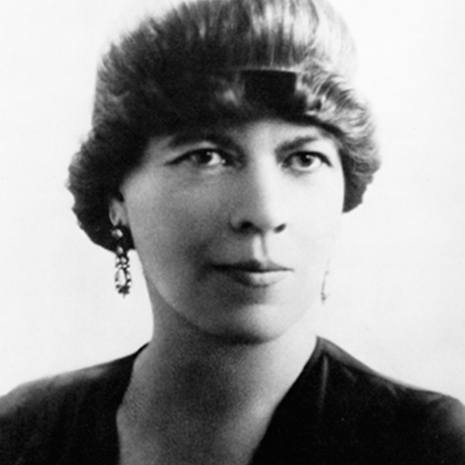

WHEN a mobile library fetches up outside Buckingham Palace in Alan Bennett’s The Uncommon Reader, the Queen decides to investigate. Seeing a novel by Ivy Compton-Burnett on the shelves, she takes it down reflectively, recalls that “I made her a dame,” and decides to borrow it. Well, she just can’t get on with Ivy, finds her too demanding, but encouraged by a member of her staff she does become addicted to reading. Some months later, when she is back in the mobile library, she decides to give Ivy another go, and this time finds the dame with the pie-crust hairdo “unsentimental, severe and wise.”

Those three adjectives constitute an admirable accolade for the wittiest and most unsparing of twentieth-century English novelists. Just look at the following, surely one of the most perfectly phrased sentences of the modern novel: “Miss Burtenshaw had retired from missionary work owing to the discomfort of the life, a reason she did not disclose, though it was more than adequate; and was accustomed to say she found plenty of furrows to plough in the home field…” (A House and Its Head). If the Queen had come to appreciate prose like that, she had indeed become an uncommon reader – unlike all those more common but less perceptive readers who say dull things like, “Compton-Burnett’s characters all sound the same” or “You can’t tell who’s talking,” unaware of the acid test they are failing.

Compton-Burnett’s first novel, Dolores, appeared in 1911, when she was twenty-seven, but though it apparently sold quite well she suppressed all reference to it and didn’t publish another until 1925. And for good reason. Dolores is a stodgy pastiche of George Eliot and Henry James, with no sign of the fierce individuality that would characterise the great series of nineteen novels that would follow. These appeared at roughly two-yearly intervals until she died. Her final one, aptly titled The Last and the First, appeared posthumously in 1971; like the rest, it was published in hardback, with an austere yellow jacket, by Victor Gollancz. She had a coterie of admirers, including Graham Greene, but it must be said that the books are not for those who, misled by their titles, are looking for comforting tales of family life in country houses.

As for those titles, the most commonly recurring word is “and,” suggesting from the outset that they will be concerned with some sort of connectedness, some kind of relationship. Here are a few samples: Pastors and Masters (1925, the breakthrough novel, set in a school), Brothers and Sisters (1929), Men and Wives (1931), Parents and Children (1941), Elders and Betters (1944), Manservant and Maidservant (1947). And so on, right up to the end. Further, so many of those titles suggest that it is, above all, the dynamics of family life that fascinate – and often appal – her. Rather than deal in generalities about her work, I want to focus on one of her wittiest and most uncompromising novels, A Family and a Fortune, with some reference to A House and Its Head. If these titles suggest a literary Downton Abbey, well, you have been warned.

A family circle

In the Gaveston household, in 1901, the family is gradually assembling for breakfast. Neither parent, Blanche nor Edgar, is a severe authority figure; it is daughter Justine, at thirty the eldest child, who does her best to run the family’s affairs. Elder son Mark will inherit the place; next son Clement is setting up in a teaching post in Cambridge; and “little boy,” fifteen-year-old Aubrey, observes them all with a perspicacity beyond his years. Also living in the house is Dudley, Edgar’s selfless brother and the object of his strongest feeling, as well as a butler Jellamy, of almost Jeeves-like articulation, and various underlings. As the breakfast scene proceeds, the diagnosis of the family and its degrees of affection become clear.

A disruption in the family circle, signalled in the opening chapter and eventuating in the next, is provided by the arrival to stay at the “Lodge” attached to the Gavestons’ house (having a lodge is our key to its substance) of Blanche’s very old father and her formidable sister Matilda Seaton, who makes the most of a disabled leg and a gift for self-serving innuendo that will give Justine a run for her money. They are accompanied by Matty’s patient companion, Miss Griffin, and are exhorted by Matty to “be as grateful as they will expect us to be” in the same tone of enjoyable bitchery as she will later say of “dear Justine,” “so sure of her right to improve us all and so satisfied with it.” The encounters between these two women who use the language of conversation as weaponry provide some of the book’s choicest moments. “‘I have had my say and I always find that enough,’ said Justine, who was wise in this attitude, as she would seldom have been advised to go further.”

The next entrant on the scene is Matty’s old friend Maria Sloane, who, in this company, passes for a plain-spoken woman. Even so, she is given the wisdom to say, when she has married the recently widowed Edgar, “No one tries to take anyone’s place… Empty places remain and new people make their own.” She is allowed one of Compton-Burnett’s great lines: “I like good people… I never think people realise how well they compare with the others.” Her own role in the ensuing events will provide some evidence for this idea. Her appearance, quickly followed by the news that the self-effacing brother/uncle, Dudley, has been left a fortune, will cause major ripples in the Gaveston household. The responses to these narrative tighteners, and more, reflect elements of disgruntlement and even viciousness. As Dudley himself said earlier, “Well, of course, people are only human… But it really does not seem much for them to be.”

There will be other threats to the superficial order of the Gaveston household, particularly when, shortly after his wife’s death, Edgar displaces Dudley as Maria’s fiancé and with surprising speed makes her his wife. And other things happen off-stage, including Matty’s cruel dismissal of Miss Griffin, Dudley’s attempt to rescue her and so on. These events, brilliantly calculated to alter our perspectives on the characters and only obliquely dramatised, are in the end no more than the necessary skeleton of the novel. The flesh is what matters, and this is essentially located in what people make of the events in conversation and what their responses reveal of them. It is in the relentless dialogues, often around meal tables, that the truth gets teased out, with some acceptance of Maria’s simple dictum, “We all do some odd things in private.” There is an austere affirmation of the institution of the family. Not of course anything along feel-good lines, but a recognition of what might be contained by it.

“There is probably nothing like living together for blinding people to each other”

Think how much of the history of the novel, the Anglophone novel at any rate, is concerned with what makes families tick – and kick, against each other, that is. There is often a patriarchal figure, such as Duncan Edgeworth in A House and Its Head, whose expectation of unquestioned authority almost demands subversion. And yet Duncan will marry three times, taking as wives two of the most admirable, and one of the most intelligent, women in the book. In the confines of the Edgeworth family, misdirected lust and even murder may shake the foundations of the household, may require a “blinding” of the inmates to the behaviour of one of their number, but the structure of the novel again and again proves equal to these assaults. This has nothing to do with sentimentality. Compton-Burnett would scorn this as ruthlessly as she strips cliché of all credibility. Anyone who utters a cliché, as Justine does when she speaks of the effect of absence on fondness, cannot expect to be taken seriously – or, worse, she will be taken as seriously deficient, intellectually and even morally.

Compton-Burnett’s households are all Edwardian. She claimed to have “no organic knowledge of life after 1914,” but the focus on a particular period, setting (large house in village) and class (upper-middle) doesn’t limit the resonance of the novels. These families characteristically comprise a parental couple, one of whom may not last the distance, several adult, unmarried siblings, the odd child who speaks with disconcerting perception, and a battery of servants. There are neighbours who drop by with variously welcome whiffs of the world outside, but their function is less to propel events than to provide another forum for their discussion, because in a Compton-Burnett novel that is where the real action takes place.

For instance, the Middletons in A Family and a Fortune have one primary function and that is to provide an audience for the airing of family affairs, and sometimes to provide an outsider’s responses. They are not necessarily immune from the lethal shafts of Compton-Burnett’s wit, as in: “‘We need not thank you,’ said Thomas [Middleton], uttering the words with a sincere note and acting upon them.” And don’t imagine “sincere” in this context is an unequivocal compliment. Some neighbours make their presences felt more forcibly than the woolly Middletons. For example, the foolish Beatrice in A House and Its Head rushes round the village to pass on “the message of Christmas” to the Edgeworths and other reluctant recipients.

The houses in which these families live are virtually never described but somehow emerge as palpable presences in the novels. It is as though the author refuses to be unnecessarily diverted from her prime purpose of showing how people reveal themselves through what they say. Major events do occur – people elope, a companion is turfed out of the house, people die – but we are not present when they happen. We are present, though, when the characters gather to make what they will of these events.

“That goes without saying”

This is the running joke in her novels, though the word “joke” makes it sound too contrived. The point is that nothing goes without saying in her novels. In A Family and a Fortune there are at least eight occasions on which someone, usually not the most acute person present, says this. The novels are all but entirely made up of dialogue. There is almost something grudging about the time she needs for those spare descriptive sentences in which a newcomer to the scene is introduced (with even less to spare for the physical settings) – and we had better remember what we were told then because she is not going to pander to our inattention by repeating it. Furthermore, she merely uses “said,” if that, to indicate a speaker. She has no use for adverbs telling us how the words were “said,” much less for variants such as “exclaimed” or “muttered” or “cried” that lesser writers might employ to give colour to their work.

What matters is what is said, that is, the content of the comments and the diction that embodies them. It is this that identifies the speaker. Someone as tersely cynical as Clement Gaveston in A Family could not possibly give tongue to the fulsome locutions of his sister Justine. In the world of Compton-Burnett, the most voluble speakers need to be watched carefully. Their flow of words is apt to be nourished by crassness, self-regard and hypocrisies of many entertaining hues. Justine can’t open her mouth – actually it is easy for her to do this – without seeming to indulge in public self-laceration but in reality drawing attention to her own excellences as she sees them. She berates her brothers as “indifferent conversationalists” (in a character we trusted, this would rank as a serious Compton-Burnett criticism). Clement’s reply, “If you wish us to be anything else, you must allow us some practice,” shows us what to make of Justine’s outpourings.

In another instance, the appalling Dulcia Bode in A House and Its Head is forever exhorting people to meet challenges they haven’t noticed, rallying the spirits of those who would rather be left to their own devices and, in the guise of being the bringer of glad tidings to the houses she visits, being deeply malicious as well as utterly crass. Compton-Burnett identifies her inadequacies by giving her a flow of clichés: she has only to open her mouth to put her foot in it and to condemn herself as a fool, and she is immensely diverting to the reader as she goes about it.

“I like good people…”

Though Compton-Burnett attributes the line about “good people” to Maria, it is easy to imagine her embracing it. Although it is almost an acknowledgement that “goodness” may not be as intrinsically interesting (to readers, for instance), the rest of Maria’s aperçu does suggest that those “others” could do with a little self-appraisal, and that they might find themselves wanting in the process. The world of the novels has its share of “good people” and it is one of her achievements to make them genuinely impressive, even though “the others” more often get the best lines.

In A Family and a Fortune it is Dudley who most clearly qualifies as one of their number. He is aware of what he owes to his brother’s family and, when he unexpectedly inherits the eponymous fortune, his first thoughts are for what he might do for the house and its inhabitants. When Edgar supplants him as Maria’s future husband, Dudley knows “he must get through the minute… that he must meet his brother’s children and break the truth, before he went away alone to face the years.” There is a clear-eyed quality about his stoicism that is devoid of sentimentality, and there is a further goodness in his offer of marriage to Miss Griffin when Matty turns her out: it is “simply an impulsive offer of rescue.”

In the end, the bond between Edgar and Dudley proves strong enough for Dudley to return to live in the house with Maria in place as Edgar’s wife. He has been ill but insists that he needs to go downstairs again, saying, “I can’t be shut away from family life; it offers too much. To think that I have lived it for so long without ever suspecting its nature.” Dudley is a good man and he means this, even if Compton-Burnett herself once said that she felt more harm was done in the name of the family than of any other institution. It is not that she doesn’t recognise and appreciate real goodness when she sees it, but she is also, and always, darkly aware of the threats to it. Indeed, she must surely have had this in mind when she said…

“I am appalled by the threat and danger of life”

This remark is made by Mark Gaveston, heir to the house, and not one notably given to observations of great prescience. Those are more usually the lot of his younger and more cynical brother, but this time it is Mark who seems to echo the author’s own view. Compton-Burnett’s novels never venture into the larger world outside the family and its dwelling places, but within that narrow physical setting she manages to imply wider possibilities. The family becomes a sort of microcosm for the potential for larger disorder.

I don’t mean that there is any conscious intent on her part to make the internecine struggles of family life a metaphor for, say, the first world war; only that, in writing about what she knows, she exhibits an amazingly acute sense of the ways in which malevolence and treachery of various kinds can be translated into the most damaging action. In A Family and a Fortune, Matty Seaton’s monstrous ego and self-pity (disguised, she fancies, as courageous restraint) takes the form of bullying that cruelly threatens the serenity of other lives. She requires herself to be the centre of attention on all occasions, diverting conversational attention (even more rigorously than Justine) to her own self-perceived virtues. And in A House and Its Head, the treacheries that derive from lust and self-absorption give rise to alarming repercussions.

And yet, “appalled” as Compton-Burnett may be, there is nevertheless an austere moral code and compassion at work in the novels. She has no truck with easy judgements; when Maria, engaged to Dudley, accepts Edgar’s offer of marriage, it is recorded as something that has happened. When an adulterous couple is seen (and often major “events” are “seen” from, say, a window, rather than up close or after a serious lead-in) to be hurrying away from the house that will feel the effects of their behaviour in A House and Its Head, she allows a character we respect to say, “I think it is best to let someone in a great difficulty get out of it in any way she has thought of.” In the same novel, a children’s nurse is involved in what amounts to crime, and is allowed to justify herself on the grounds that “my man was ill” and she needed money. This is not a conventional morality at work, but an understanding of human motivation and its propensity for creating “threat and danger” in life. Even so, she is always aware that the wrong “is never the only thing a wrong-doer has done.”

So…

I haven’t left much space for discussion of the wit and precision of her prose. She is undoubtedly a great stylist but the style never seems affected; instead, it feels like the only way someone who sees the world as she does could write. The wit is there in the way people reveal themselves in what they say: “Aunt Matty would have been burnt as a witch at one time,” says Clement at one point. “Does Clement’s voice betray a yearning for the good old days?” says Aubrey.

The fools and the hypocrites, the egoists and the gushers, have no idea how they expose themselves, but the intelligent and the good are on to them, and much of the underlying wit is in the precision with which these latter characters latch on to the falsities of the others. At one point, Justine utters the recurring line, “That goes without saying” to be met with the reply that takes her up syntactically as well as with intent to deflate: “Then why not let it do so?”

Ivy Compton-Burnett’s novels have been variously compared to Greek tragedy, Henry James with a dash of Oscar Wilde, and many others. This suggests a sort of critical fumbling rather than serious indebtedness or affinity. The fact is that there is simply no one like her, demanding and rewarding in equal measure. I once read an assessment of her work that claimed she was too idiosyncratic to be considered major but too important to be dismissed as minor. I can’t remember who said this but in my view it was spot-on. •