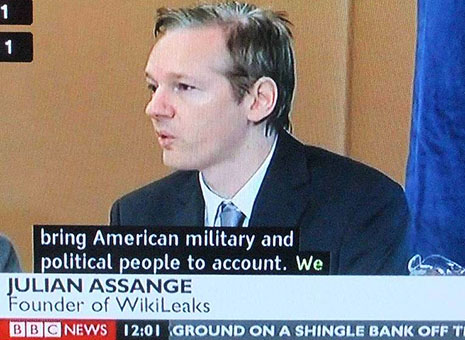

IN RECENT DAYS I’ve been looking for answers to a series of questions raised by the massive WikiLeaks releases over the past two weeks. What is driving Julian Assange? Why is WikiLeaks publicly dumping 250,000 US State Department cables? What does he hope to achieve, and what are his chances of success?

Julian Assange guards his privacy intensely, but we can glean that he is thirty-nine, Australian, a bright kid from an unsettled and by no means wealthy family, whose childhood involved a lot of moving around in country Queensland and Victoria. At the University of Melbourne he was clearly an outstanding scholar in his field, physics. His website archive shows a highly intelligent, intensely idealistic mind at work – a polymath, skilled in computer science but with a keen interest in politics and society.

Importantly, he was still in high school when the Cold War ended in the late 1980s. His politically formative years were thus spent in the Clinton and Bush post–Cold War years of unchallenged American power. The evidence suggests that he doesn’t think in a Cold War framework of good guys (us) versus bad guys (them). For him, it seems that unchecked American power outside a rules-based international order (as seen in the Bush/Blair/Howard years) is the main problem we face. The abuse of American power under George W. Bush’s presidency, especially at Guantanamo and in the Iraq invasion of 2003 and what followed, indelibly stamped his anti-state political outlook.

Assange thinks of the state as an amoral bureaucracy, or “conspiracy” as he calls it, which does evil things unthinkingly because it has the power to do so, and routinely seeks to manipulate and control public information flows and informed public debate on these matters. He is here squarely in the tradition of Hannah Arendt (“The banality of evil”), Zygmunt Bauman (Modernity and the Holocaust) and, of course, Noam Chomsky.

Assange believes that although modern bureaucratic systems diffuse and blur individual responsibility, they do not obviate the need for the exercise of individual conscience. He thinks that if citizens don’t challenge bad outcomes then they are individually responsible for what our state does in their name. In a revealing footnote to an early version of his December 2006 motivational essay, “Conspiracy As Governance,” he answered his own question of where bad governance comes from:

Every time we witness an act that we feel to be unjust and do not act we become a party to injustice. Those who are repeatedly passive in the face of injustice soon find their character corroded into servility. Most witnessed acts of injustice are associated with bad governance, since when governance is good, unanswered injustice is rare. By the progressive diminution of a people’s character, the impact of reported, but unanswered injustice is far greater than it may initially seem. Modern communications states through their scale, homogeneity and excesses provide their populace with an unprecedented deluge of witnessed, but seemingly unanswerable injustices.

Not a few Australians would identify with these thoughts. In the Howard years, human rights activism was energised by many cases of cruelty and injustice; but many activists became progressively more burnt-out trying to fight the seemingly all-powerful state across a range of individual issues. By 2006, Assange would have seen that human rights activism in Australia was all but exhausted.

He chose a different way: not to expend energy on individual issues of injustice, because for him these are merely products of the system of information-controlling amoral states that he seeks to challenge. As the opening paragraphs of his essay put it:

To radically shift regime behaviour we must think clearly and boldly for if we have learned anything, it is that regimes do not want to be changed. We must think beyond those who have gone before us and discover technological changes that embolden us with ways to act in which our forebears could not. We must understand the key generative structure of bad governance. We must develop a way of thinking about this structure that is strong enough to carry us through the mire of competing political moralities and into a position of clarity. Most importantly, we must use these insights to inspire within us and others.

Weblogger Zunguzungu offers an analysis of the intellectual provenance of WikiLeaks. According to his summary, Assange sees a state like the United States as essentially an authoritarian conspiracy. He reasons that the practical strategy for combating this conspiracy is to degrade its ability to conspire, to hinder its ability to “think” as a conspiratorial mind. The metaphor of a computing network is crucial: Assange seeks to oppose the power of the state by treating it like a computer and tossing sand in its working parts.

Assange published a follow-up piece in his blog archive, “The Non Linear Effects of Leaks on Unjust Systems of Governance,” posted on 31 December 2006, a few weeks after his main essay. He noted how different systems of state power are differently affected by leaks:

The more secretive or unjust an organization is, the more leaks induce fear and paranoia in its leadership and planning coterie. This must result in minimization of efficient internal communications mechanisms (an increase in cognitive “secrecy tax”) and consequent system-wide cognitive decline resulting in decreased ability to hold onto power as the environment demands adaption.Hence, in a world where leaking is easy, secretive or unjust systems are nonlinearly hit relative to open, just systems. Since unjust systems, by their nature, induce opponents, and in many places barely have the upper hand, mass leaking leaves them exquisitely vulnerable to those who seek to replace them with more open forms of governance.

Only revealed injustice can be answered; for man to do anything intelligent he has to know what's actually going on.

Assange highlights ways in which secretive, unjust states are subject to two conflicting operational imperatives. Operational information must flow sufficiently widely among a range of operatives for the system to function at all, but information flow that might harm or discredit the regime must be restricted. Zunguzungu again summarises Assange:

[W]hile an organisation structured by direct and open lines of communication will be much more vulnerable to outside penetration, the more opaque it becomes to itself (as a defence against the outside gaze), the less able it will be to “think” as a system, to communicate with itself. The more conspiratorial it becomes, in a certain sense, the less effective it will be as a conspiracy. The more closed the network is to outside intrusion, the less able it is to engage with that which is outside itself…

For Assange, the leak is only the catalyst for the desired counter-reaction. WikiLeaks wants to provoke the “conspiracy” into turning off its own brain in response to the threat. As it tries to plug its own holes and find the leakers, its component elements will destabilise and turn against each other. Assange hopes that in self-defence the national security state will make itself dumber and slower and smaller. He concludes that “an authoritarian conspiracy that cannot think is powerless to preserve itself against the opponents it produces.” Kevin Rudd has already fallen into this trap: he blames a loose, weak American national information security system and calls for its tightening-up.

The WikiLeaks cables dump also undermines the claimed superiority of national security information systems over open public information resources. Here, the media are reinforcing Assange’s message. This week the Australian, for example, boasted at length about how everything in leaked cables from the US embassy in Canberra published to date was previously said by reporters or commentators in the newspaper’s own pages.

MANY commentators are stressing the triviality and inconsequentiality of much of the leaked material. This is unlikely to worry Assange, for he must hope that the shortcomings of the material will weaken the credibility of any future arguments for American war-making based on supposedly superior national intelligence. Australians will see from WikiLeaks how naked the emperor really was in the fateful US decision to make war on Iraq in 2003, at the cost of hundreds of thousands of innocent Iraqi lives. It’s to be hoped that Australian governments won’t be fooled so easily again.

We’re seeing how information is spun and processed by powerful governments, how different messages are presented to different target groups of people in allied nations, and how weak allied governments can be bullied or persuaded to cooperate in the violation of their own national sovereignties. (The case of the Swedish military aircraft choice is remarkable here – one wonders what similar unwelcome surprises might lie in store, in future releases of US cables on Australian defence purchases.) It is also clear how Australia under both Howard and Rudd tried to ingratiate itself with the United States by being even more aggressive (verbally at least) than the sheriff himself.

This week’s documents show how the United States cultivates future sources of information and influence over many years in friendly, easily flattered countries like Australia, and how those sources obligingly allow themselves to be milked of insider information at times of political instability: witness the very frank and early reports from Mark Arbib of looming unrest against Rudd in the federal government. Yes, no doubt the content was all in the Australian at the time, but there is still a shock in seeing how an embassy can vacuum up information from long-cultivated friends. Context here is everything: political information officially reported by an embassy from within a friendly country, and the ways that information is collected and reported, have an impact that is distinct from the familiarity of the content.

I don’t think that Assange is trying to discredit and destroy Australian political careers or to break up ANZUS; he knows the power of political networks and alliances to close ranks instinctively in self-defence (as is happening). He is trying, I think, to achieve something – in the long run and on a broader international front – that perhaps is more achievable: to desanctify and disrupt the smooth workings of the association of western national security states around the US centre. Assange clearly hopes that the WikiLeaks diplomatic cables dump – trivial and familiar as some of its content is – will show people that governments have no monopoly on wisdom or information.

His argument was strengthened this week by the inept initial reactions of Prime Minister Gillard and her attorney-general. Julia Gillard said that what Assange is doing must be illegal under any commonsense test and – not seeing her professional error here – revealed that she was asking for a report on what laws he might be breaking. She thus exposed herself to criticism of prejudging a man’s guilt. Robert McClelland awakened echoes of Howard-years illegal renditions by promising to help bring Assange to American justice and to investigate cancelling his passport. It was left to Rudd to restore a sense of proportion regarding Australia’s consular responsibility to protect the rights of an Australian citizen. Gillard and McClelland both later refined their responses, but by that time the outraged Australian human rights movement had become re-energised in support of Assange. Geoffrey Robertson, Julian Burnside and Stephen Keim are on the case now and will be powerful defenders of Assange’s rights.

The hostility to Assange within the American hard right is manifest and dangerous. There will be further attempts to demonise him before he faces the crucial British court decision on extradition to Sweden, from where he would probably soon be extradited to US territory to face charges there, Sweden currently being a compliant US ally. If the real purpose of the sexual assault charges is to get Assange away from British human rights protections then he is in real danger now.

IS THERE a counter-argument? Before George W. Bush tore up the rule book on how the United States should behave internationally, I would have argued there was. It is certainly painfully embarrassing for diplomats and foreign ministers to see well-kept tradecraft secrets unmercifully brought to light – there are no blacked-out paragraphs here as in cables officially released after a safe interval – and to see the mediocrity and irrelevance of some diplomatic reporting. On the other hand, I don’t see that anyone’s personal security has been put at risk by releases so far. Nor do I think that the cables listing vulnerable national infrastructure assets offer any advice that terrorists couldn’t glean from phone books and trade directories.

I see Assange as a product of a particular time of great stress in the international system, the years 2000–08. I remember the collective international sense of relief when Bush’s helicopter flew him out of Washington for the last time. For years, civil libertarians had felt helpless against a coalition of two powerful states supported by a third that had gone right off the rails in terms of proper international conduct. WikiLeaks may be a late overreaction to those abnormal times when three governments broke their contractual obligations to treat their own citizens and the world community with respect and integrity. This moment will pass. But it is tough on Barack Obama that he has to deal with this now as president, when he was not responsible for the radicalisation of Julian Assange.

Let’s conclude with a few reminders about context. Assange has not hacked into US national security information networks: he was offered information by a dissident American whistleblower from inside the system and he accepted it for publication on his website and as an intermediary to major newspapers. If that makes him guilty of anything, then so are his collaborators, major US and European (and now Australian) newspapers, which are publishing their selections of his material and at a rate of their choosing. In the long run, I believe we will all be better off for what he is doing here, even though I would not care to be in his shoes today. •