Too often tales of exploration are told only from a whitefella perspective. But as this story of a roving zoologist reveals, “the observed” were observing closely when the American–Australian Scientific Expedition descended upon Arnhem Land in 1948.

— Martin Thomas

On Croker Island, just a short canoe trip from the Cobourg Peninsula in northwest Arnhem Land, a story has long been told about an unexpected visitor. His name, if ever it was known, is now forgotten. What is remembered is that he was a white man from America and that he possessed unusual powers. No sooner had he arrived than he began to roam the bush at night, shooting or capturing possums, bats, bandicoots and other small animals. Whether he told the local people what his occupation was, or whether they deduced it themselves, is unclear. His fearlessness, his superb marksmanship and other, more mysterious, traits left them in no doubt that the visitor was “a real scientist.”

After he returned from his nocturnal rambles, the man skinned the creatures he had killed. Then, to the amazement of onlookers, he stuffed the empty skins with padding and sewed them up. The late David Minyimak was one of several elders who spoke with authority about the stranger. After all, he had paddled him around in a dugout canoe. For Minyimak, the ability of the American to alter the dead was branded in memory. They “looked like they were alive,” he said of the stuffed animals. In the words of another old man, it was “like they had a real body.”

At the time of the stranger’s visit, the Iwaidja-speaking people had not yet moved to Minjilang, as the mission on Croker Island is known. In those days, they still lived on or near their ancestral estates on the mainland. Information about the man did not circulate outside the community until the first decade of the present century when it was recorded on video as part of a cross-cultural research project. Close collaboration between Bruce Birch, a linguist, and several Iwaidja speakers resulted in the English translation quoted here.

For David Minyimak, Charlie Mangulda, Khaki Marrala, Archie Brown, and others who recounted this important episode in their local history, the passage of time was seldom measured by numbers or dates. Instead, they used broad temporal signposts, recognised by the entire community. There is, for example, “Macassan time,” the era when voyagers from the port of Makassar on the Indonesian island of South Sulawesi used to come annually, trading and gathering the sea slug known as trepang, which would eventually be taken to China where it is considered a delicacy. Other well-known epochs include “wartime” (the second world war), “mission time” (the time of the missionaries) and “Whitlam time” (the era in the early 1970s when the prime ministership of Gough Whitlam introduced pro-Aboriginal policies that changed their lives).

Map of base camps and other locations visited by the 1948 American–Australian Scientific Expedition to Arnhem Land. National Geographic, December 1949

Everyone agrees that the visit of the American scientist occurred “after wartime.” In those days, many of the northwest Arnhem Landers were living at Jamarldinki on the tip of Cobourg Peninsula. The maps made by Balanda — the white Europeans — refer to the place as “Cape Don.” After a lighthouse was constructed there in 1917, Aboriginal people began to camp nearby, forming a semi-permanent settlement.

It was there at Jamarldinki that they first encountered the American. He was so different from the men who ran the lighthouse and from all the Balanda they had previously met. For that reason, they observed him with special attention. A small but well-remembered detail is that when he returned from his night-time activities, he had scarcely a mark on his pale outfits. This struck the Aboriginal witnesses as strange because the scrub and grasslands were heavily charred as a result of the seasonal burning. Another strange thing about the visitor was the manner of his departure.

When he left the community at the lighthouse, he walked eastwards along the peninsula and then south to Oenpelli, where Anglicans oversaw a mission station. Although the distance exceeds 200 kilometres, he is said to have walked it in just two days.

The more fantastical elements of the story suggest that the local mob were at something of a loss in trying to understand this peculiar individual. In their efforts to make sense of him, they did what most of us do when confronted with the inexplicable: we try to bring it into focus by reading it through our own cultural lens. When they did this, the people at Jamarldinki came to the conclusion that the scientist was a marrkijbu. This is an Iwaidja term that translates as “shaman,” “clever man” or “man of high degree.”

The marrkijbu is said to possess “a heightened ability to manipulate aspects of both the natural and the supernatural realms.” He has a “special power” to “heal, or equally, to harm another.” A figure of heightened wisdom and judgement, his “clever” attributes can include the ability to foresee future events. For Aboriginal people of that era to identify an affinity between scientists and clever men is anything but far-fetched. In their respective cultures, both types of expert are reputed to have refined knowledge of, or control over, their natural environments.

A 1955 issue of National Geographic gives insight into the origins of the story about the American clever man. That year, the Geographic ran an article titled “The Incredible Kangaroo” by David Horn Johnson, a PhD in mammalogy who worked as a curator at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC. In this capacity, he was sent to Australia in early 1948 as a member of the American–Australian Scientific Expedition to Arnhem Land. While the article is about kangaroos and says very little about the places and people that Johnson encountered as an expeditionary scientist, an earlier National Geographic article by Australian photographer, amateur anthropologist and expedition leader Charles Mountford describes how Johnson visited the Cobourg Peninsula where he made a “lonely walk through the ‘Never Never.’” Along the way, he collected and pres erved zoological specimens for the Smithsonian’s natural history collection.

Monitored and analysed: David Johnson performing taxidermy during the Arnhem Land Expedition. Charles Mountford/Mountford–Sheard Collection, State Library of South Australia

There are so many affinities between Johnson and the Clever Man that there is no real doubt the story was inspired by Johnson’s visit in 1948. While in Arnhem Land, Johnson carried out a survey of mammals, concentrating on marsupials. His time in northwest Arnhem Land began at Cape Don, which he reached by boat. Like the man remembered in the story, he travelled entirely on foot. He did walk the full length of Cobourg Peninsula and onwards to Oenpelli — something that no white man had done in living memory. However, in contrast to the ultra-marathon attributed to the Clever Man, Johnson took twelve days to complete the journey.

The Aboriginal and Balanda sources agree on several fundamental points. The scientist was a highly competent backwoodsman and he wore pale safari outfits. His own colleagues were struck at how he kept himself so clean. Johnson, like the Clever Man, was an ace marksman and highly adept at tracking wildlife. Most significantly, he travelled with surgical instruments, chemicals, needles and a supply of thread that enabled him to taxidermically preserve specimens as he collected them.

Johnson’s scientific report on the expedition makes only brief mention of his time on the peninsula, although it does praise the hospitality of the chief lighthouse keeper and acknowledge “a great debt of gratitude to many aborigines, some never learned by name, who for little or no reward collected specimens, showed me where to look for different species, guided me on walkabout trips, and tried earnestly to impart some of their profound knowledge of animal life.”

It is disappointing that Johnson did not say more about these interactions, but compared to the reports compiled by some of his colleagues, he is generous in his acknowledgement of the traditional knowledge that informed his fieldwork. There is no evidence that he had any idea of how closely he was being monitored and analysed by the locals. Johnson died in the United States in 1996 and never heard the story inspired by his visit to the peninsula.

The Smithsonian mammalogist appears briefly in a documentary film, produced by the National Geographic Society. There is even a scene in which Johnson performs his taxidermic “magic” for the camera. This sequence seems to have been shot on the mission at Oenpelli, where the meaty spectacle of carcasses being stripped of fur again aroused interest, and not only from a human audience. The local dogs, ubiquitous in Aboriginal camps, milled around the visitor, as did great swarms of flies, harassing him while he worked.

Sixty-two years after the film was shot, the late Joy Williams, the traditional owner of the Adjamarduku homeland on Croker, invited me to visit the island with a videographer and sound recordist. Enabled by Bruce Birch, who interpreted the Iwaidja for us Anglophones, we camped on Joy’s ancestral country and studied the American clever man narrative in further detail. In the process, we showed the historic film to the key tellers of the story. They scrutinised it knowingly and everyone agreed that this was the American scientist of whom they had spoken many times. Indeed, a few seemed to regard it as something of a “told you so” to those naysayers in their own community who had doubted the validity of the story.

Important as they are, the consistencies between the oral account and the textual evidence are less revealing than the divergences, which take us into the most controversial parts of the narrative. A more sinister face of the Clever Man became apparent when he visited a forested area on the peninsula called Madirrala. This is near Port Essington, a fabled site in the history of Australian exploration, for the British garrison that was stationed there for a few years was the end point of Ludwig Leichhardt’s first expedition in the 1840s. These days, it is an evocative ruin. For the local people, Madirrala is a site of extreme danger because it is occupied by a type of hostile spirit known as a yumbarrbarr — a giant creature that eats human flesh. A yumbarrbarr lives inside a tree that is never far from the physical remains of people it has eaten.

Ordinary folk are understandably terrified of these homicidal tree spirits. Not so the clever men of the area who “have the ability to “tame” yumbarrbarr, and to use them as an extension of their own power.” David Minyimak was with the American at Madirrala when the scientist told him that he had seen a “big man” near a tamarind tree and that he “would have liked to have captured him,” but decided not to because of his size. Minyimak and his kinsmen inferred that the scientist had seen a yumbarrbarr. Merely to suggest that he could capture such a foe was deemed extraordinary, and it provided further confirmation that the visitor had supernatural powers.

The towering David Johnson (right) inspects a stuffed wombat being held by a museum official in Melbourne prior to the expedition. On the left is the expedition botanist Raymond Specht. Charles Mountford/Mountford–Sheard Collection, State Library of South Australia

Like several other Clever Man episodes, this part of the story is less easily reconciled with a “factual” account of Dave Johnson’s tour. It does, however, say a great deal about the way ideas and knowledge transit between cultures in a process that is so often pitted with invention and misunderstanding. That said, the story has its own deep logic, being founded on close observation and analysis. The association between the scientist and the yumbarrbarr was undoubtedly reinforced by the fact that Johnson himself was extremely tall.

In his examination of the story, Bruce Birch points out that the Cobourg Peninsula has long been inhabited by sambar deer, introduced from Asia. He asks whether Johnson, who had encyclopedic knowledge of animal taxonomy, could at some stage have suggested to Minyimak or other people camped at the lighthouse that he shoot one for food. Johnson’s scientific report does mention “Indian sambar deer” (Rusa unicolor) in a discussion of introduced mammals. So it is possible that he used the term when speaking to the people he encountered. Was “Indian sambar deer” in an American accent misheard as “yumbarrbarr”?

While that question, like so many issues raised by the story, must remain unanswered, the suggestion in the narrative that the scientist derived both power and authority from killing, manipulating and arresting the decay of the bodies of his prey is highly salient. In the eyes of the beholders, his taxidermy blurred the accepted boundaries between the living and the dead. This led them to draw parallels between his empowerment as a scientist and the powers claimed by local shamans. As an assessment of Johnson, a man of knowledge and erudition within his own society, the story is shrewd.

The business with the yumbarrbarr presages the darkest of all the deeds attributed to the American clever man. No local man or woman would have dreamed of doing what the scientist is alleged to have done during his long walk to Oenpelli. The locality where this occurred was Dilkbany, another site of ancestral power, in this instance resulting from the presence of human ghosts. Their concentration at the site requires some explanation.

The traditional mortuary rites of western Arnhem Land are long and complex, sometimes lasting several years. The body of the deceased is subject to various forms of ceremonial treatment and is likely to be shifted on a number of occasions. In the last phase of these observances, the dry and fleshless bones are painted with ochre, wrapped in paperbark, and interred in a rock shelter located within the ancestral estate of the deceased. This final act involves much more than the physical placement of the bones. As well as being a formalised expression of grief, it is about emplacing and orientating the deceased so that he or she is secure in the process of becoming a dead person within their home territory. In death as in life, people inhabit the country they were born to.

While spirits are not exactly tethered to the physical remains of their living selves, they remain closely connected with them. The bones are tangible evidence of the ancestor, perceptible to both the living and the dead. Despite the turn towards Christian burial, encouraged and at times enforced by missionaries, traditional mortuary rites were performed for at least some individuals until well into the twentieth century, especially if the deceased were considered to have been exceptionally “strong” in their culture. The extended history of these practices means that certain caves and fissures in the rock have, over centuries, become large storehouses of the dead. Dilkbany is one such location.

The narrator of the Dilkbany section of the Clever Man story was Archie Brown, whose own grandfather was at the centre of the sad events recounted. As Brown told it, at this stage of his southward journey the American was walking along a well-defined trail, resulting from activity associated with a nearby sawmill. Archie Brown’s maternal grandfather, a member of the Alarrju clan, had died some years earlier. His name was Marrarna and according to custom, his bones were placed in a rock shelter at Dilkbany. The story recounts that when the Clever Man approached this place, he noticed the opening in the rock where the bones were housed. Marrarna (which is to say his spirit) happened to be standing outside the cave at that moment. Then, as the stranger approached, he slipped inside. The American must have glimpsed Marrarna for he immediately picked up a rock and threw it inside the cave, forcing the dead man to come out. As soon as he did so, the American grabbed him and put him in a bag.

“He carried him off,” said Archie. “It was his spirit that he took. It seemed like a spirit, but it must have been the actual body itself. They headed off. He put him in the bag and they headed for Gunbalanya.”

At Gunbalanya, as Oenpelli is more often known to the local people, the American met with his Balanda friends who were staying there. But he never told them about Marrarna, who remained imprisoned in the bag. The American then left Arnhem Land, travelling first to Darwin and then to his home in a city in America, where he was reunited with the people who Archie Brown referred to as his “bosses” or the “ones who sent him here.” Only then did he remove his captive from the bag. The bosses or other American people who were present took “lots of photos” at this moment. As they did so, they documented an astounding transformation.

A staged photograph of the expedition camp at Gunbalanya. National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution

“At that point,” said Archie, “my grandfather had already undergone a change. He’d assumed the body of a living man. He no longer resembled the bundle of human remains, the way we put them there. He stood there as a living person… He spoke to all of them. ‘It’s me. It’s me. I’m the one you captured. You took me.’ He identified himself. ‘I’m Marrarna.’”

Then, in a sort of incantation, Marrarna uttered the names of his children and close relatives, as well as that of Paddy Compass Namadbara, the famed bark painter, widely regarded as the last great shaman of the region. That Marrarna should mention him is not surprising since Namadbara, while not his biological relative, was the adoptive or “classificatory” son of Marrarna according to the local kinship system. Brown recalled that the bosses in America were well pleased with the work of the American scientist and they paid him handsomely. He made “lots of money” from the capture of Marrarna.

The Clever Man story draws a connection between the scientist’s ability to make dead animals look lifelike and the rejuvenation of Marrarna. In so doing, it points to the range and limit of the scientist’s powers. There is, after all, a huge contrast between the stuffed animals the scientist tried to reanimate and the vital life force who leaps from captivity to assert his name, his kin relations, and thus his very existence. “It’s me… I’m Marrarna.”

Although displaced from his country (a horrific prospect for Arnhem Landers), Marrarna exerts power at this moment. Indeed, we could rightly think of it as a display of cleverness, for it transpires that in life Marrarna was himself a clever man, or marrkijbu.

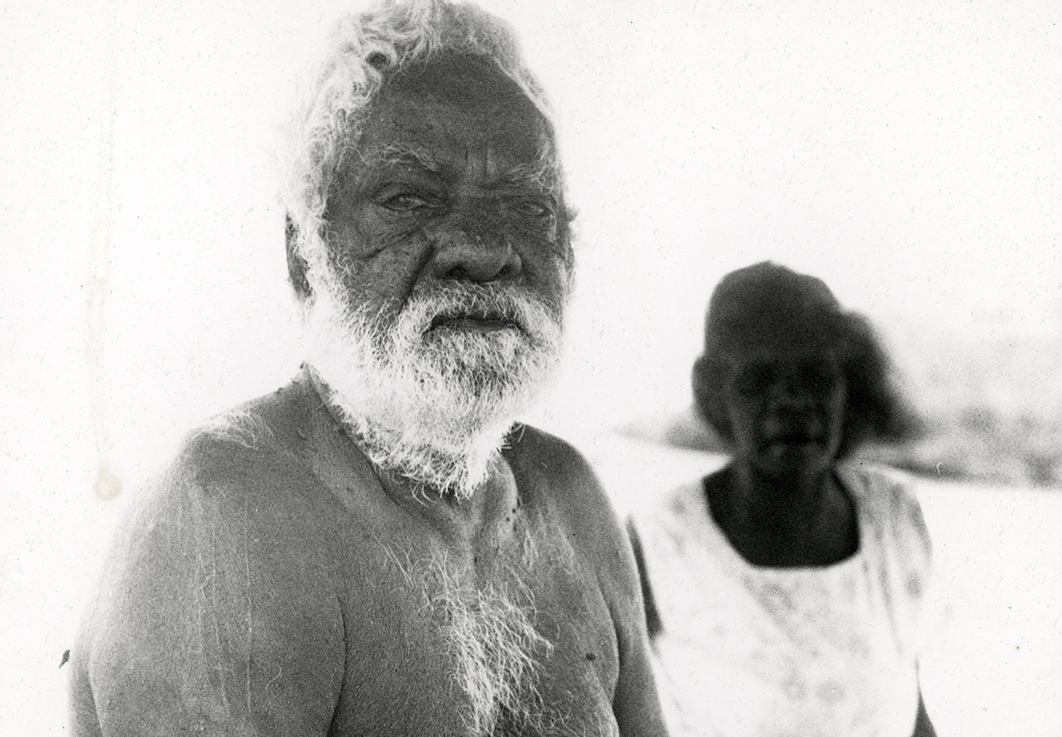

An esteemed painter, Paddy Compass Namadbara was widely regarded as the last great clever man of west Arnhem Land. Namadbara and his wife Rhoda were photographed at Mountnorris Bay in the 1970s by the rock art scholar George Chaloupka. Courtesy of Ian White

The Clever Man story perceptively links the gathering of zoological specimens and the scientific collecting of human remains. In its artful and incisive way, the story fills the gap between the mysterious visit of the scientist and the appalling discovery at some later date that Marrarna’s bones had been stolen from their final resting place.

The belief that the American visitor purloined the bones is understandable, and it cannot be eliminated from the realm of possibility since his route went close to the mortuary site. Moreover, Johnson worked for the Smithsonian, an organisation that notoriously — although unbeknownst to Arnhem Landers at that time — had an enormous osteological collection that included the remains of thousands of First Nations people from around the world.

That said, the literal accuracy of the story on this point is far from certain. The acquisition of a human skeleton was well outside Johnson’s remit as a collector of marsupials, which is why he was sent to Australia. There is no evidence that he strayed so far from his area of specialisation, especially at a time when he was already laden with many animal specimens collected on the peninsula. A further and critical factor is that one of Johnson’s colleagues from the Smithsonian, an anthropologist-cum-archaeologist named Frank Maryl Setzler, collected human bones for much of the Arnhem Land Expedition. He would be the prime suspect for the bone theft in the story were it not that he had an alibi. Written evidence shows he never went anywhere near Dilkbany.

While the identity of the robber of Marrarna’s bones remains unresolved (they might have been taken by someone unconnected with the expedition), the Clever Man story again converges with the archival record when it describes the place to which the bones were headed. Setzler dispatched the human remains he stole to the United States, where they arrived in early 1949 as part of a larger consignment ambiguously described as “Natural History Specimens” in the shipping documents.

Something that makes the Clever Man story both clever and cheeky is the way it compresses the expeditionary party into the figure of a single, nameless scientist — as if to remind us of the thousands of Indigenous people who guided, or carried, or collected specimens, or made objects for trade, or shared songs and stories, or, in a myriad of other ways, assisted expeditions down through the centuries, but whose names were not recorded. When the Clever Man story finally gives us the name of a person it is that of Marrarna. Here again, a world of difference between the named and the unnamed is underscored. In contrast to Marrarna’s assertion of power through the declaration of his own name, the skeletons, stolen from grave sites by the Arnhem Land Expedition, were given numerical identifiers when they arrived at their new “home,” the Smithsonian’s United States National Museum. The imposition of those numbers, which were etched into the very surface of the bones, encapsulates their transition from human subjects — known and cared for by kith and kin — into objects in a museum collection.

The need to understand how these mid-twentieth-century bone thefts were tolerated and even valorised has driven my account of an expedition that turned out to be a most quarrelsome affair. Beneath the propagandist blather about good-neighbour policies and scientific mutualism, the project was riven with internal conflicts that were only heightened by a chaotic lack of organisation. Competition between the expedition’s three anthropological collectors, all of whom wanted the best possible “specimens” for the museums they represented, resulted in intra-expeditionary hatreds that would last a lifetime. The gathering of human remains from traditional mortuary sites was enabled by these conditions of conflict, competition and lack of executive authority. Conducted behind the backs of the traditional custodians, the bone thefts showed an extraordinary contempt for the Arnhem Landers who, for the most part, received the visitors with friendliness and good grace.

In order to understand holistically the origins and ramifications of these events, the book reaches far beyond the crowded year of 1948. The timespan covers a little more than a century, beginning with the intellectual formation of Charles Mountford, the originator of the expedition as well as its leader, and ending in the early twenty-first century when some restitution for the bone thefts was finally achieved. In accord with the basic principle, impressed upon me by so many Arnhem Landers, that land, sea, and the relationships among all living entities are our cardinal teacher, I have sought to communicate the social, cultural, and political ecology that created an environment that permitted this expedition to go forth and do what it did.

The great friction at work throughout the history of the 1948 expedition, and so constant through the twentieth century as a whole, is the old and suspicious dance between those who claim to be “modern” and those who the “moderns” classify as “primitive.” The alleged “primitives” are the people who, despite (or indeed because of) that classification, the “moderns” never manage to leave alone. Colouring that relationship between those two peoples is an argument about cleverness: a trait that the Iwaidja storytellers attributed to the visiting American, albeit with a certain irony. When the rejuvenated Marrarna leaps from the bag and loudly proclaims his name and identity, the hapless scientist who thought he had bagged nothing but bones does not look terribly smart. Maintaining “cleverness” in the face of science has long been a strategy for cultural survival on the part of people deemed technologically inferior.

Like other things that are usually hidden, bones are a focus for competing claims about knowledge and thinking. The bones that give structure to our bodies are among the parts of ourselves we don’t directly see. To view a skeleton, we must look at a person who is dead and decayed. Or that was the case until certain forms of technology were invented.

When Arnhem Landers began to go to hospital in Darwin, X-ray machines became the subject of animated discussion. Some people compared them unfavourably with the diagnostic techniques of clever men like Paddy Compass Namadbara, a renowned healer. Namadbara would examine his patients at the end of the day, illuminated by the last rays of the sun. In these conditions he said he could see inside the person and identify the illness. Western doctors were deemed inferior to clever men because they required elaborate equipment to perform this basic task.

To be clever is to see beyond the surface, to know the difference between the shallows and the depths. The concept is famously expressed in the rock art that is especially prolific in the west of Arnhem Land and across the border into Kakadu National Park. There you will find the unique “X-ray” paintings that the 1948 expedition helped make internationally famous in its publications. Such paintings show both the inside and the outside of the person or animal represented. Bones, especially the vertebrae, and sometimes the internal organs are clearly painted. The scientists on the expedition spent a lot of time looking at these paintings. They photographed them and copied them into their notebooks and they collected many examples, painted on bark by local artists. But for all the clever things they did in acquiring and exploiting this knowledge, it seems that the deeper truths inherent in the paintings eluded them.

Who were the clever ones?

That is the question that haunts the record of this expedition. •

This is an extract from Martin Thomas’s Clever Men: How Worlds Collided on the Scientific Expedition to Arnhem Land of 1948, published today by Allen & Unwin.