Sex in the Brain: How Your Brain Controls Your Sex Life

By Amee Baird | NewSouth | $29.99 | 224 pages

The cranium-fondling phrenologists of the nineteenth century determined that the brain area responsible for sexual appetite — or “amativeness,” as they called it — was located just behind the ears. A telltale lump in the occipital region would reveal its possessor to be unusually lusty. Adjacent lumps divulged more wholesome forms of love: for spouse, family and life itself.

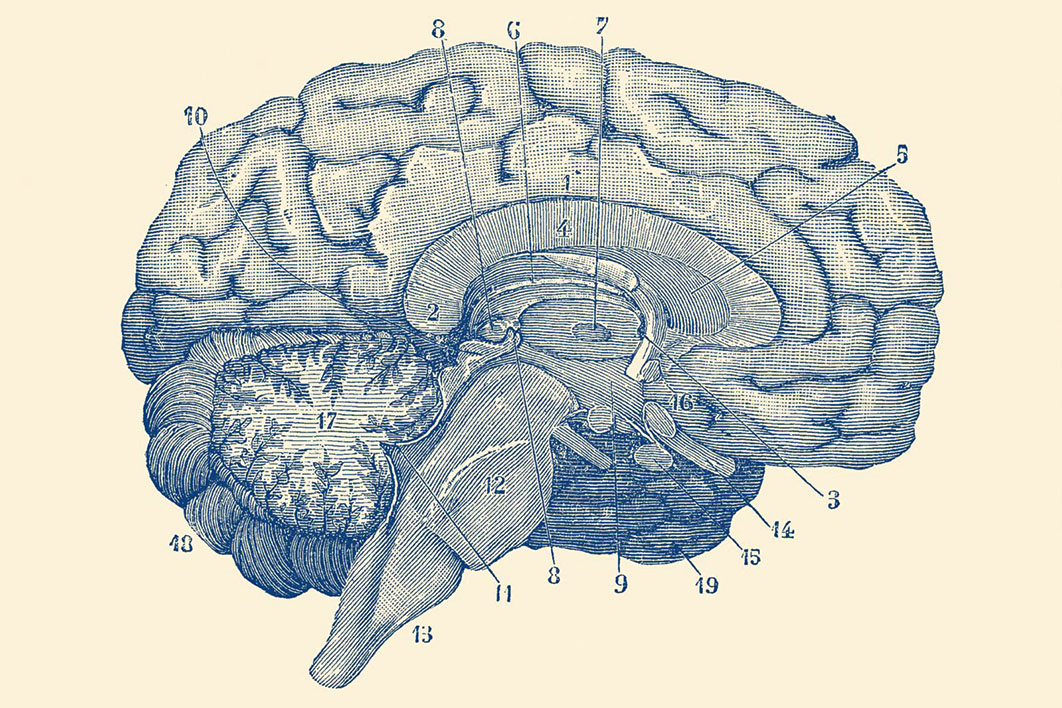

Just how radically wrong this skull-braille was is made radiantly clear in Amee Baird’s engaging book. Bumps on the head don’t allow us to read personalities, of course, but the more basic idea that something as rich and complex as human sexuality might sit in a single brain location is also bunk. Baird, an Australian clinical neuropsychologist, shows that sex is sustained by a complex network of brain regions and pathways, and that alterations to any part of this network can influence sexual response. Ironically, the occipital lobe of the brain, where amativeness was thought to reside, is the one lobe that is out of the network.

The neurological case study has become a popular genre through the work of masters such as the late Oliver Sacks and Harold Klawans. Sacks became famous for his humanising portraits of ordinary people living with extraordinary symptoms. In his case studies these symptoms were rarely sexual, with the exception of Natasha K. from The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat. In her late eighties Natasha became, as she remarked, “frisky,” entertaining carnal ideas about much younger men. She proceeded to amaze Sacks by correctly diagnosing herself with “Cupid’s disease,” a loss of inhibition caused by brain infection resulting from syphilis, which she had contracted seventy years earlier while working in a brothel. Sacks’s message here is that the effects of disease are not invariably negative and do not always cause dis-ease. As Natasha said, in appreciation of her late-in-life rejuvenation, “You’ve got to give it to Cupid.”

Sex in the Brain pays homage to Sacks and even discusses at length one of his later cases, but it has a few important differences from previous case study collections. For a start, the book has a single theme, whereas many such collections are jumbles, occasionally carrying a slight whiff of freak show. Although only a fraction of the cases she discusses are her own, Baird displays an intimate acquaintance with her patients that comes from what she calls “the luxury of time” — the fact that her clinical assessments take hours to conduct, so different from the rapid consultations medical clinicians normally deliver. Unlike many writers of case collections, Baird is a psychologist rather than a medically trained neurologist, and perhaps as a result her chapters mingle case details with discussions of contemporary neuroimaging research. Her psychology background also shines through in her gentle skewering of neurosurgeons’ personalities.

The book’s chapters present an array of sexual alterations and aberrations resulting from brain damage or disease. Baird discusses hypersexuality, apparent changes of sexual orientation, erotomanic delusions of being loved by someone famous, paedophilia induced by brain tumours, the effects of pornography consumption on the brain, and the neural basis of love and sexual pleasure. Brain-based sexual complications associated with Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, dementia and autism are explored, as are the ways that some complications are themselves complicated by gender. (One grumpy and taciturn husband becomes warm, appreciative and romantic to his spouse following a left hemisphere brain injury.) As the book progresses, the reader is introduced to onanistic monkeys, brain structures with interesting names (amygdala and hippocampus derive from words for almond and seahorse), grotesque “cures” for homosexuality, safety-pin fetishes, epileptic seizures that cause orgasms, and orgasms that cause seizures and strokes.

One rather surprising revelation is how often sexual disturbances in the context of neurological conditions result from the treatments rather than the conditions themselves. Some people with Parkinson’s disease have developed sexual excesses following dopamine replacement therapy. Others with epilepsy and other neurological disorders are afflicted by an assortment of sexual disturbances following brain surgeries intended to correct the orginal problem. Baird shows how the unending quest to improve medical treatment has sometimes violated the Hippocratic injunction to “do no harm,” and how when those harms have been sexual in nature they have sometimes been neglected. Too often, she suggests, doctors have failed to ask patients, let alone their partners, about bedroom side effects.

A temptation in neuroscience writing is to reduce the person with a neurological condition to their brainhood and to define the condition as a loss of the individual self. Baird, as a seasoned clinician, is sensitive to how social networks matter as much as neural networks, and shows how the sexual disruptions caused by brain disorders influence a patient’s relationships with partners and family members.

Baird is at her compassionate best when she embeds her patients’ sometimes embarrassing or shameful behaviour in the broader context of their frayed lives and social connections. She writes amiably, accessibly and without titillation. Sex in the Brain introduces a very promising new talent in popular neuroscience and deserves to be widely read. •