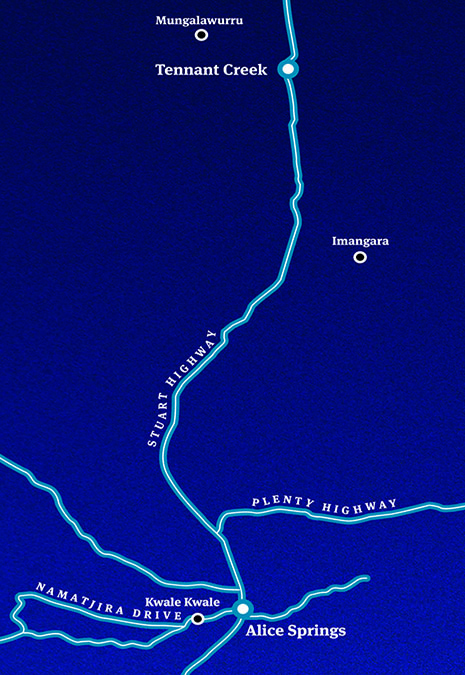

THE average house in a remote Indigenous community uses about a third of the power consumed by a suburban home, is six times more prone to overcrowding, and probably doesn’t have a home internet connection. Among the rare exceptions – at least when it comes to the internet – are twenty houses in the small communities of Kwale Kwale, Mungalawurru and Imangara in central Australia. With federal funding, these households have been given computers, internet access and training, and receive regular visits and advice.

When the project commenced, there were fears that the computers would never last. This is a harsh environment, hot and dusty, and homes are typically crowded and a long way from repair shops. Cultural factors – including mobility and attitudes to property ownership – added an extra layer of complexity. And the fact that very few households had purchased computers and taken out internet subscriptions of their own accord was seen by some critics as proof that, at best, home internet was not the preferred means of online access or, worse, it was inappropriate or unviable.

But the experience so far has been more encouraging. Taking into account equipment failures, loss and damage, seventeen of the twenty computers installed by early August 2011 were still operational at the end of April this year. During that period, researchers from the Centre for Appropriate Technology, who are leading implementation and maintenance, travelled out to the communities to provide training and upkeep. We went along on some of these visits to document how the project was going.

What has become increasingly apparent is that the digital divide is more complex and dynamic than cultural differences or inadequate infrastructure can explain. Unlike many people in urban and regional Australia who don’t use the internet, residents in these three communities suffer from double remoteness: they don’t have easy access to either physical or digital resources. There are some digital resources in communities, it’s just that they are scarce: people are using mobile phones when and where they can; some shared facilities provide computer access; and some households and communities have televisions and entertainment systems.

Just as importantly, when we look at people elsewhere in Australia who don’t use the internet, a substantial number turn out to be “proxy users.” Many are older, and while they don’t use the internet themselves, they can ask family or friends to do things online for them – buy air tickets, for example, or complete an online form for a government agency. In remote Australia, where there are significantly fewer active users across generations, there are correspondingly fewer proxy users.

Some people contend that the digital divide will fix itself as network and equipment costs fall and the internet becomes more and more a part of daily life. They argue that since the number of non-users nationally is now relatively small – around 14 per cent of the adult population, mostly in older age groups – a dramatic social divide no longer exists between the digital haves and have-nots, and that the benefits of being online will eventually attract almost everyone.

But the problem is actually more intractable, and not just in remote regions. Although the number of non-users across Australia is declining, it appears to be doing so increasingly slowly. The pattern is the same in other Western countries. We’re not sure why, and projects like the National Broadband Network, or NBN, may change the trend. But if the growth in internet access stalls then this will have serious implications, particularly in an environment in which both public and private service providers (including the company managing the NBN) rely heavily on the internet itself as the vehicle to promote their business.

As the group of non-users gets smaller, they are likely to become more seriously disadvantaged. The NBN – and high-speed broadband more generally – will drive a wave of new applications across most areas of life, transforming Australia’s service economy in fundamental ways. Those who are not connected in 2015 may be fewer, but they will be missing out on far more – in education, health, government, commerce, communication and entertainment. The costs will also fall on service providers forced to keep supplying expensive physical and face-to-face services to this declining number of people. This will be particularly significant in remote communities, where health consultations and evacuations by flying doctors, nurses and allied health professionals could potentially be reduced through e-health diagnostics, and where Centrelink still regularly sends teams out to communities.

Being connected also means different things for different people. Studies elsewhere show that access and connection, on their own, are not enough to lift people’s participation in education or the economy. Well-educated and relatively well-off internet users take advantage of new technologies much faster, and use them for a wider range of purposes. If there are no jobs where you live then you are unlikely to use the internet to search for work. But once people have a computer and a connection, many of them do begin to find additional uses for them.

In one of the three communities, for instance, a senior woman asked us to show her how to check her BasicsCard balance online. Income quarantining, first introduced in remote Indigenous communities under the Northern Territory Intervention, allocates a portion of a family’s welfare payments to a debit card that can only be used for essentials such as food and clothing. “I don’t want to have to ask the woman at the store to check it for me anymore,” she told us. After a lengthy wait on the Centrelink helpline – in the freezing wind on the community’s only telephone – we managed to set her up with an online account and went into her house to show her how to log on. The satellite internet speed was so slow that the site’s security system kept locking us out (these communities have not yet moved to the NBN Interim Satellite Scheme, which provides faster internet); and once we did get in, the website was unnecessarily complex. Regardless, this woman was willing to try to navigate the site in order to have some level of financial control, even if it was only to know how much money was available that day.

We witnessed a similar enthusiasm for online banking and bill payments in another community, where residents have to travel ninety kilometres to conduct basic transactions if the public phone is not working (or when their phone cards run out). Since getting computers and the internet, women have begun using eBay to buy kids’ toys, DVDs and clothes, items that can be expensive in remote communities if they are on sale at all. One woman asked us to upload a learn-to-type program to her computer as she was spending up to three hours a day on chat sites with friends who live in other communities and towns.

On any given day during that period, around a third of households were connecting to the internet. When they were asked recently if they would pay to keep the internet, most residents said they would, and valued that access at between $30 and $100 a month.

TO DEAL with the digital divide so evident in these communities, the federal government’s recent Regional Telecommunications Review proposed a number of useful steps, including digital skills training. The review also recognised that we need to know more about the uneven distribution of access in remote Indigenous Australia. But to improve the situation, we also need to know more about why current levels of access are so low.

Nobody uses the internet because the government or Telstra says it’s a good idea. People are driven to connect to the internet by their social networks. As more people you know go online – whether they are children, friends or colleagues – the more likely you are to try it yourself. Since the introduction of computers last year, this pattern is playing out in the communities of Kwale Kwale, Imangara and Mungalawurru. The power of social networks, together with low cost and accessibility (where mobile coverage is available), also explain the extraordinary popularity in the bush of services like airG, a mobile chat service designed for mobile devices. But the network effect can also help us understand why adoption rates can sometimes get stuck at very low levels: when online contacts are scarce then the network is less rather than more valuable to users, and the technology less likely to be used.

This is why it seems difficult to reach that critical mass of users sufficient to draw further groups of people online in remote communities; and it is also why these communities are likely to take up internet services in ways that reflect their own society and culture rather than following patterns set elsewhere. But once people do have a device and a connection, another dynamic may apply, and a kind of economising can begin to encourage a broader range of uses. The device you acquired to create and listen to music may turn out to be useful for low-cost messaging as well.

The NBN model of fixed connections to homes has been criticised on the grounds that it fails to grasp both the dynamism of the mobile internet and the complexity and diversity of household structures. In the bush, mobiles are often seen as more flexible and easy-to-adopt, accommodating more readily to the way people move between households and in and out of towns.

We don’t yet know how household connections in remote communities can be best designed and managed (although we are getting closer). The underlying concept of the NBN – public wholesale provision of a privately consumed service – may still be the most workable model. It’s no criticism of shared resources such as public internet centres to suggest that private ownership of computers or other devices might have a valuable place in an evolving domestic digital ecology in remote Indigenous households.

Household connections shouldn’t simply be seen as expensive substitutes for mobile access or for shared facilities, and in the many remote places where there is no mobile coverage and shared centres are difficult to staff they may be the only option. They can also help people share a connection, and make more and cheaper use of their mobiles through wifi. But the most important thing that household connections offer is a degree of autonomy and private control over communications that the rest of Australia takes for granted. •