of men, their work was often ignored. Many careers paused because of the demands of marriage and children, as did that of Constance Stokes. Some never developed.

Women’s individual achievements were belittled. When Nora Heysen won the Archibald Prize for portraiture in 1938, she was photographed in her kitchen. The report was headed: “Girl Painter Who Won Art Prize Is Also Good Cook.” Heysen was twenty-eight years old. An unsuccessful entrant, Max Meldrum went public with the thought that it was “sheer lunacy” for women to think they could paint as well as men. Being “differently constituted,” they should concentrate on raising a healthy family.

Meldrum was echoing the long-established view of the proper role of female artists. Samuel Johnson gave his ruling in the mid eighteenth century when he declared that “public practice of any art [was] very indelicate in a female.” When portrait painting involved “staring in men’s faces,” it was a serious breach of decorum.

Such comments were not about a woman’s skill as an artist; they were about her place in the world. If she insisted on devoting her time to painting, she would do best to stick to flowers or small children, and not to offer her work for sale. In some ways, it was easier for female writers. They could make themselves invisible, as Jane Austen did when she published as “A Lady,” or, like the Brontës and George Eliot, they could use a male pseudonym.

Nora Heysen’s Archibald win might have been less offensive to traditionalists because her subject was a woman, the elegant wife of the consul for the Netherlands. In 1960, when Judy Cassab won the award with a portrait of the swaggeringly assertive Stanislav Rapotec, the press wanted to be sure that Cassab could cook and was a devoted mother. By winning the prize for a portrait with a male subject, she made a double breakthrough. Cassab won again in 1967, this time with a female sitter. Other female artists had to wait. Over the hundred years of Archibald contests, only eleven women have taken out the prize.

Questions about a woman’s place in the public world of art are central to Jennifer Higgie’s new book, The Mirror and the Palette: Rebellion, Revolution and Resilience: 500 Years of Women’s Self-Portraits, a captivating study of how female artists have created their images of self. Although the invention of the mirror benefited male as well as female painters, it had special meaning for women. Excluded from the life class, they could become their own models.

In earlier times, the female self-portrait had often come from those whose artist fathers trained them to be studio assistants. The remarkable seventeenth-century artist Artemisia Gentileschi was taught by her painter father, who in turn was a disciple of Caravaggio.

Until the nineteenth century, mirrors were scarce and expensive. But the female self-portrait flourished as soon as any female artist could study her own likeness. She saved money by not employing a model, and she could be alone with her art. It wasn’t just a matter of making up for the life class in a private anatomy lesson; for many, it was a chance for reflection.

Alice Neel in front of her 1980 self-portrait in New York. Sonia Moskowitz/IMAGES/Getty Images

Higgie adroitly places her artists in the context of their times and personal circumstances. Rather than take them in chronological order, she uses a thematic structure that groups them under such headings as “Smile,” “Allegory,” “Hallucination” and “Naked.” The “Smile” chapter is really about not smiling; the Mona Lisa look is as open as it gets. Some of the women depicted are lively and responsive to being seen, but they seldom show more than a glimpse of teeth. This restraint, as the author suggests, may have been partly due to poor or non-existent dentistry, but even in modern times the lips of most sitters remain closed.

The naked self-portraits were created in deliberate defiance of the rules that for centuries excluded women from the life class. In 1980, American portraitist Alice Neel painted herself at eighty, with no soft lighting on her ageing body. Unfazed by showing her sagging breasts, she faces the world with assurance, her expression jaunty. No regrets, no apologies; this is who I am.

In “Allegory,” the author suggests, we find coded messages from the painter. The empathy for the terrified woman in Artemisia Gentileschi’s Susanna and the Elders (1610) must reflect the artist’s own experience as a victim of rape. In 1794, a middle-aged Angelica Kauffmann looked back on her choice of career to paint herself in a moment of hesitation between the competing arts of music and painting. Angelica, an innocent in white, rejects the advances of blowzy Music and begins the uphill climb marked out for her by the stern figure of Painting.

“Hallucination” includes the wayward art of Leonora Carrington and the nightmare visions of Frida Kahlo. Carrington’s self-portrait shows the artist seated on a red cushion in an empty room. Behind her is a white rocking horse; outside the window another white horse gallops freely. Close to the artist’s chair, a hyena turns a malevolent gaze on the viewer. This expression of Carrington’s inner world stretches most notions of self-portraiture. What, after all, is the self and where does it begin and end?

Swedish artist Helene Schjerfbeck painted herself in a series of nightmares. In her eighties, anxious, lonely, dying of cancer, she produced twenty self-portraits. In most of them she is an apparition, “an other-worldly being in swirls of brown and beige.” In the last paintings she stares ahead, barely alive, barely human.

The story of Gwen John, sister of the more famous Augustus John, is a painful example of a life overwhelmed by force of circumstance. Illness, poverty and misplaced love might suggest a victim, but her superb self-portrait, painted in her mid-twenties, shows her as strong and self-contained, demure yet amused.

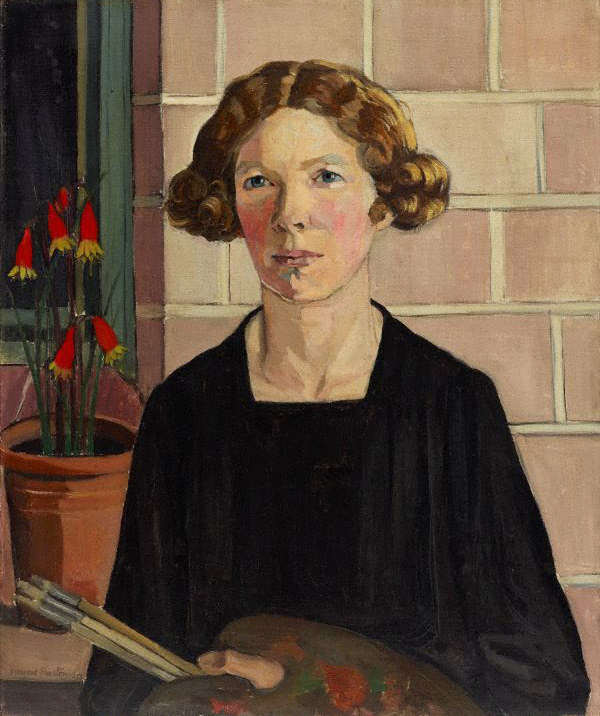

“I am not a flower”: Margaret Preston’s only self-portrait (1930). Art Gallery of New South Wales

Australia’s Margaret Preston had few doubts; hers is a history of triumphs and blunders. As Higgie says, Preston’s fascination with Indigenous art coexisted with a staggering ignorance and insensitivity to cultural trespass. She appears to have painted herself only once, on request. She wasn’t enthusiastic about the task. “I am not a flower,” she said. “I am a flower painter.” By contrast, Nora Heysen did many self-portraits. Whenever she changed her place of living, she would start by painting the person she knew best, herself.

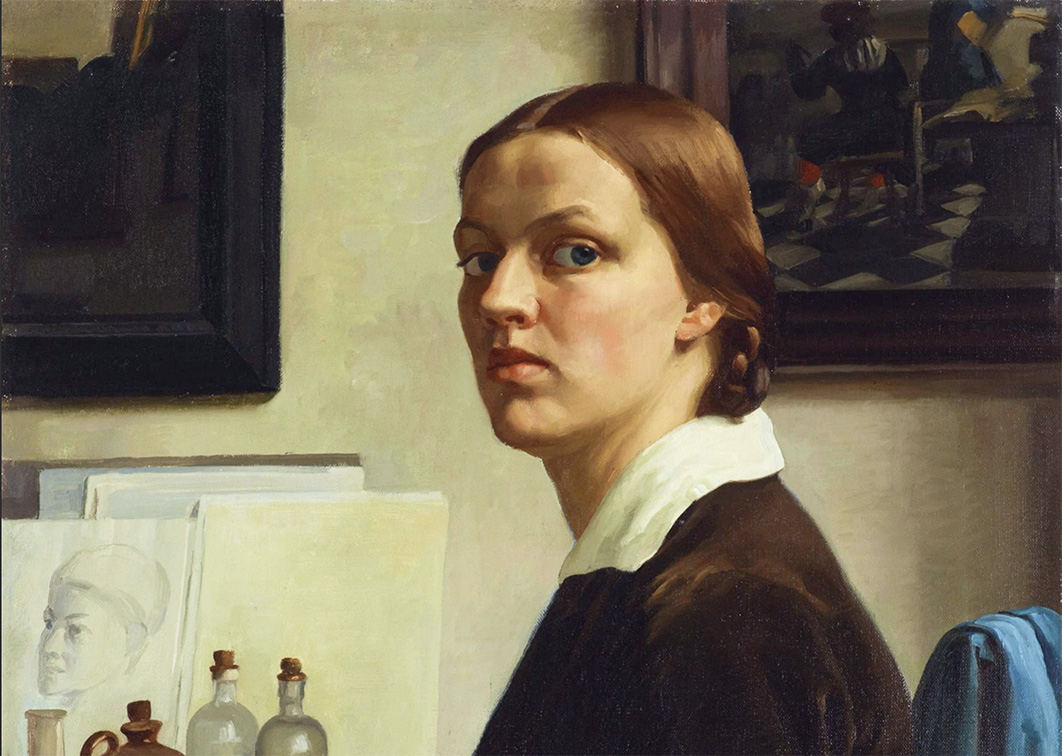

Heysen’s self-portraits show subtle shifts in mood. Often she is seen at her easel, absorbed. In one painting, she turns away from her work, displeased by an interruption. There is no clutter in her studio. Her clothes are in clear, bright colours, plain and smooth as her neatly braided hair. The mood is one of composure, a quiet certainty without assertiveness. As the daughter of the famous Hans Heysen, she needed to be reassured about her independent self: her self-portraits affirmed her separateness. Heysen’s private space may seem limited, but it was her own.

Jennifer Higgie is an Australian art historian and screenwriter who now lives in London. Because her wide-ranging, generous and perceptive book can give no more than a selection from 500 years of women’s self-portraiture, it seems ungrateful to complain of omissions. Yet, in a study that includes self-portraits by artists from many cultures, some space could have been found for Indigenous Australian women. One example: Julie Dowling’s Self-Portrait: In Our Country (2002) carries the burden of her family history.

Higgie skates rapidly over colonial Australia, where she finds nothing of interest. Georgiana McCrae is an obvious omission. Trained in London, with professional experience in 1830s Edinburgh, McCrae was forbidden by her husband from painting for money. Her career ended after her marriage and settlement in Port Phillip. She did, however, paint portraits of family and friends. The most relevant to Higgie’s study would be McCrae’s early self-portrait, coupled with her much later portrait of “Eliza” of the Bunurong tribe. Eliza’s pose, with one hand at her breast, matches that chosen by McCrae for her own image. The young Georgiana looks confident, even coquettish, while Eliza’s gaze is patient, expecting nothing. Painted at a time when McCrae’s hopes had dwindled, Eliza’s portrait may express the artist’s empathy.

In an art world that didn’t accept women as equals, the self-portrait was an assertion of individuality. “This is who I am,” these artists say. It’s their response to those who questioned their right to a career in art with the putdown of “Who does she think she is?” Jennifer Higgie’s spirited and engaging book shows that there are as many answers to that question as there are individuals. Their versions of self, in many moods and modes, encompass worlds of experience and achievement. •

The Mirror and the Palette: Rebellion, Revolution and Resilience: 500 Years of Women’s Self-Portraits

By Jennifer Higgie | Weidenfeld & Nicolson | $39.99 | 336 pages