This time, it wasn’t only the long flight that made me feel Australia and Europe are worlds apart.

As I left Melbourne last Thursday, near the end of Australia’s hottest month on record, the temperature hovered just below 40 degrees. In earlier years, a day like this would have been considered part and parcel of summer, and perhaps an opportunity to hit the beach after work. Not so this summer, when scorchers have been associated primarily with an increased risk of fire. On the day my plane left, large bushfires continued to burn in New South Wales, Victoria and the Australian Capital Territory, while new fires had started in Western Australia and Tasmania.

As we touched down in Hamburg the following winter’s day, I was met by temperatures more typical of spring. Throughout Germany, January 2020 was one of the warmest winter months since the beginning of systematic measurements in 1881. While the change has been as noticeable in Germany as it has in Australia, its consequences for Germany’s weather have not been considered all bad. But the fact that summers have become warmer and lasted longer hasn’t stopped many, if not most, Germans from becoming deeply worried about climate change.

Australians’ concern over climate change has been prompted by droughts, floods and fires at home. Germans, by contrast, are as alarmed by global as much as by local changes in weather patterns and their impact. They tend to point to the melting of ice in the Arctic, the desertification of the Sahel and extreme weather events in the Americas, Asia — and Australia.

So it isn’t surprising that the bushfires have received a lot of coverage in Germany and elsewhere in Europe. While the Australian media have paid particular attention to the loss of homes, the fires’ impact on the built environment has hardly featured in the German media. Here, the focus has been on the loss of wildlife and the destruction of a swathe of Australia’s forests.

Much of the German coverage has also focused on Australia’s ranking as the world’s largest polluter on a per capita basis and the fact that its government has been reluctant to combat climate change. Australia’s role at COP25, the Madrid climate change conference in early December, was widely reported and roundly condemned. Its refusal, alongside Saudi Arabia, the United States and Brazil, to agree to more ambitious targets led news bulletins on 14 and 15 December, the concluding days of the conference, and featured in long articles in the newspapers.

“Australia is considered the secret villain of the climate conference,” the Berlin-based Tagesspiegel reported. “Environmentalists are amazed at Australia’s stubbornness in Madrid. Because the country is well positioned economically, it would be easy for the government to launch renewable energy projects.”

In Europe, bewilderment is a common response to the Morrison government’s climate policies. Most commentators find it difficult to fathom why complacency and denialism prevail on a continent, perhaps the most vulnerable of all to climate change, whose people seem to have the resources to transition quickly to a net carbon-neutral economy and lead the world in developing innovative renewable energy technologies. But how to explain that Australia’s response to climate change is shaped, as much as anything, by its culture wars? Or that the Australian coal industry receives government subsidies while the parties currently or previously in government happily accept donations from the coal industry?

Australians, for their part, seem not so much puzzled by overseas responses to climate change as largely oblivious to them. While the European media devoted much attention to Australia’s position at COP25, their Australian counterparts showed little interest in the conference’s deliberations. Not only that — most of them also ignored the concern voiced in other countries about Australia’s intransigence.

That concern matters. The more people become alarmed about the rate of climate change and appalled by the behaviour of rogue states such as Australia, the more likely it is that they will put pressure on governments and businesses to take a stance.

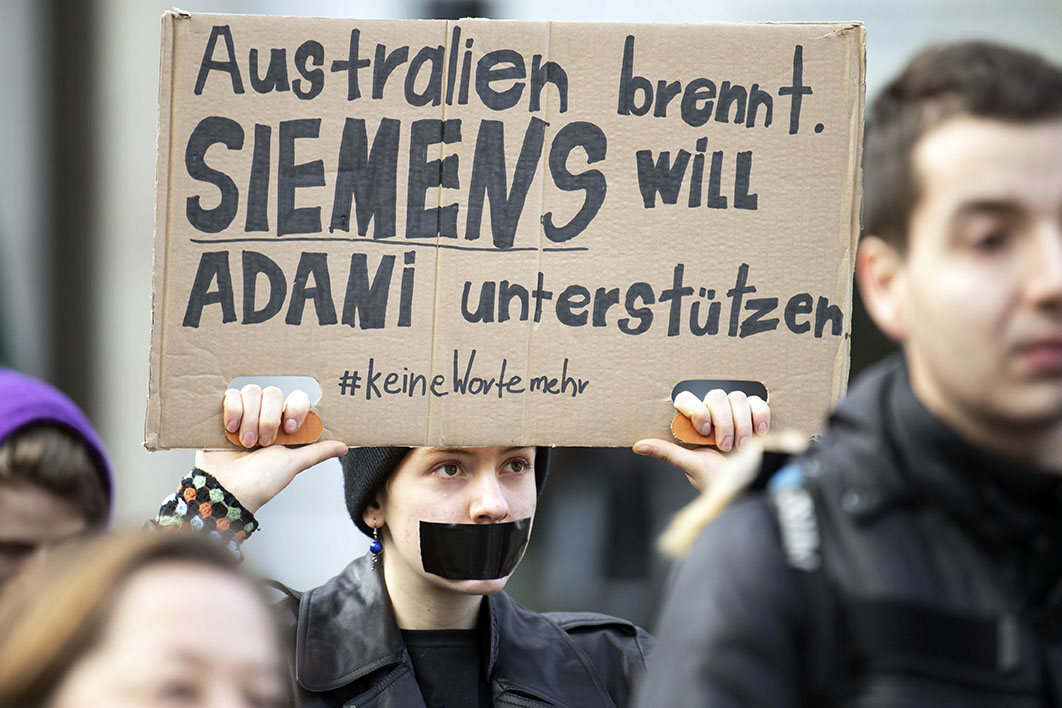

European businesses are already feeling the pressure. The first news item I saw after touching down in Hamburg concerned a demonstration outside the Siemens offices in Hamburg. In one of a series of protests during January, sixty-five members of Fridays for Future picketed the offices early in the morning in protest at Siemens’s decision to provide signalling equipment for the railway line that will service the Adani coalmine in Queensland.

Siemens’s decision not to cancel the contract is only half of the story. On 12 January, Siemens boss Joe Kaeser announced that “there is a legally binding and enforceable fiduciary responsibility to carry out this train signalling contract” (while at the same time reserving “the right to pull out of the contract if our customer violates the very stringent environmental obligations”). But he also bent over backwards to reassure critics about the company’s green credentials. “Siemens, as one of the first companies to have pledged carbon neutrality by 2030, fundamentally shares the goal of making fossil fuels redundant to our economies over time,” he said. Earlier he had intimated that the contract was so small that it had “slipped through” the net, and that new control mechanisms had been put in place to ensure that Siemens avoids making a similar mistake in the future.

Kaeser’s misgivings about the contract were also obvious when he addressed a 3000-strong business council meeting in Berlin on 27 January. Before he could speak, a young climate activist mounted the stage and gave a short speech that was applauded by the audience. Not only did the organisers let her speak; Kaeser afterwards paid his respects to her concerns and said he wished that she had brought fifty or one hundred of her friends along and stayed for the meeting. This isn’t a sign of an ideological commitment to environmentalism, of course: it is good business sense. International corporations like Siemens have long recognised that there is money to be made in the transition to carbon-neutral economies and no future in fossil fuels.

So far, the protests against Siemens’s involvement in the Adani project have been unsuccessful. Long term, though, the pressure on companies involved in coalmining in Australia, and on the banks that fund projects like Adani’s, could pay off. The decisions by the Queensland and federal governments to grant the necessary approvals for the Adani mine may mean little if the company fails to raise the capital required to dig up the coal.

Why should young Germans feel strongly enough about a coalmine in Queensland to picket Siemens’s headquarters in Hamburg? While many Australians seem to believe that Australia’s natural environment belongs to them (and so it is up to them to either trash or preserve it), elsewhere, in societies that haven’t been shaped by settler colonialism, nature is considered to be part of humankind’s heritage. From a German perspective, a project that endangers the Great Barrier Reef is as bad as one that threatens to destroy the famed mudflats of the German North Sea coast.

And while the Morrison government may believe that it is entirely up to Australia to decide whether to mine and export coal (or uranium, for that matter), such beliefs are not shared by many outside Australia.

But the impact of civil-society pressure on companies investing in Australia is only one consequence of a global awareness about the urgent need to tackle climate change. Governments that implement policies leading to higher electricity, petrol and house prices in order to change consumer behaviour are likely to make efforts to ensure that other countries don’t take advantage of the price differential.

The European Union, which is committed to such policies, expects its trading partners to abide by the same environmental standards it is prescribing for its member states. Australia has been confronted with those expectations during the current negotiations about a free trade agreement, which are reported to have hit a snag because of the insistence by Australia’s second-largest trading partner that Australia meets certain climate change targets. The EU’s expectations mean that trade minister Simon Birmingham is kidding himself when he claims that FTAs are “overwhelmingly commercial undertakings between countries” and that they should “focus on commercial realities.”

Even without an FTA, Australia wouldn’t necessarily be able to evade the EU’s expectations. EU president Ursula von der Leyen has suggested that the European Union penalise countries that don’t pull their weight when it comes to combating climate change. As she said in a recent speech at the World Economic Forum in Davos:

[T]here is no point in only reducing greenhouse gas emissions at home, if we increase the import of CO2 from abroad. It is not only a climate issue; it is also an issue of fairness. It is a matter of fairness towards our businesses and our workers. We will protect them from unfair competition. One way for doing so is the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism.

So far, the carbon border adjustment mechanism (or carbon border tax) is little more than a thought bubble. But as the sense of urgency about climate change increases, it could turn into a firm policy before too long.

The idea that countries with policies detrimental to the effort to tackle climate change ought to be penalised is not new. Last year, Norway and Germany suspended aid to Brazil in response to the Brazilian government’s condoning of deforestation in the Amazon Basin.

Once there is broad agreement globally that CO2 emissions need to come down fast, it is also conceivable that the UN Security Council will be given the task of ensuring that countries do their fair share. The pressure on Australia may well come in the form of sanctions and tariffs that will hurt an unprepared economy.

This is not the first time that many Europeans have been aghast at Australian policies. Earlier, Australia’s Indigenous policies — particularly the Howard government’s refusal to issue an apology and successive governments’ refusal to enter negotiations about a treaty — and its asylum seeker policies have scandalised many people outside Australia. Then, too, the main response was one of bewilderment. Why is a country as affluent as Australia behaving in such a mean-spirited manner?

The Australian government may reason that it has nothing to fear from its steadfast commitment to the local coal industry, because international condemnation of government policies harmful to Indigenous people and non-citizens proved inconsequential. But in those two cases, the argument that the treatment of first nations peoples and asylum seekers was a sovereignty issue had some traction. And besides, Europeans may have sympathised with marginalised Aboriginal people and incarcerated “boat people” but they did not identify with them.

That isn’t the case this time. Nobody outside Australia thinks that Australia has the sovereign right to pursue policies that contribute to the destruction of the Great Barrier Reef, to name but one example — let alone to pursue policies that hasten global climate change. Many in Europe take the Australian government’s extremist views on climate change personally — this is no longer about other people whose rights need to be upheld. It is about our future.

The Australian government argues that other countries, including those of the European Union, have also been slow in responding to the challenge of climate change. That is indeed the case. But most governments in the global north now recognise the catastrophic dangers posed by climate change, and are committed to act. And they are often called on to act by electorates that believe current government policies don’t go far enough.

The Morrison government is also hiding behind other recalcitrants, notably the United States. The idea that Australia could somehow be shielded from the anger of countries that try to tackle climate change is a dangerous illusion. There are now only two or three other governments that share Canberra’s extremist views. True, the all-powerful US government is one of them. But emissions trading schemes cover much of the United States already; in fact, California’s is second in size only to that of the European Union. And if anybody but Donald Trump were to win the elections in November, Australia would quickly find itself truly isolated.

It amazes me how unprepared the Australian public seems for the eventuality of other countries turning on Australia because it is seen to be wilfully ruining the commons. Australians ignore the resolve of other countries to tackle climate change — and overseas awareness of Australia’s role as an unrepentant contributor to global warming — at their peril. •