I am an Australian perforce and by chance. When my father became naturalised in 1939, I was twelve years old and automatically included in the process, but I could as easily have become an American or a Russian. For most of my childhood I was not an Australian, despite the fact that I lived here. I think I began to be an Australian at the end of the second world war, although even now I wouldn’t call myself “dinkum.”

As a child, the most un-Australian thing about me was my name. When my mother and I arrived at Port Melbourne in February 1929 I was called Amirah Gutstadt. The mother with whom I had travelled the long weeks from Toulon was called Manka Gutstadt, but the father who waited for us at Station Pier after a year on his own in Melbourne, though described in his passport as Itzhak Gutstadt, was already known to a small group there as Isaac Gust.

Being called Amirah Gust in those days was to prove a burden. Today, many Australian Smiths or Browns will twist their tongues around Witkowski or Komarowski without too much fuss, and Jesaulenko, transformed into Jezza, is an oft-mentioned football hero. In 1929, though, these people were all still unborn in Poland or the Ukraine, and Melbourne schools were filled with less exotic names. My father’s first Australian landladies were Fitzgerald and Jones; the people who lived downstairs in the first house I can remember were called Green.

My father’s family had become Gutstadt – so my father used to tell me – during the old times when the Jews of Poland, who were all then called son-of-this or son-of-that, had to take German surnames for administrative convenience. If they were lucky or had money – which I supposed amounted to the same thing – they became literally “Eagles” or “New Cities” or “Buttonmakers” or “Good Towns.” If they were unlucky and poor, or if the official had it in for them or had a sense of humour, my father used to say, they became “Big Heads” or “Fat Bellies.” So while my father’s ancestors in Poland became Gutstadt (which means “good town”) by decree, he became Gust in Australia by an altogether less formal means.

At the house where he boarded with several other recent arrivals, a laundryman called every Saturday afternoon to collect and deliver the washing.

“What’s the name?” he asked the landlady.

“Gutstadt.”

“Eh?”

“Gutstadt.”

“Cripes, how d’yer spell that?”

“G-U-T-S-T…”

“Aw, that’ll do, can’t write the rest. But I can’t call him GUTS! What say I change it to GUST?”

“Because you blew in like a gust of wind!” explained the landlady, a charming and intelligent young woman from Lodz, and the first of thousands who would make that joke.

So Gust it was on the laundry, and Gust it became to the Australian government and trade union officials to whom my father had to give his name before he could get a job. And although all the Russian and Palestinian Jewish migrants who had come from the same towns as my mother and father knew us as Gutstadt, when I was taken by my mother and enrolled in the “bubs” at Princes Hill State School in 1931, I became Amirah Gust.

Gust was bad enough. Amirah was worse. It was odd, even for a Polish Jewish girl. It was neither biblical, like Sarah or Miriam or Esther, nor yet a well-known Hebrew word for something beautiful, like Zipporah (Spring) or Hephzibah (My heart’s desire is in thee). It was Hebrew and it meant, my parents used to tell me, “the crown of a tree”; it had been suggested by one of my father’s pioneering friends in Palestine because it was both beautiful and unusual. It was the first bane of my life.

“What’s your name?”

“Amirah Gust.”

“What?”

(And I would repeat it.)

“Surname?”

“Gust.”

“Christian name?”

“Amirah.”(Christian indeed!)

“How do you spell it?”

The Gust was easy enough both to say and spell, thank God, though no one had ever heard of it, which was not surprising since it had been hacked by bush surgery out of a “real” name.

“What an unusual name!”

(I managed a sickly smile. What would they have said, and what would I have done, had it still been Gutstadt?)

But that awful “Christian” name. Polish Jews always had two versions of their names, a Jewish version and a Polish version – for times like this, I supposed. My mother was both Miriam and Manka; my father Isaac and Itzhak; my Adler uncles, Bernard and Berek, Chaim and Henryk. Only David was a name acceptable in all cultures, and so my oldest uncle was always David – in Poland, in Palestine and, much later, in Switzerland.

It was bad enough, I thought when I grew older, to have to give Amirah as a “Christian” name, but in those days the problem was always having to spell it out because no one ever got it right. Even when people finally mastered the spelling, they could never pronounce it; and the very worst offenders were the schoolteachers. One year their accent was on the a; another on the i. It is hard to explain the number of people, then and now, who were and are sure the name must have an l in it. One year I was Almyra, another Almeara, another… But enough!

Not only was my name un-Australian in its combination of letters and sounds, but it was also un-Australian in another important way: I had only one first name.

“Surname?”

“Gust. G-U-S-T.”

(I soon learned to say and spell out my name, automatically.)

“Christian names?”

“A-M-,” et cetera.

“What’s your second name?”

“I haven’t got one.”

“You must have.”

“I haven’t.”

Everyone else in the class, in all of Princes Hill State School, in the whole world as far as they knew, had a second name, except me. And how I longed for one. It wasn’t the custom for Jews to have a second name but it was the custom for Australians. When I got to the age when I covered pages torn from exercise books with a mixture of ladies with page-boy hairdos and very straight noses and various trial signatures, I always tried out a variety of middle names: Amirah Anne, Amirah Margaret…

My father had done something about part of his name and many of our friends too had changed their names in a half-hearted attempt to turn them into something simpler and more Anglo-Saxon, with changes that only partly disguised our foreignness. The suffixes “-kevicz,” “-ovicz” or “-ski” were sliced off, but none of us became Smith or Brown or Jones.

Throughout my early childhood, when I was not yet conscious of my looks, my name seemed to me the most persistently un-Australian characteristic I had. And I could do nothing about it.

I could, and did, persuade my mother to cut the hood off the red rain cape she had brought from Europe for me. No one else had one and, besides, I was called “Red Riding Hood” whenever I wore it. I could try to get her to make my lunch sandwiches with thin slices of white bread filled with dainty morsels of Kraft cheese and Marmite, instead of burdening me with thick hunks of rye bread on either side of generous slabs of sausage; but that was more difficult, as it might offend her.

So there I was, with this weird “Christian” name and surname and with no second name. A freak. Not only that, but I had no cousins, no aunties and no grandmothers. Other girls had cousins, sometimes many of both sexes, with aunties and uncles to match, and they had grandmas, many of whom seemed to live in the country, where they liked to go and stay. We had no relations in Australia.

The rooms to which my father had moved before we arrived were at 27 Park Street. Around the comer from his lodgings in Gatehouse Street, they were the upper floor of a terrace house converted into two apartments. My mother found herself not in the leafy green garden suburb she had imagined from “Park Street, Parkville” but in a sliver of terraces built almost on top of wide, hot streets bounded on the east by the broad and empty thoroughfare of Royal Parade, on the south by the equally wide but uglier and more characterless Flemington Road, on the west by the dry wastelands of Royal Park, and running out into Brunswick on the north. It was a bitter disappointment.

She had met some Australians on the ship and imagined some terrible disease to be raging out there, as so many young people had lost their teeth (a fact she discovered in the bathroom, to which they brought false sets in glasses of water). All in all, my mother’s first impressions were bound to be less favourable than my father’s as she was less inclined immediately to welcome every step as though it were the best possible one to take, less inclined to praise every new place or find instant fault with the old. Itzhak could never admit any fault in any road he had chosen, nor any good in what he had rejected. Not only had he never, as far as I knew, cried over spilt milk, but he also never admitted that it had been spilt. My mother was more judicious.

When our first landlords, the Fitzgeralds, moved out of Parkville to a house with a garden further away from the city and the new owners of the terrace proved unfriendly to their immigrant tenants, we moved too. But we did not go far – only a couple of miles north, past the boundaries of Parkville, to West Brunswick. We moved to another terrace built in 1890, to another upstairs flat and to another Park Street. All the streets I lived in were called Park Street. Opposite our place stood vacant land again. This time the land housed a disused cowshed in which, later, a pinched, bony, pale and ferret-faced school fellow called Noel undid his braces, let down his long short trousers over his thin, bony legs to his thick boots and showed me what little boys were made of.

Our terrace house was the last in the row. Next door was the railway line, which I never crossed, for I liked boundaries. My paths led me in other directions: left down Park Street to Royal Parade, which narrowed into Sydney Road at the Sarah Sands Hotel; quickly past the open door and the blast of cool air spoiled by the unpleasant smell of beer and the harsh, raised voices of drinkers (sometimes frightening drunks would lurch out and I would move even faster); along Sydney Road a bit and into the familiar lolly shop and the ham and beef shop, both near the corner, and as far as I ventured alone. Friday night was late shopping night when, my hand held firmly in my mother’s, I penetrated further along Sydney Road and into the bigger, crowded shops filled with noise and lights, or stood and listened to the Salvation Army beating tambourines and singing songs on the corner.

In Belgium my mother had been warned never to have any more children. The complications of my birth, which had put her back in hospital six weeks later, and a kidney operation in 1928 would, it was said, make further pregnancies dangerous. The warnings were mistaken, as it turned out, but no one knew it at the time; so I was the treasured only child of immigrants in a very strange land. We three did very many things together and spent many hours with my mother and her friends. From the time I left the high chair my father had provided, we always ate together, and when friends joined us for a meal I sat quietly and listened to the talk.

When my parents began to go out at night, I was left at home alone, provided that someone was in downstairs. My mother always tucked me into my eiderdown before she left and though I was frightened of the dark from a very early age, I remember only rarely being alone and frozen with fear. The terrors of the night, which were nameless but vivid and lurked in the darkened rooms of our flat or more horribly outside in the streets, were kept at bay when I was hidden deep inside my eiderdown cocoon. I was often frightened in the daytime too. I was warned most seriously by my mother against taking sweets from strangers who would “take me away.” What for? I never asked, because I knew that it was something so awful that it could not be talked about.

For the first eight years of my life in Australia, my world was the small area on the northwest fringe of the city bounded by Sydney Road, Princes Park, Lygon Street, Carlton and Park Street. And for the first four or five years there, all the people who inhabited my world (apart from landladies) were Jews like us, and mainly Polish Jews. The languages I heard were Polish and Yiddish. My first close friends were Zipporah, Marsie and Lily, all three daughters of recent Polish Jewish immigrants. All the friends I remember were Jews, and most were Poles. It was an important distinction. To my family and their friends, “Poles” or “real Poles” always meant Catholics. The others were Jews. But in fact, my mother and many of her friends considered themselves Polish and spoke Polish rather than Yiddish among themselves. Many spoke Yiddish as well, however, like Itzhak.

We knew no one who lived across the Yarra in the southeastern suburbs, though we knew that some Jews did live there, for they had built the large synagogue on St Kilda Road for their worship. We had no connection with any synagogue; the Kadimah, the Jewish cultural organisation founded in 1913, was our centre for plays, concerts and children’s festivities. Here we made new friends of earlier migrants determined to keep the old Yiddish culture alive in the new land; and I met my friend Miriam.

On Sundays we all walked to each other’s places, and my father would comment on the lack of activity in the streets.

“You could sleep in the street without being disturbed!” he marvelled. “In Catholic Belgium, Sunday is a day of amusement. Bars and picture theatres are open, people enjoy themselves. Here in a Protestant country, Sunday looks like the Jewish Sabbath! Absolutely nothing to do. Nowhere to go. Nowhere to get a cup of coffee.”

“No coffee any day! Only coffee essence!” exploded my mother, late of Warsaw, Brussels, and briefly of Tel Aviv.

The Melbourne Sunday didn’t bother me, though, for there were the black horse-drawn cabs clopping along for my pleasure, the zoo was so close that I could hear the lions roaring from my bedroom, and I loved the walk with my mother and father down the emptiness of Royal Parade through the leafy Tin Alley shortcut in the university and across into Lygon Street. All this was plenty for me.

My mother had picked up some English from the landladies and from the shopkeepers (at first, she used to say, she thought Kiwi Polish was a strange fellow countryman) but she spoke mainly Polish in those years. The language of our home was Polish. My earliest words, though, had been French. I began to speak in Brussels and, on the ship coming to Australia, had amazed the kindly English-speaking men and women. “That such a little thing should speak French!” they had marvelled. The childish words which my mother and I used for parts of the body were French and I used to “make pipi” long after I had lost my first language from lack of using it.

Even when they had learnt English my mother and her friends spoke Polish at home, especially when they didn’t want me to understand what they were saying. “Dziewczynka!” (The little girl!) Manka would warn when a dangerous subject was looming among her women friends, so they’d make the smooth switch to Polish, and I would take pains to listen. I had already picked up – by ear – the words of Polish folk songs, and the Polish words of the arias from opera and operetta that my mother was always singing; and I could sing “Jeste Polska Niesginewa” and the rest of the Polish national anthem without understanding one word. Household talk was more interesting, gossip easier to learn, and I could soon understand most of what was being said in Polish provided that it was on an easy domestic topic.

“Sluchaj!” (Listen!) someone would say, and I listened hard. It must have been handy for my parents and their friends to be able to swear cheerfully in front of me without fear that I would pick up bad habits; for, though I knew that “Psiakrew!” “Cholera!” and “Boze Moi!” were swear words, I had no idea what they meant, nor was I in any danger of using the words myself. The language business, like everything else, became more complex after I started school, in February 1930, three years after we had arrived in Australia.

Now the walk from Park Street West across Sydney Road, half-right down Bowen Street, through the railway gates and into Pigdon Street, which we had taken to visit our friends, became even more familiar. My mother had decided that I needed the company of children, that I spent too much time with grown-ups who spoke Polish, and that I was ready for school; so she dressed me in her European idea of a school girl’s outfit (which was a dress covered with an apron, and a wide red ribbon tied in a bow in my hair) and took me by the hand along that well-worn route to enrol me at the closest state primary school. I was four years and two months old – four months younger than the minimum age.

The red-brick and white stucco infants department of the school stood by itself in Pigdon Street, and its headmistress, a formidable lady called Miss Horner, greeted us in a costume and hat, which turned out to be her regular daily outfit. When she took me into the school I bellowed and struggled. I was happy playing by myself, had never been away from my mother (except for those early weeks when she had been in hospital) and with her had travelled across the world to the new land. As I was firmly held back on one side of the white lattice and my mother was sent away crying on the other, I bellowed even louder. Alone and forlorn, I found myself in the unfamiliar and frightening world of Princes Hill Infants School: the family’s bridge into the new world of English language and learning.

How my mother talked the formidable Miss Horner into accepting her underage daughter, I’m not sure. She used to say that she put my age up, but as I was always quite open about my birth date, this may have been untrue. Perhaps she admitted what she’d done later, when I was safely enrolled, or Miss Horner may have made a special case for the immigrant children at her school. Soon after she handed me over to my teacher, a sweet-faced lady called Miss Whitbourne with dark hair arranged in a low bun on her neck, I stopped bellowing and started settling down.

After that first shock, I enjoyed school and remember my earliest schooling with pleasure. I discovered years later from one of my infants school teachers how fortunate we had been at Princes Hill. It was a training school for which the best teachers were chosen (and paid extra) and the school was experimenting with the new American methods of education just introduced into the Victorian Education Department. Music was one aspect of these. Miss Whitbourne played the cello and brought it to school where we sat on hessian mats on the floor, listening to her music. We rested on the same mats each afternoon and drank cocoa from enamel mugs.

In the higher classes, we were taken on excursions to the zoo and collected nature study specimens. My teachers were delighted to teach immigrant children and to meet their parents, for though these parents were all very different from the teachers in language, culture and style, the teachers were not so unsure of their position in the world that they needed to reinforce it by sneering at people unlike themselves. My mother was a cultivated and confident woman and I was outgoing and eager to learn, but I think we would have been made to feel at home by my teachers at Princes Hill Infants School had we each been what my father called “a different cattle of fish.”

I stayed in the pleasant, red-brick-and-stucco infants school from “the bubs” to the end of second class, when we all graduated to Princes Hill State School, a forbidding dark grey stone castle five minutes’ walk away in Arnold Street, Parkville, where it backed onto Princes Park up at the cemetery end. These were the years of the Depression and some of my teachers were profoundly affected by their experiences of teaching poor children in a poor area. I was warmly dressed and had plenty to eat and a comfortable bed, but was aware of a greyness and ugliness about almost everything connected with my four and a half years at Princes Hill.

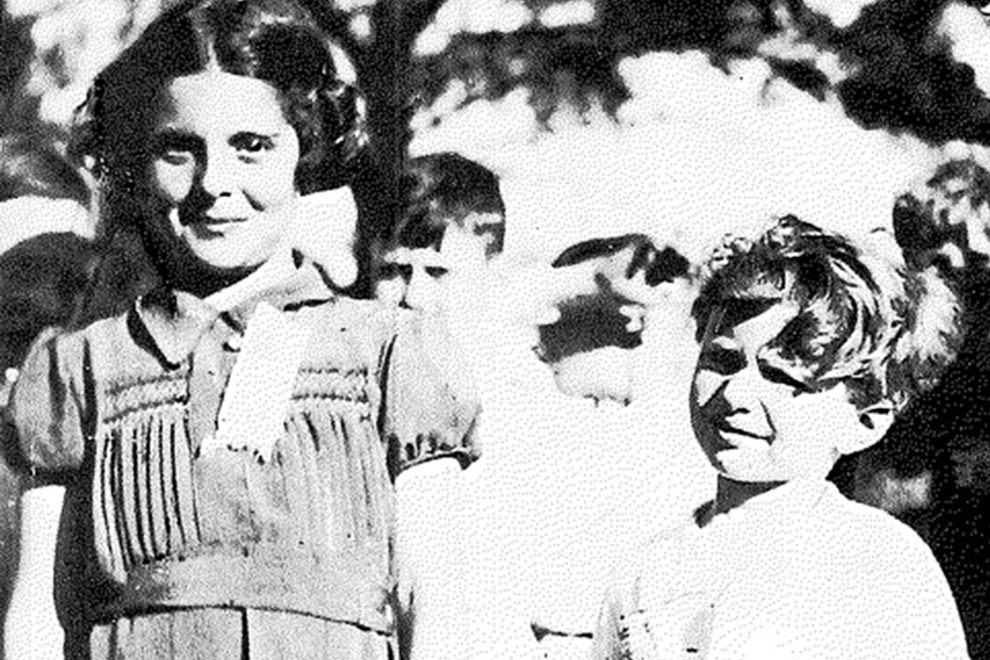

Only three teachers and two of my contemporaries gleam out of the greyness, and two of those teachers were from the sunny red-brick-and-cream-stucco days: Miss Whitbourne and Miss Hughes, also dark but stronger featured, who took me and Ursula, the German girl, home to her parents’ place to stay for the weekend. That was a memorable event. We travelled by train for ages, it seemed, to one of those far-off, leafy suburbs like Camberwell or Malvern, and there everything seemed strange and interesting to me. We sat at a large, brown dining-room table, I remember, cutting out coloured paper. Many years later I discovered that we were three that weekend (not two as I had remembered for almost forty years) and that we were cutting out baskets for the sweets Miss Hughes’s mother made for the church social to which we all went on Saturday night. Homemade sweets and church socials alike were not in my culture, though they were in Norma Carmichael’s, the third girl from Miss Hughes’s class who was there.

The third teacher I remember was a large, blond, statuesque young woman who wore sandals – very unusual in those days – and whom my parents met out of school. An artist and member of the Workers’ Art Club, it was she who was always chosen to represent Britannia and sat, draped in a white Grecian robe, holding a red, white and blue cardboard shield in one arm and a trident in the other, with a real brass fireman’s helmet on her handsome head, the pinnacle of the school’s Empire Day pageant. Around her large, sandalled feet clustered children dressed as colonial subjects, some of us coloured with cocoa to represent Indians and Africans.

At Princes Hill School, it seemed to me that my parents were Europeans whereas every other kid except Ursula (who was a blond, blue-eyed non-Jewish German) had parents who were Australians of several generations. This was not true, I know now from talking lately with Miss Hughes. There was a large minority of Jewish children of immigrant parents, some of whom must have been my home friends, but that was not how it seemed to me. From such an early age I must have aspired to the world that was not mine and, like my father, undervalued what I had. The older I got, the more dearly I realised that my parents were certainly not like others. They were Jews when other kids’ parents were Christian; they were foreigners when other kids’ parents were Australians; they were readers of books when other kids’ dads read the Sporting Globe and their mums read the New Idea. •