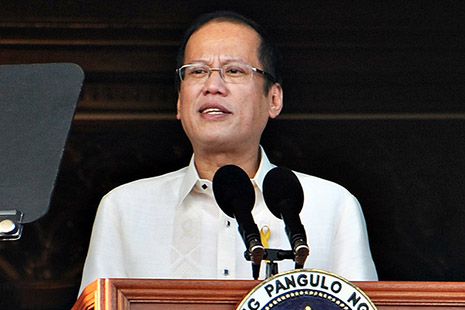

A YEAR AGO this week, on 30 June 2010, Benigno Simeon Aquino III, known as “Noynoy,” was sworn in as president of the Philippines. He came to power with a sense of destiny derived, above all, from his parents. His father, Benigno “Ninoy” Aquino, was gunned down on the tarmac of the Manila airport when he returned to the Philippines in August 1983 to lead the opposition against dictator Ferdinand Marcos. His mother, Corazon Cojuangco Aquino, became the iconic leader of a Yellow Revolution that captivated the world. Thrust into the presidency upon the downfall of Marcos in the People Power uprising of February 1986, she remained a widely respected figure in Philippine politics until her death from cancer in August 2009.

This sense of destiny figured prominently in Noynoy’s inaugural speech last June. “I will not be able to face my parents and you who have brought me here,” he proclaimed, “if I do not fulfil the promises I made. My parents sought nothing less, died for nothing less, than democracy and peace. I am blessed by this legacy. I shall carry the torch forward.”

As everyone in the crowd was aware, the torch of leadership wouldn’t have been in Noynoy’s hands if not for the legacy of his parents. No one seriously considered him a presidential prospect until his mother’s death less than twelve months before the inauguration, when an outpouring of grief and nostalgia propelled him into the race – and eventually into the presidential palace, with the most decisive electoral margin of the post-Marcos years. When the father was assassinated at age fifty, many speculated regretfully as to what more he might have accomplished had he lived on. When the son assumed the presidency at age fifty, after a notably lacklustre record as a legislator, many speculated hopefully that there were many important accomplishments to come.

One year on, opinion polls still register strong public approval and trust ratings for the president. He continues to enjoy a strong mandate for change, generated partly by the record-breaking unpopularity of his predecessor, Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo. While Arroyo came to be viewed as a cynical manipulator intent on empowering and enriching herself at any cost, Noynoy is generally seen as a man with good intentions trying to do right by the country as a whole.

But are good intentions enough? The record of Aquino’s first year is decidedly mixed. A new style of leadership has begun to engender new hopes in the capacity of the country to begin to resolve its deeply entrenched problems. But there is also a strong sense that the achievements to date are insufficient for the magnitude of the country’s multiple challenges. Marites Vitug, a leading investigative journalist, has perhaps captured it best in a recent column addressed directly to Aquino: “Overall, Mr President, you’ve changed the tone of leadership. But that should only be the beginning.”

Campaign promises, campaign divisions

The campaign slogan that led to Noynoy’s decisive victory last year was simple and powerful: Kung walang corrupt, walang mahirap (If no one is corrupt, no one will be poor).

Powerful slogans engender high hopes, and it wouldn’t have been surprising if the president had sought to temper expectations after his election victory. Quite the contrary, he proceeded to set an even higher bar for himself on Inauguration Day by proclaiming a new era in Philippine politics: “No more turning back on pledges made during the campaign… No more influence-peddling, no more patronage politics, no more stealing… no more bribes. It is time for us to work together once more.” Most of all, the speech is remembered for its denunciation of wangwang, “the siren-blaring escorts of those who love to display their position and power over you.” Symbolic though it may have been, this promise to abandon disruptive presidential motorcades resonated deeply with a population that was clearly ready for change. As the mother in 1986 had declared the end of the nightmare that was Marcos, so the son in 2010 pronounced “the end of a regime indifferent to the appeals of the people.”

Setting forth to translate campaign promises into concrete achievements, the new president appointed a cabinet that includes many highly capable figures with a demonstrated commitment to reform. Many are leading figures from the business community and the legal profession, but others come from movements advocating social change and new forms of politics. Economic management is led by finance secretary Cesar Purisima, the former head of a leading accounting firm, and his assignment includes cleaning up the notoriously corrupt agencies of internal revenue and customs. The anti-poverty effort is led by social welfare secretary Dinky Soliman, whose roots are in reformist civil society groups. Both Purisima and Soliman served in the early Arroyo administration, but resigned in protest after an electoral scandal was revealed in 2005. Their respective portfolios are given major support from budget and management secretary Florencio Abad, a leading figure in Aquino’s Liberal Party and a skilful ex-congressman who formerly served as agrarian reform secretary in the first Aquino administration.

That administration, in power from 1986 to 1992, is remembered for its rather jarring combination of purity and sleaze. Mrs Aquino had a reputation for incorruptibility, as if she were on a pedestal above the fray, but below her was a throng of Palace insiders (and would-be insiders) renowned for deal-making and intrigue. Most notorious was her own brother, Jose “Peping” Cojuangco, who consolidated the administration’s political fortunes throughout the archipelago by cutting deals with a wide assortment of local patrons and bosses – some of whom had less than obvious allegiance to the ideals of People Power democracy that had put Mrs Aquino into the Palace in the first place.

Noynoy seems to have learned from the negative example of his mother’s administration, and there is little evidence of an unduly influential role for his four sisters (even for the youngest, Kris, a wildly famous movie star with years of experience in grabbing the headlines). While he appears not to be repeating the mistakes of the past, Noynoy’s Palace has nonetheless displayed major problems of a different nature. There are at least two primary centres of power within the administration, and the media regularly speculates as to which is dominant within particular spheres of political contention. President Aquino seems to have no strong desire to bring peace between the warring factions; should such a desire indeed exist, his efforts as peacemaker have been notably unsuccessful.

These divisions date back to the presidential campaign of 2010, when many supporters of Noynoy Aquino proved less enthusiastic about his vice-presidential candidate, Manuel “Mar” Roxas II. Both were on the Liberal Party ticket, and both have a strong family heritage in the party stretching back to early postwar years. Roxas’s grandfather, Manuel Roxas, was the first president of post-independence Philippines from 1946 to 1948. His father, Gerry Roxas, was a party mate of Ninoy Aquino in the years before Marcos declared martial law in 1972. The younger Roxas was in fact a contender for the presidency in the lead-up to the recent elections, but stepped aside in favour of Noynoy after the death of Mrs Aquino in August 2009. He recognised the powerful swell of popular support in favour of a party mate (and senatorial colleague) who was seen as the rightful claimant to the Aquino mantle of leadership, and contented himself with the quest for the second-highest post in the land.

Because the Philippine electoral system enables voters to cast separate preferences for president and vice-president, support for Aquino did not automatically translate into support for Roxas. Philippine politics is notorious for a high degree of ticket-splitting at the top, exacerbated further by political parties’ generally pronounced lack of coherent policy programs. Several months prior to the May 2010 elections, Mar Roxas was the odds-on favourite to grab the vice-presidency, enjoying an even greater lead over his rivals than did Noynoy. But his margin in the polls decreased as the election drew closer, partly because of a strongly anti-Roxas movement led by two politicians with their eye on capturing the top post in the next presidential election of 2016. (In essence, the anticipation of competition in 2016 already influenced electoral dynamics in 2010 – particularly given that the winner in 2010 is constitutionally ineligible to serve a second six-year term after 2016.)

One of those two politicians was Jejomar Binay, a long-time mayor of the country’s premier financial centre and a former ally of Corazon Aquino. In the 2010 elections, however, Binay was the vice-presidential hopeful in the same party with presidential candidate Joseph Estrada, Noynoy Aquino’s leading rival. A former movie star, Estrada was elected to the presidency in 1998 but ousted three years later via a second People Power uprising in 2001. After being convicted of the crime of plunder and serving part of his sentence, he was eventually pardoned by Arroyo. He and Binay then teamed up for the 2010 elections, in a partnership of sheer convenience that soon became badly frayed. Estrada’s main goal was a respectable run that would help to rehabilitate his name and his family’s political fortunes (and he did indeed finish with 26 per cent of the vote, second only to Noynoy’s 42 per cent). Binay’s main goal, however, coincided precisely with that of Roxas: a term as vice-president that could propel him to the presidency in 2016. Given his strong historical ties with Corazon Aquino, many Noynoy supporters were inclined to give him their support; this was actively encouraged by Binay stalwarts, who urged voters to support a split-ticket they dubbed “Noy-Bi.”

Binay came from behind to narrowly defeat Roxas, and the tensions between the two rivals remain strong to this day. At the end of June 2011, Roxas will move out of his role as Palace adviser and assume a new and potentially high-profile role as secretary of transportation and communications. Binay serves concurrently as head of the Housing and Urban Development Coordinating Council, and has recently registered even higher public approval ratings than the president (83 per cent versus 71 per cent, according to a June 2011 poll by Pulse Asia).

The divide in last year’s campaign continues as an important breach within Aquino’s administration, but it would be a gross simplification to capture the dynamics of Palace factionalism through such a simple binary. Political divides in the Philippines are ever-shifting, uniting former rivals and dividing former allies in a continual process of alignment and realignment almost entirely divorced from coherent positions on policies or programs. Philippine politics is notoriously personalistic, and the current president has frequently been criticised in the press for the range of top appointments that seem to be heavily influenced by personal ties. Both in the Palace and in major agencies, critics charge, one can find a range of kaibigan (friends), kaklase (classmates) and kabarilan (shooting buddies, reflecting Noynoy’s well known love of guns). The undersecretary of the interior in charge of overseeing the national police force, for example, is said to be a kabarilan who owns a chain of gun shops. The actions of another kabarilan, the head of the Land Transportation Office, has recently been a source of controversy in the news.

In sum, the administration of Noynoy Aquino defies easy characterisation. On the one hand, there are indeed many highly capable members of the cabinet intent on implementing important measures of reform within their respective departments. Within the Palace, on the other hand, there is a deep divide between camps that have a deep mutual disdain rooted in the 2010 campaign. This intersects with a countless range of other political rivalries, ever-evolving within a complex web of personalistic ties that not infrequently lead straight up to the president himself. Amid this study in contrasts, one gets the sense that presidential supervision is not particularly intensive or consistent; whether cabinet secretaries are performing strongly or weakly, they pretty much seem to run their own shows.

Relations between the Palace and the House of Representatives are a bit more straightforward. Although the Liberal Party and its allies had only a small minority of seats in the immediate wake of the elections, they quickly built a coalition majority through the time-honoured Philippine practice of “turncoatism.” A veteran politician who had recently switched parties was chosen as Speaker, with the understanding that he would assist in manufacturing a coalition majority for the Liberals. Lured by the advantages of proximity to the administration, and thus to the patronage resources it has to dispense, members of congress switched parties by the dozens. The Liberal Party has now greatly expanded its numbers, albeit with many new members who have come on board purely for the sake of convenience. They are bound together not by programs and policies but rather by pork and patronage. In the Senate, where a mere twenty-four members are each elected by a nationwide constituency and thus accorded greater individual stature, cobbling together a majority is a much more tedious and expensive proposition. With considerable expediency, however, the administration has managed to develop workable arrangements.

Corruption and poverty: progress to date

With a campaign slogan that focused on corruption and poverty, the administration can fairly be judged on its achievements in these two realms (setting aside the larger question of whether fighting corruption is indeed the optimal means of reducing poverty). The picture is once again mixed.

Some initial initiatives to curb corruption in key agencies, most importantly in the revenue sphere, have yet to bear fruit. Meanwhile, recent major corruption scandals in the military– dating from past acts but only recently revealed–suggest that the rot may be spreading rather than receding. The most prominent anti-corruption measures, not surprisingly, have been the current administration’s efforts to expose what it alleges to be the highly corrupt behaviour of the former administration. Aquino supporters were delighted at the May resignation of the Arroyo-appointed ombudsman, widely viewed as a major obstacle to bringing Arroyo administration figures to account. Her departure came after an overwhelming House vote in support of impeachment, and she was facing the prospect of an impeachment trial in the Senate.

Critics, however, point to the continuing lack of corruption cases being lodged against major figures in the Arroyo administration. Former president Arroyo sits as a member of the House of Representatives, and can continue to count on the support of a Supreme Court that she largely appointed. The longer it takes for prosecutors to lodge cases against the Arroyos and their associates, the louder this criticism will become. But it will not be easy to prosecute the former administration, not only because of its ongoing influence but also on the evidence of past trends. To wit: a quarter-century after the demise of Marcos’s kleptocracy, his family and leading cronies are not only free but prospering (with Ferdinand’s widow Imelda in the House, the son in the Senate, and a daughter governor of Marcos’s home province).

With anti-poverty measures struggling to keep pace with the country’s rapidly growing population, widespread poverty remains among the greatest challenges faced by the Philippines. While there is no consensus on land reform or broader issues of asset reform, particularly given that the president’s family owns a giant sugar estate in central Luzon, the administration has promised to lift revenue and increase government spending on education and health services for the poor. Attention has focused primarily on a dramatic expansion of the conditional cash transfer program, through which extremely poor families are given cash grants in exchange for meeting certain conditions (for example, keeping their children in school). The administration has also given its support to a Reproductive Health Bill that would enhance the access of the poor to artificial birth control. Although the bill has garnered overwhelming public support as measured in opinion polls, the vociferous opposition of the Catholic Church will present major obstacles to its eventual passage.

Other challenges ahead

As important as the alleviation of corruption and poverty are to the future prospects of the Philippines, they are only two of the country’s many deeply pressing concerns. A lack of employment opportunities encourages some ten million Filipinos to head overseas for work; in turn, the economy as a whole is dependent on overseas remittances, which bring roughly $18 billion per year back to the Philippines. The quality of the public education system has declined steeply in recent decades. As highlighted by the killing of eight Hong Kong tourists in an August 2010 hostage-taking fiasco, the police force is inadequately trained. Environmental degradation has been massive and the country faces enormous risks arising from climate change; both factors heighten the country’s longstanding vulnerability to natural disasters. The secessionist conflict in Mindanao is four decades old and still unresolved by what has come to be known as a permanent peace process. A similarly longstanding communist insurgency continues to be fuelled by deep socioeconomic disparities. And the central government remains unable to exert effective control over the national territory, particularly where local bosses maintain their own private armies (most famously the Ampatuan family of Maguindanao, currently on trial for the brutal massacre of fifty-seven people in late 2009).

At the same time, the Philippines faces growing security challenges amid an increasingly volatile regional environment. Tensions are once again mounting in the South China Sea, where multiple countries have overlapping territorial claims. As China flexes its muscles, the Philippines is bringing forth two second world war–era vessels for joint naval exercises with the United States.

From leadership change to institutional reform

When he became president, Noynoy Aquino promised a new style of leadership. “The first step,” he said, “is to have leaders who are ethical, honest, and true public servants.” He pledged not only to “set the example” himself but also to hold similarly high standards for those who join the government.

While there has been a welcome shift in intentions and many officials are of high calibre, the changes thus far are dramatically dwarfed by the challenges that the country continues to face. At the most basic level, there seems to be a lack of strong strategic direction to guide the administration as a whole – even if many individual cabinet secretaries do seem to be executing clear goals within their specific areas of responsibility. There is also seemingly little effort to mend the administration’s deep divisions, which are further complicated by a dense web of personal ties that are at times directly connected to the president.

More fundamentally, as the president himself has acknowledged, a change in leadership style is only a “first step.” An essential element of longer-term success will be a concerted effort to reform the Philippines’ increasingly beleaguered political institutions. While the president spoke with passion in his inaugural address about the need for a new type of leader, he did not articulate any vision of institutional change. This will require difficult and protracted effort, given the longstanding weakness of basic institutions inherited from the American colonial regime as well as the highly personalistic character of the polity. But it must be done if challenges are to be met. The president needs an effective bureaucracy, something that his predecessor Fidel Ramos recognised when he stated plainly – during his presidency in the 1990s – that the bureaucracy is the weak link in Philippine development. And the president needs an effective, coherent and well-institutionalised party if he is to sustain his ambitious goals into future years. The building of such parties has received little attention from any of his predecessors in the Palace.

Looking forward, we can anticipate mounting challenges of governance. There are many reasons for this, but a focus upon population growth is sufficient to make the point. Thirty years ago, when Noynoy and his family were in exile in Boston, the population of the Philippines was forty-eight million. It is now an estimated ninety-five million, and three decades hence (in 2040) it is projected to reach 140 million. As the country grows and its problems become more complex, a focus on leadership alone is woefully insufficient. If success is to come, and if the torch is to be carried forward beyond the current administration, a new and cleaner style of leadership needs to be accompanied by concerted attention to reforming the country’s key institutions.