WALTER Balls-Headley, a Cambridge-educated physician and lecturer at the University of Melbourne on midwifery and women’s diseases, thought that something was very wrong with modern civilisation in Australia. In The Evolution of the Diseases of Women, published in 1894, he condemned late marriage, which he attributed to men’s love of pleasure, comfort, socialism and strike action, and women’s taste for tight-lacing and education. There was no reason, he said, “why the satisfaction of the sexual instinct and the act of propagation should be deferred to such a late age of life.” Neither animals nor natives delayed marriage and childbearing so unnaturally; nor did they wear tight-fitting dresses. For Balls-Headley, women existed to bear children; men’s role was to provide for them. Accordingly, educated women posed a racial problem:

[H]igh mental culture is antagonistic to healthy sexual development and childbearing… These women, who are apt to be highly attractive by their refinement of feeling and appearance, are frequently devoid of sexual appetite of any kind…

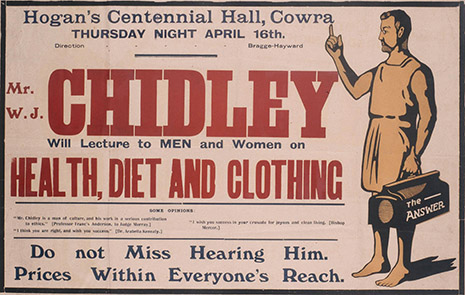

Balls-Headley was a distinguished professional with the status and privileges that such men enjoyed even in the dangerously over-civilised Antipodes. William James Chidley, by way of contrast, was a poor man who ultimately paid for his conviction that the sexual life of the people was unnatural by suffering public condemnation, criminal prosecution and confinement in an insane asylum.

Chidley was born in Melbourne around 1860, the son of a toymaker who was involved in a “free love” sect devoted to the teachings of the Swedish philosopher and seer Emanuel Swedenborg. Living mainly around Melbourne and Adelaide, the younger Chidley supported himself by producing drawings for medical texts of the very kind in which Balls-Headley reflected on the problems of modern humanity.

From his wide reading and an active but guilt-ridden sex life, Chidley developed the theory that there was something profoundly wrong with the way in which modern people had sex. The introduction of an erect penis into a vagina, he said, was unnatural and produced shocks to both men and women that led to their physical and mental deterioration. As he explained in his 1911 pamphlet, The Answer, “the crowbar has no place in physiology.” Sex, claimed Chidley, should only occur in the spring, when the vagina would act as a vacuum and so draw the flaccid penis inside. Like Balls-Headley, Chidley based his views on observations of the animal kingdom; he was particularly impressed by the lessons offered by the sex life of horses.

Although Chidley gained a following and found people willing to defend him from state persecution, he was also widely regarded as a crank. Yet he and Balls-Headley occupied some common intellectual territory; notably, a conviction that over-civilisation was producing racial degeneration. Where, however, the medical man saw a falling birthrate and women’s improved social status as its clearest manifestation, Chidley blamed a social order based on an aggressive male sexuality. Balls-Headley’s theories were largely consistent with a belief in a woman’s role as a breeding machine, and were bolstered by his professional standing. Chidley’s ideas challenged the patriarchal social order that Balls-Headley defended and were the work of a self-educated radical and freethinker.

BALLS-HEADLEY and Chidley were each intervening in a public debate that revealed a society preoccupied with sex and reproduction and increasingly convinced that the future of humanity depended on how it organised them. It is not that a Victorian reticence was cast aside in favour of openness. Rather, participants in public debate now developed new ways of talking about sex. In doing so they drew on the emerging field of sexology, but it is far too simple to argue that science was displacing religion or morality. Modern understandings of sexuality in fact often developed out of an intense spirituality that refused to reduce erotic drives to biology. Sexual behaviour was now less likely to be seen as a response to environmental conditions, or some momentary stimulus or impulse. Sex was becoming central to the meaning of self-hood; it was at the core of character.

Two phenomena stand out as having done most to shape the sexual history of the period. One was the dramatic decline in the birthrate in the period after about 1870, which worried Balls-Headley. This trend caused a panic about the prospect of “race suicide,” but also contributed to a crisis in the middle class. Respectable women’s adherence to a certain code of sexual behaviour became a critical marker of identity, thereby distinguishing them from the “depraved” lower orders. But the widespread practice of birth control among apparently otherwise good and decent women from the better-off classes underlined for some middle-class men a sense of conventional morality’s fragility. It suggested that new and insidious forms of sexual depravity were infesting the very people – “respectable” women – who really ought to be the strictest guardians of propriety.

The judgements of such men about the drop in moral standards were confirmed by the connection they saw between the image of the “New Woman” associated with the feminist movement, and the decline in the birthrate. Feminists discussed the “sex question”; they advocated smaller families; they preached the evils of modern marriage; they argued in favour of improved educational opportunities for women; a few were even known to advocate contraception – it did not take much for a hostile judge to put all of this evidence together and hang the defendant. Feminists who blamed declining birthrates on the prevalence of VD among men seemed unconvincing in the face of such an overwhelming case for the prosecution.

The growing preference for small families would have been bad enough for the pronatalists but because it was accompanied by indications that some women were achieving this end through contraception rather than abstinence, the phenomenon raised profound questions about female sexuality. If sex was not essentially for reproduction, marriage seemed to become “a mere sexual compact” and sex just a “pleasant amusement.” Moralists worried that women were having sex for pleasure, rather than out of a sense of duty to society or their overwhelming desire for motherhood. Moreover, if women could have sex without the natural consequence – pregnancy – their chastity would be sorely tested. T.P. Lucas, a doctor, addressed the Young Men’s Christian Association to this effect in Melbourne in 1885. “Nature is one,” he declared,

and laws apply generally to the whole animal kingdom. In accordance with this law woman at stated periods would be prepared for generation. And so she is. If, however, the fact were made known to her intelligence as it is to the lower animals, no woman could be virtuous; and humanity would sink into animalism, and collapse socially; and so the law is added to, and woman is specially defended when she is weakest.

This explanation portrayed female sexual morality as a very fragile thing indeed, suggesting that women had a sexual appetite that could not be reduced to the status of cover for maternal instinct. If the fear of pregnancy and its corollary, female “modesty and a fear of shame,” constituted a “special safeguard” designed by God to defend womanly virtue, contraception posed particular dangers to the moral order. Henry Varley, a fiery Protestant clergyman and social purity campaigner, believed that the “disgusting doctrines” (regarding birth control) found in popular texts led to sexual excess, a danger to the morality and health of married couples. The panic over Australia’s declining birthrate was about the contested meaning of female sexuality. And it was about the fundamental purpose of sex.

The other major development of the period was the campaign to reform male sexuality. The historian Marilyn Lake has claimed that, in the 1890s, there was a struggle for control of the national culture between men and women – a sex war – and that male sexual behaviour was an issue at the heart of this conflict. Writers in the famous Sydney Bulletin, she suggests, celebrated the wandering bushman in his freedom from domestic constraints, and so produced a political position she calls “masculinism.” It upheld the right of men to enjoy various pleasures and freedoms without the interference of female busybodies, nosy parsons or a nanny state. Feminists, on the other hand, condemned the Bulletin’s idealisation of the nomadic bushman, and favoured a domesticated masculinity in which men assumed the responsibilities of a breadwinner while treating their wives with gentleness and respect.

But what was the outcome of this sex war? Did it have a clear winner? Lake believes so, suggesting that it was not the vision of male freedom from domesticity but rather the feminist movement’s ideal of a more self-controlled and chivalrous masculinity that emerged triumphant. The victory of the domestic ideal, Lake argues, was manifested in Justice H.B. Higgins’s Harvester judgement of 1907 and the concept of the family wage that it enshrined. In his famous Arbitration Court ruling, Higgins assumed a male breadwinner who would provide for his family through wage labour; not one who would waste his family’s income on prostitution, extra-marital sexual conquests or drinking and gambling. The family wage concept also registered the declining size of Australian families. Higgins allowed for three children; a basic wage founded on this assumption before the 1890s could hardly have been taken seriously.

JUST as conventional morality demanded sexual ignorance of women and children, so the state established public rituals whereby it communicated an authorised version of public decency. These were publicly justified as an effort to protect the working classes – especially women and children – from the threat of depravity or corruption. Yet considered as public policy they sit oddly beside the vast number of column inches in the popular press devoted to salacious divorce cases, French goods and abortion remedies, which authorities left mainly untouched. For instance, on 3 June 1906 in Melbourne, T.G. Taylor and P.L. Harkin were arrested and charged with having distributed some sex advice literature written by Taylor’s wife, Dr Rosamond Benham. Benham advocated Karezza, or practical continence: a form of sex in which through the power of thought a couple could supposedly avoid “the final orgasm” in favour of an “exchange of magnetism.” Taylor was sentenced to three months’ imprisonment, while Harkin received one. Their convictions were later overturned by the Supreme Court, but the episode showed that the authorities were prepared to make an example of sex radicals who sought to bring unorthodox ideas before a working-class audience.

William Chidley’s persecution is better known. Chidley’s enemies detected in his ideas the ravings of a dangerous lunatic. But they also worried that the ignorant and impressionable might take them seriously. In Melbourne in 1911, booksellers distributing his recently published pamphlet, The Answer, as well as Chidley himself, were prosecuted on the grounds that there were sections of the book “which would tend to deprave and corrupt the morals of any person reading it.” The court ordered the destruction of copies seized by police. In the following year the bearded and earnest-looking man, now dressed in a simple Grecian-style tunic and sandals, took his message to Sydney for the most famous phase of his career. Although regularly arrested and prosecuted – sometimes simply for wearing his unconventional tunic – the willingness of friends and supporters to pay his fines meant that police were unable to prevent the determined sex reformer from continuing his agitation. After a number of public lectures, police threatened to prosecute any owner of a hall who leased him their premises.

Yet Chidley still wandered the streets, carrying a bundle of his pamphlets, which he offered to passers-by for a small fee. And he continued his lectures, now usually delivered in the Domain or the Botanic Gardens. In August 1912, having been further provoked by Chidley’s plan for a lecture to “Ladies Only,” the authorities assembled a conga line of obliging doctors and arranged for him to be certified as insane and compulsorily detained in the Callan Park Hospital for the Insane. Popular agitation against this blatant abuse of the law soon led to his release but leading doctors continued to campaign for Chidley’s incarceration, arguing that he was suffering from “paranoia.” Late in 1912, the courts also imposed fines on several booksellers who stocked The Answer, although full suppression only came with a Supreme Court decision in 1914.

As authorities in Melbourne and Sydney acted against Chidley, a popular campaign in his defence gathered momentum. Socialists and radicals especially insisted on his right to free speech, although not all Chidley’s supporters were of the left. Archibald Strong, whose politics leaned towards the conservative end of Melbourne’s cultural liberalism, believed that treating either Chidley or his book as “obscene” was “a perfect absurdity.” Strong appeared in court to testify in Chidley’s favour in 1911. But support for Chidley’s right to be heard did not, in most cases, amount to endorsement of his theories. While his condemnation of a thrusting male sexuality was appealing to some feminists, much pro-Chidley agitation was about defending the public discussion of sex, as well as opposing the use of the lunacy laws to silence a sincere enquirer after truth.

By the time of the first world war, William Chidley’s campaign for sex reform was reaching its final, tragic stage. Patrick White, then a very young child in Sydney, recalled Chidley “dressed in his white tunic” and looking “jaunty enough as he passed along the street followed by a laughing, jeering mob.” But arbiters of public morality had long ago judged his opinions unfit for public consideration. Society, they believed, should not hear his crackpot theory that the answer to its ills was sex in the spring between a woman and a man whose flaccid penis would be drawn inside her during their divine union.

Yet the NSW Labor government did not know what to do with its Chidley problem, for he was now a figure attracting considerable public sympathy. While its inclination was to keep him in an insane asylum, his supporters remained vocal in condemnation of coercion. In August 1916 Chidley had been released on certain conditions, these being that he “not address persons, and particularly women, by circular asking them to grant him interviews, in order that he might explain his theory to them.” He was also banned from holding meetings in public parks, nor could he sell his little book on the streets. But Chidley was soon addressing crowds in the Domain and, according to the Chief Secretary, George Black:

there was no feature of sexual intercourse on which he did not expatiate in order to prove that his theory was the only one that should be followed by the human race. He stated that if that theory had been adopted there would have been no war, the conclusion which I drew from that remark being that there would have been no Germans.

So Chidley found himself back in an asylum. In October 1916, as the country tore itself apart over conscription, some of his supporters came up with an apparently ingenious solution. Would the government pay for a passage to either the United States or Canada? The chief secretary’s department ran the idea by the premier, William Holman, but when the US consul was consulted, he replied that his government would regard any such initiative as “an unneighbourly act.” The government let an otherwise attractive proposal drop but not before giving serious consideration to the Canadian alternative. Even the governor was brought in to consider this most important matter of state. But they need not have worried, for Chidley was nearing the end. In September 1916 he had doused himself with kerosene and set himself alight while at Darlinghurst Gaol. The fire was extinguished, but so too now was his fighting spirit. He died on 21 December 1916 of heart disease. The government medical officer added that he believed “the diseased blood vessels were due to syphilis,” a claim subsequently denied by Chidley supporters, including some dissident members of the medical profession.

For all his excesses, Chidley must be considered seriously in any account of the coming of sexual modernity to Australia. Havelock Ellis – to whom Chidley had written in 1899 asking him to “write to me and be my friend” – believed him to be “one of the most original and remarkable figures that has ever appeared in Australia.” Edward Carpenter, the British sex reformer and socialist, was also willing to engage with Chidley’s theories, although he thought his Australian correspondent tended to “ride the sex question to death.” Chidley’s belief that his scheme would some day save the world “from all its misery, disease, crime, and ugliness” implied a sexual determinism that even sexologists such as Carpenter and Ellis could not accept.

But Chidley is important for reasons other than his ability to attract the notice and even respect of famous men. There was his stress on sexual equality between men and women, on women’s capacity for initiative and desire, and on their right to joy in intercourse. As Chidley told Ellis in 1899, “The womb and vagina of a beautiful and healthy woman, believe me, is a living, vital, moving organ, sensitive to a look, a word, a thought, or a hand on the waist: but as we have coition now, a woman and her womb might as well be dead.”

In the current unnatural mode of coition, he added, “some people – especially women… always suffer: their married lives are one long suffering.” In his attention to women’s rights to sexual pleasure, Chidley was a true feminist and radical whose views look forward to Marie Stopes, Germaine Greer and women’s liberation. His notion of the cyclicity of female sexual desire and emphasis on the necessity of a divinely ordained affinity between men and women in sexual relations resemble the famous British sexologist Marie Stopes’s position in her 1918 sex manual Married Love. And like Stopes, he was not writing for an audience of “experts,” even if he desperately sought – and, when he achieved it, flaunted – their approval. Instead, he placed his ideas before common people. Much hostility to Chidley among doctors and the judiciary arose from his status as a layman addressing a popular audience on matters that the medical profession regarded as its prerogative, and which they saw as dangerous if unleashed on the “mob.”

Chidley placed sex at the centre of life. It was for him the principal source of individual misery and social degeneration but also the way to human happiness. A few hardy followers would carry the substance of his teachings into the 1920s, but his main significance lies in the status he gave to sexual joy as the key to the gates of heaven on earth. In this respect, Chidley and The Answer still speak to our own times. •