We have a strange relationship with the past. Obsessed with collecting, documenting and archiving, it seems we are less able to deal with loss and transience in our own lives. Reminders of the past – monuments, statues, plaques and street names – are enmeshed in the places we inhabit, but the pastness they relate to doesn’t appear to have much in common with our own lives in the here and now.

The past, it seems, is something that belongs to the museum, to the archive and increasingly to the digital world of Google, which stores our every virtual move with the same precision as it stores major historical events. French historian Pierre Nora famously argued that modernity’s over-preoccupation with history has broken our relationship with the past, moving us from a solid and steady past to a fractured one. “Given to us as radically other,” he writes, “the past has become a world apart.” In a world that continuously strives forward, the confrontation with absences – with people, things and places that are not here – leaves us speechless, frightened, baffled.

It is of such inexpressible moments of memory and forgetting that Katrin Koenning’s photographs speak. Through her diverse body of work, the German-Australian artist uses a powerful visual language to lay open the paradoxical interplay of past and present in everyday life. Through images of Australian landscapes, or fleeting moments in Melbourne’s laneways, or the stories that continue to shape her own family history, her photographs touch on some of the most deep-seated silences that seep into our engagements with people and places. In finding ways to speak of the stories that remain untold, Koenning’s images have something profound to say about life and living in contemporary Australia. In their quiet persistence, they also manage to raise broader questions about photography, memory and the human condition.

View Over the Pacific Facing West from Amity Point.

Interestingly, the very moment that initiated Koenning’s passion for photography could be described as an act of memory-making. Born in the post-industrial town of Bochum in the German Ruhrgebiet, she grew up dreaming of becoming “a painter, a singer or an astronaut.” But a tragic event changed everything. A few weeks after she finished high school, Koenning’s best friend died in a plane crash over Iceland. He had been a keen photographer, and she inherited his camera and all his lenses. “I took that camera and left for Iceland,” Koenning tells me. “I needed to find a place to get my head around it, I just needed to be where he died.”

Being near the place where her friend had died and taking photos there made her feel near him. Close to the entanglement of memory, place and photography that still features in Koenning’s work many years later, this act of memory-making had nothing to do with the often-criticised tendency of photography to freeze a moment in time. Instead, she used the camera to question time’s inescapable power. Taking photographs allowed her to follow the traces of what had been lost and make the past an active part of the present.

Upon returning from Iceland, though, the young photographer was confronted with the elusiveness of images and memory. “When I took out the film in Germany, all the images I had taken came out pitch black,” Koenning laughs. “There was nothing on it, not a single picture.”

About a decade later, having migrated to Australia and having had her photographs exhibited in major international festivals from New York to Delhi, Katrin Koenning’s images don’t come out pitch black anymore. But she continues to use the camera as a means of understanding the world she finds herself in. Dealing with such large themes as memory, movement and loss, she doesn’t shy away from looking deep into her own life. True to the documentary tradition in photography, which her work links into, Koenning approaches her subjects from an experiential point of view. She forms her understanding through the small gestures, stories, objects and sensations that form our everyday engagements with the world around us. As quiet, intimate and unexciting as these layers of experience may appear to be, in her photographs they receive a poetic authority to speak on their own terms.

This engagement with memory as a lived experience becomes particularly apparent in a recent body of work entitled Dear Chris, which was shown at the Edmund Pearce Gallery in Melbourne and the Queensland Centre for Photography. In this multi-layered photographic installation Koenning confronts the tremendously difficult and notoriously concealed topic of suicide, death and mourning by giving insight into a painful chapter of her own family history. The entire body of work is a tribute to Chris, the husband of Koenning’s cousin Alana, who in 2010, at only twenty-nine years old, ended his own life.

Throughout his life, Chris had battled with depression, a “front row battle,” as Koenning puts it, which was marked by constant struggles with medication, conflicting doctors’ opinions and, in the end, a growing silence. Yet his life was constituted of much more than this pain. “Chris loved many things, I wonder if silence was one of them,” Koenning writes in the introductory notes to the exhibition. “He loved Alana, nature, his dogs, the Simpsons. His Hilux, Nirvana, cigarettes. Dreamt of being a pilot, of doing other things.” For the people left behind, these aspects of Chris’s life retain a strong presence. Made material through objects, photographs, the daily paths he used to walk and even the landscapes he inhabited, the everyday memories of Chris that continue to accompany the photographer’s family speak of everything but an absolute absence.

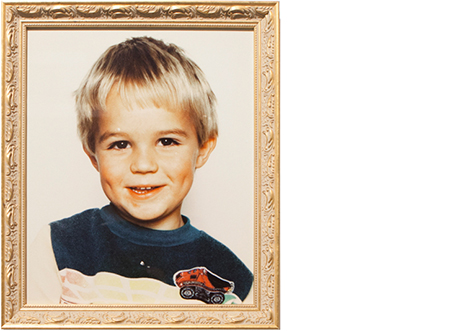

Consequently, Dear Chris depicts the many traces the past leaves behind – traces that have the power, the photographs suggest, to form and transform the present. Composed of three interchangeable chapters, the installation shows vernacular pictures from Chris’s childhood photo album, photographs of some of Chris’s objects kept by Alana, and photographs of places of significance to Chris. In showing these intimate layers of memory and forgetting, of hope and loss, and exhibiting them in their lived messiness, Koenning has succeeded in removing suicide from its dark narrative conventions and making us think of it in new ways.

From the Album # 1.

Dear Chris was driven by a deep sense of urgency to tell stories that would otherwise remain unheard. Almost immediately after the artist heard about Chris’s death, the idea of creating a body of photographs began forming. “As a society we don’t talk about death, let alone about suicide, so I felt a sense of responsibility,” Koenning explains. “But I was also aware of the fact that out of the family I was probably going to be the only one who could do that, because as an artist I had the right tool kit.”

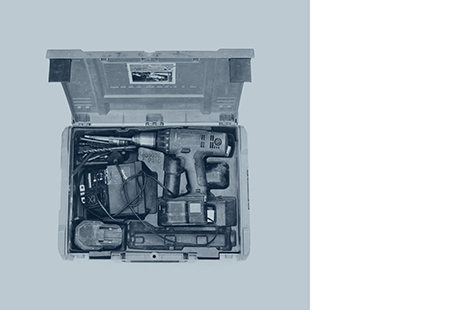

About a year later, she approached Chris’s wife Alana, who immediately supported the project and supplied the photographer with the objects that came to form a crucial chapter in the project. Alana’s openness to sharing some of the objects she kept after Chris’s death lends the work an intimate immediacy. Depicted against colourful backgrounds, seemingly mundane things such as a pair of trousers, a wallet, a tool kit or a tie take on a life of their own. In Chris’s absence the objects have lost their original function, hovering somewhere between life and death.

In The Invention of Solitude Paul Auster writes about the ghostly life objects take on after the people who possessed them die. “They are there and yet not there,” he writes, “tangible ghosts, condemned to survive in a world they no longer belong to.” It is this spectral dimension of the past – the paradoxical ways in which people, things or stories that ought to be absent leak into the present and, if only for a split second, come to touch us – that Koenning’s photographs depict.

Toolbox #1.

The Veil.

Koenning’s work isn’t just remarkable for its visual poetry and its courage to speak of things that are almost beyond speech. True to the young photographer’s love for photography as an art form, her work also pushes boundaries and questions established visual conventions. In Dear Chris the artist quite consciously breaks with the taboo of intermingling text and image. Art theorists and photographers still disagree over the extent to which words and images are two separate means of representing the same end, or whether, in fact, the narrative subverts the visual and vice versa.

In most contemporary photography galleries, descriptions, captions and artists’ statements are kept separate and sparse. In Dear Chris, Katrin Koenning consciously ignores this dichotomy between words and images, and puts the interplay of showing and telling to her own use. As well as the beautifully crafted background story that introduces the exhibition, the poetic captions accompanying some of the images add new layers to the photographs.

A photograph showing a clearing in an Australian forest, for example, is entitled “Beerburrum State Forest (you used to ride your bike through here).” Another photograph, depicting clouds in the sky, carries the caption “The sky above place of death.” These words, as sparse as they are, give an image of a forlorn forest or of an open sky a radically different appearance. They link the audience into a story and transform seemingly innocent places into sites of meaning. The forest is not any forest. It is the forest Chris used to love and ride his bike through. Likewise, the sky is not any sky. It is the sky above the place where Chris took his own life.

Beerburrum State Forest (You Used to Ride Your Bike Through Here).

Rather than weakening the photographs’ visual strength, Koenning’s use of words opens the doors to layers of imagining and seeing that would otherwise be inaccessible. Seeing, her work shows, is never absolute. Instead, her photographs hint at a way of experiencing the world that goes beyond the mere visual and yet challenges the predominance of words as the ultimate tool for meaning-making.

Or a Pilot.

As well as intermingling words and images, Katrin Koenning has developed a distinct visual language that is built on a deep understanding of light. Because she literally and metaphorically draws her subjects in and out of the light, many of her photographs bear a close resemblance to paintings.

This comparison isn’t as far-fetched as it might first appear to be if one considers the roots of the word photography, which derives from the Greek photos, which means “light” and graphos, which means “drawing.” Photography, then, literally means “drawing with light,” a description befitting Koenning’s photographic practice. In the spectacular series Thirteen: Twenty Lacuna this play with light and dark, memory and forgetting, movement and stillness best comes to the fore. During one of her daily walks around Melbourne to take photographs, Katrin discovered that in a specific laneway in the CBD at a specific time of the day, and only for twenty minutes, the light is so powerful that it illuminates everything it touches. The photographs that result from her engagement with this very place and light show people rushing in and out of their offices, in and out of the laneway, in and out of the light. Illuminated by the stream of light falling into the street, they appear as if on a stage; as if they weren’t office people caught up in the humdrum of life in the city, but tragic figures in a play. Using the backdrop of the symbolically important shadow as a means to portray the interplay between past and present, the images could also be read as depicting a stage on which questions of memory, history and forgetting are played out.

The Marchers.

The real importance of Koenning’s work lies in her ability to depict complex questions concerning the human condition with a lightness and quietness that is captivating. This sets her apart from many of her contemporaries, who are still caught up in dominant postmodern visual conventions that are led by an urge to shock their viewers into a political consciousness. Whether it’s through her images of movement and transition, or through her ongoing engagement with the Australian landscape, Koenning doesn’t attempt to capture with an aggressive loudness, but with silence. This fills her images with a tenderness that is heartbreaking. Under Koenning’s eyes the Australian landscape, often depicted as tough, impenetrable and unforgiving, turns into something fragile and shy. And the beach, often portrayed as the stereotypical space where Australianness is acted out, turns into a stage for intimate encounters.

The silence that runs through all these images doesn’t hint at an emptiness, or stand for a lack of interest in political questions. As the Australian historian Greg Dening so poignantly puts it, silence is never empty, but always a relationship: “Silence always has a presence in something else.” It is of such a silence, a silence that is full of potential meanings, that Koenning’s photographs speak.

Elwood Scene #1.

A body of work Koenning is currently working on carries the title, A Country Big Enough to Disappear In. In this project she depicts her relationship to the Australian landscape, a relationship that is still growing. Despite having lived in Australia for eleven years and studied here, and with many family members having migrated here, she wouldn’t call Australia her home. While many people laugh about the ugliness and grittiness of Bochum, the town where Koenning grew up, and congratulate her on her decision to migrate to Australia, to her it is still home. Home, the photographer says, is almost like language: “You don’t even really think about it because it’s such a part of you and always will be.” While she is still learning the grammars of being Australian, this absence shouldn’t be misunderstood as a shortcoming. The experience of being new to a place has also opened the door to look at herself and the world in new (displaced) ways.

Fowlers Bay Camp #1, from the series A Country Big Enough to Disappear In.

In the end, this experience of transition, of feeling somewhat in-between, has enabled Koenning to depict life, both in Australia and beyond, from a unique perspective. Like a second pair of eyes, the camera allows her to look into the surrounding world, being both part of the moment depicted and removed from it. It allows her to zoom in on, highlight, exaggerate or dissolve fragments of what appears in front of her. The great Hungarian photographer André Kertész once said, “The camera is my tool. Through it I give reason to everything around me.” In similar ways, Koenning’s photographs bestow meaning on the world they depict; together they form a landscape of intimate moments, details, places and stories – a world that is small enough to feel grounded, and yet big enough to disappear in. •