Tolstoy was wrong, it appears; a happy family can be utterly distinctive, and Lorin Clarke (hereafter Lorin) writes superbly about hers. People will search out her new book Would That Be Funny? for the light it shines on the comic genius of her father, the guarded, generous, reticent, surgical John Clarke (hereafter John) of happy memory.

Many of us still carry grief from John’s sudden death, seven years ago now, chasing birds in the Grampians. Lorin has more cause for grief than the rest of us, but it just doesn’t seem the right word for so joyous a book. Instead, she has taken the time to create something luminous out of her loss. I read this book while coming down with a cold, and it made me feel a lot better, in heart and mind at least; unfortunately, it didn’t seem to do my chest any good.

The family happiness is real and the product of both experience and fortunate choices. It makes you realise that Tolstoy’s tragic vision is not something John could ever have warmed to. Come to think of it, impish and ironic minimalism is not among the more obvious characteristics of War and Peace. In Tinkering (2017) John does Anna Karenina in forty-three words, and the great Russian realist gets knocked off in the third round in The Tournament (2002), despite a high seeding. It’s a path not taken by the satirist with the twinkle in his eye.

Now Lorin, the elder of John’s two daughters, has her say, and shows that she has arrived as a writer. Her metier is the fragment, its supply responsive to local movements of thought and emotion. The remarkable thing is how deftly she deals with sentiment without becoming sentimental, how amusing she can be without becoming (unduly) competitive. The story she has to tell is one of an ensemble, not the more common tale of a towering genius who draws those around him into his vortex.

The central event in the family’s story really is the love of a good woman, Helen McDonald, who married John in 1973, reportedly so that she could work in New Zealand. No romantic nonsense in this relationship — just endlessly inventive and competitive play sustained by laconic affection. This was necessary to heal the wounds, and especially the sense of inferiority, that John bore from his parents’ rocky relationship. For that, the second world war is to blame.

Neva, John’s mother, went to war in Italy as a young secretary and ended up working directly with the major-general commanding the New Zealand Expeditionary Force. Cruelly, she was twice defiancéed (if that’s a word), the second time after hostilities were supposed to have ceased. She returned to New Zealand, married Ted faute de mieux. Like many talented women of her generation, she discovered that she was supposed to rejoice in the life of a housewife, and forget that she had ever had other aspirations or capacities. She loved her children, but came to hate the suburban life.

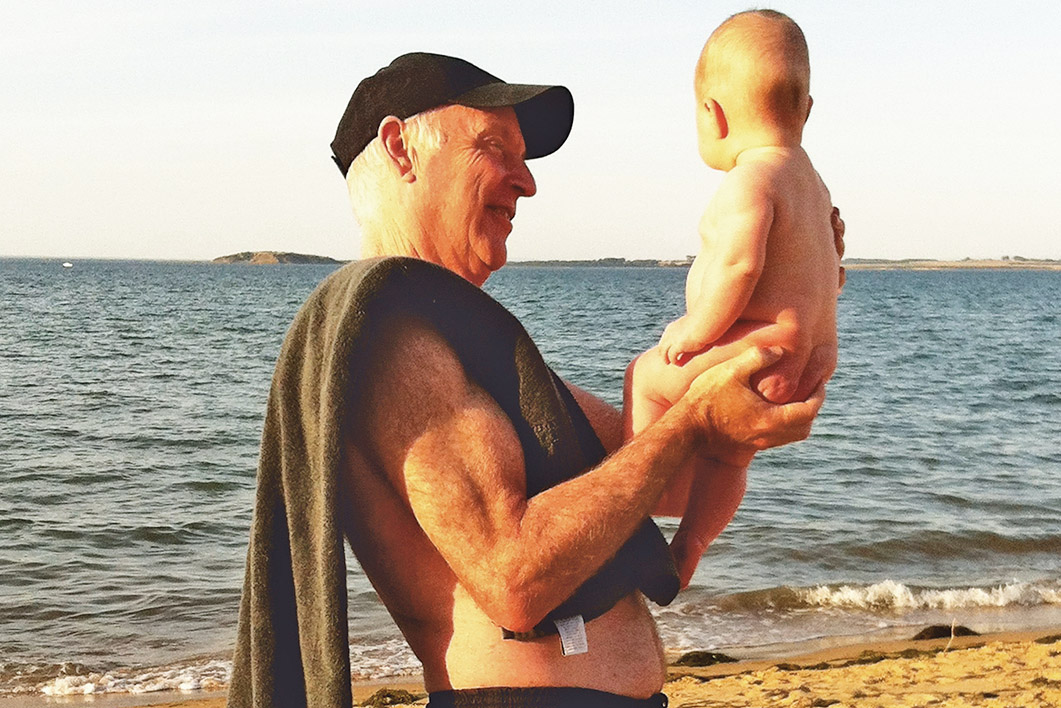

Ted, meanwhile, was a successful and bottled-up retailer, disinclined to talk much about the years he had spent fighting Rommel, or to show much feeling about anything. He was also hard on his eldest son, John, who spent a couple of decades convinced he was never going to measure up. Ted and Neva’s marriage did not last, but long after the divorce, as Nevana and “the White Furry Fellow,” they got over the wounds and discovered separate talents as loyal and quizzical grandparents.

The crucial plot point came when John met Helen and her warm and supportive family, especially parents Charlie Boy and Gina de Babe (nomenclature is mostly for playing with in Clarke-world; the book comes with a useful glossary). Without this happy turn of fate there would have been no Fred Dagg and John may well have been just a funny bloke who remained a bit tortured and never amounted to much. With Helen and her family, his comic talent had found an anchor in a hyper-verbal but emotionally warm world. Some humourists seem to need the spur of insecurity to create, and a few wreak havoc in their private lives for fear of losing the creative spark. Not John and Helen.

Their warm homes in Greensborough and Fitzroy welcomed friends and extended family, then two daughters, Lorin and Lucia (“the sisterhood” as far as they are concerned, and the inspiration for John’s “Federated Under Tens”). The only battles seem to have been over the best way of framing words: “A topic our father could speak about for hours was how helpful form could be when writing something. By form he meant format, schema, structure, configuration, style, even genre. Sports scores. A news report. A legal letter. Furniture assembly instructions.”

Expression was always about craft in John’s work, and parody was a primary move in pretty much everything. The energy came from a sure inner compass straining against the automatic words of fools or the devious rhetoric of knaves. From Fred Dagg’s broad accents to the arcane terminology of farnarkeling and the two minutes and forty-six seconds of the Clarke and Dawe episodes, form was fundamental — not quite more important than delivering a message about fools and knaves, but utterly co-dependent. He’d have hated the job description of content-creator, because content is just stuff until you find the shape that belongs to it.

The business of writing for John and Lorin is not to cover things up, but to pierce their real significance. If you seek to understand the corruption of corporatised sport, can you do any better than this?

MR WILSON: So you’ve measured the track?

JOHN: Yes, we’ve measured the track, Mr Wilson.

MR WILSON: So you know how long the 100-metre track is?

JOHN: Yes, we do.

MR WILSON: Okay.

JOHN: How long is it, Mr Wilson?

MR WILSON: You know how long it is.

JOHN: I want to hear you say it.

MR WILSON: Ninety-four metres. (The Games)

This is the pure and precise anger of John’s satire, focused laser-like on the sin and its systemic sources in human weakness, while being almost gentle on the sinner. Could anyone really resent being caught up in his apt contempt? It has the detachment of justice and none of the animus that drove, say, Barry Humphries’s genius for comic disgust. John as satirist is the tolerant uncle who lets you know that you’ve fallen short. Maybe you will do better next time.

And we miss him. Imagine what he would have made of Morrison of the many ministries!

Meanwhile, in Would That Be Funny?, Lorin has found the right form to tell the family story. She mixes fragments of intimacy, blocks of narrative in far from rigorous chronological order, found documents, and many lists. The book is nearly always funny, apart from when it is suddenly intense, nearly always kind and celebratory, except when it is emotionally ruthless. It dances on the tightrope of tone that memoir demands, and succeeds with vim and lucidity. She grants us entry to a family of super-intelligent and playful eccentrics strangely like the aunts and uncles in the most perfect item in the Complete Book of Australian Verse, “A Child’s Christmas in Warrnambool.”

Might Would That Be Funny? work for readers who do not know and love the works of the father? I can’t say, because my powers of detachment cannot take me that far outside the memory of John. But I think the book might just be good enough to lead new audiences to his works. It is certainly a treat if you miss that weekly moment of sanity on the 7.30 Report.

The Clarkes’ humour is polished to a fine edge, but it welcomes anyone who wants to laugh with those who dream of a juster and kinder world. One paragraph nails that:

The sisterhood regarded Dad as the Great Relaxer. Always zooming out on the picture and reminding us we’d be okay. He’d make me snort with laughter on my way to an exam I was terrified I’d fail. He’d say, “We still love you if you fail, you know. I don’t want to boast but I’m the clubhouse leader when it comes to failing stuff.”

When Beckett writes “Fail better” it comes through as a grim admonition. The Clarkes can make the same advice sparkle.

John’s genius was, often, for stopping. He did it in life as well. Many of us miss him, but none as deeply as the happy family he left behind. That is clear on every page of this fine and amusing memoir.

As an admirer of your father’s work, as a father of daughters, as a believer in the resilience good humour can give us, I just want to say, “Well played, Lorin.” •

Would That Be Funny? Growing Up With John Clarke

By Lorin Clarke | Text Publishing | $35 | 288 pages