First published by Renew Economy.

So, the battlelines have been set. Labor has adopted the 50–50 path to 2030 (50 per cent renewables, 50 per cent fossil fuels), arguing that a transition to clean energy is necessary and that consumers will actually benefit from cost reductions. The Coalition has responded by entrenching itself in price-scare mode.

The 50 per cent target is terrific news. Should Labor get into power, it will mean a long-term policy setting, a clear signal to the renewable energy industry to invest, and a clear warning to many ageing coal generators that their time is over.

Analysts are crunching the numbers on how the target could be achieved. Ric Brazzale of Green Energy Trading says it would require another 14,000 megawatts of large-scale renewable energy to be built between 2020 and 2030. More than half of this, analysts say, would likely be large-scale solar, possibly including solar towers and storage, and perhaps even wave energy and some geothermal. And it won’t cost much.

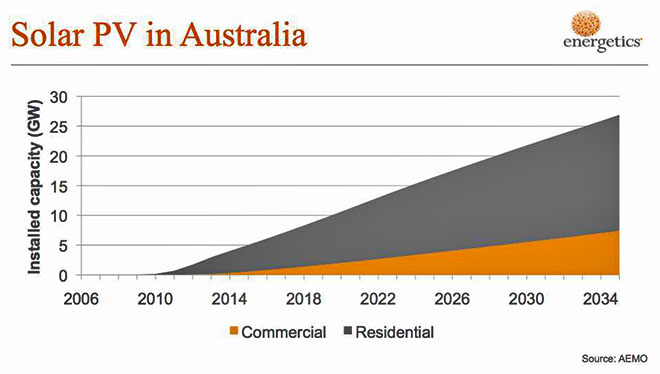

But meeting the target will depend significantly on energy consumers – households and businesses – continuing to install rooftop solar and battery storage at significant rates. Brazzale estimates that the amount of rooftop solar needed to meet that target will be more than 16 gigawatts, four times the amount already installed on the nation’s rooftops. But private forecasts suggest the level of household capacity could end up being much higher.

Bloomberg New Energy Finance believes there will be 37 gigawatts of rooftop solar in Australia by 2040. It suggests that rooftop solar, both on houses and on large warehouse-type buildings, will help push Australia’s renewable share to 37 per cent by 2030, even on current settings – by which time there will already be more than 21 gigawatts of rooftop solar.

Gordon Weiss, of consultancy Energetics, last week presented this forecast for the level of solar PV heading towards 2040. It was based on data and forecasts from the Australian Energy Markets Operator, but it was as optimistic as Bloomberg’s estimates, with more than 20 gigawatts of rooftop solar by 2030.

But these forecasts – or, in Labor’s case, targets – are only going to be achieved if the playing field is not tilted against consumers by incumbent utilities and pricing regulators (and the Murdoch media). Rises in fixed prices and attempts to saddle solar households with added costs are a taste of what may follow.

This presents a fascinating conundrum that will demand a careful response from federal leaders such as Shorten, and their state counterparts. For the past few decades, energy consumers have been forced to take whatever the industry has chosen to give them – and it’s mostly been coal-fired power at a cost that exceeds that of just about any other country.

That is changing rapidly. Consumers – both businesses and households – can produce their own power, and they can store it. What’s more, numerous studies show they can already do that at a lower cost than the grid. A few more cost cuts and they might even be able to do it without the grid. As a report last week from Bloomberg New Energy Finance showed, a 4 kilowatt solar system with 5 kilowatt-hours of storage costs less than grid power. A new battery offering from LG Chem brings the price down even further.

As I reported this week on One Step Off the Grid, the costs of combining a 5 kilowatt rooftop solar system and a 6.4 kilowatt-hour battery storage array, with a 5 kilowatt inverter, are already down to around 18c per kilowatt-hour. And this is at the quality end of the market.

This development poses huge challenges: for consumers trying to get their minds around the technology, for incumbent utilities wondering what the hell it means for their business model, and for policy-makers and regulators wondering what to do about it.

But change is definitely needed. The current energy market is based on old systems of centralised technology and centralised thinking. And the business models that dominate today were based largely on gilding the lily.

Networks were incentivised to build big networks, lock in double-digit returns for that investment and send the bill to the consumers. Those costs now account for nearly half the consumer’s electricity bill in most states and provide most of the incentive for consumers to produce and store their own energy.

The generation companies were just as guilty, encouraging consumers to consume as much as they can, particularly in peak periods, and cashing in on those demand surges when prices soared to $12,000 per megawatt-hour. They obtained a quarter of their annual revenue from just thirty-six hours of such events a year. The retailers were happy to cash in too by sending out bills with a handsome “retail margin.”

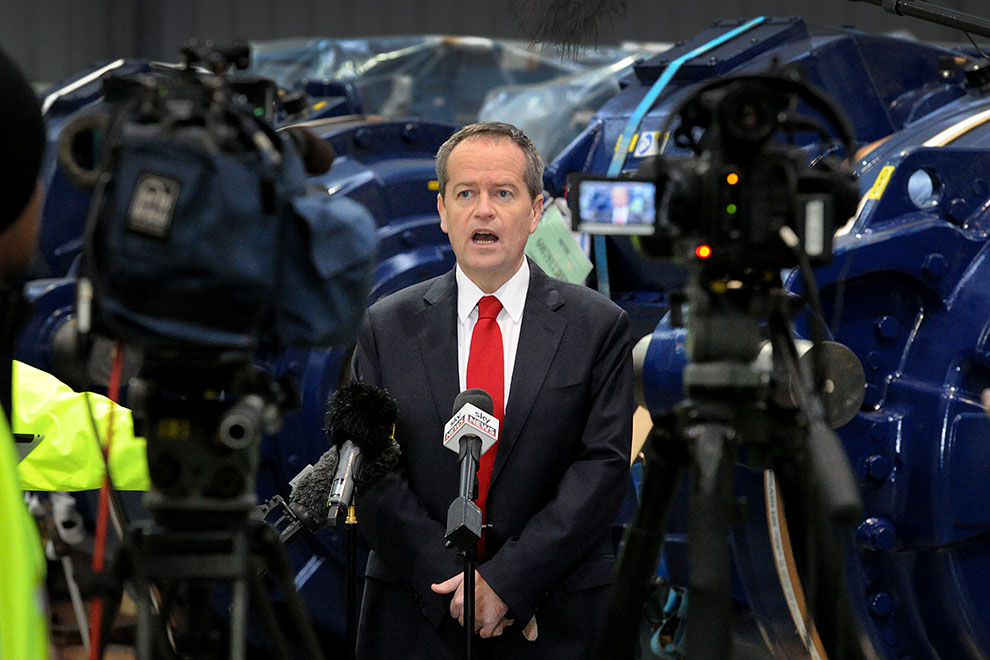

Bill Shorten appears to recognise the change that is happening. He speaks of the opportunities of rooftop solar and battery storage, but it is important to note these will only be deployed at scale if the walls surrounding the incumbents are removed by regulators. The incumbents need incentives to change, not to remain the same.

Europe is in the midst of a fascinating debate about how the energy system should be redesigned. The European Union is considering several proposals, but the bottom line is this: “Market rules need to be updated to the reality of a much more decentralised system where renewables and the consumer are king.”

That requires reform at the retail level and in the wholesale markets. Retail reform is critical to ensure that distributed generation – solar and storage – delivers the cost savings that it promises, without shoring up the sunk investments of network operators and utilities. Increasingly, though, the lines between the retail markets and the wholesale markets will blur. New smart software is allowing consumers not just to trade among themselves and share their output – if the rules allow – but also to engage with the wholesale market.

On the wholesale market, a lot of work needs to be done. Right now, the absence of a carbon price or efficiency standards means that there is little to drive polluting coal-fired power stations out of the market. Australia’s huge coal-use capacity, much of it paid for or subsidised by governments, has been fully depreciated and produces at a low marginal cost. Somehow, those coal-fired generators need to be forced out.

The energy incumbent’s lobby group, the Energy Supply Association of Australia, is warning of higher prices from an elevated renewable energy target, and its argument has been picked up gleefully by the Coalition. The ESAA argues that while a 30 per cent target by 2030 would – according to the Coalition’s own Renewable Energy Target Review – lead to a lowering of wholesale prices, this would only be temporary. A 50 per cent target would force so much extra capacity that there would be no price signal for wholesale generation. The ESAA even lamented the closure of the two coal generators in South Australia, forced out by wind and solar, which now account for 40 per cent of that state’s electricity demand.

But this is what is supposed to happen. Short of artificially extending the life of the existing generators, which no one would contemplate unless they completely ignored climate change, Australia’s coal fleet will gradually be closed down over the next ten to twenty years.

Even without a renewable energy target, this would force wholesale prices to rise. That means that by 2030, or even before, the grid will need new capacity. And when that happens, new-build wind and solar energy will be competing against new-build coal, gas or even nuclear. It is pretty clear which technology is going to win that battle. •