I HAVE been involved in British elections since 1948, when I helped out in Labour’s campaign in the North Croydon by-election in south London. We lost. My first Australian election was in 1958. We – the ALP, this time – lost again. On returning to England I worked in every election between 1966 and 1976, being a Labour Party agent in the February 1974 election that led to a “hung parliament.” In the last British election, in 2005, I did grassroots research in English areas stretching from east London to Bradford and Blackburn. My focus was on immigration as an issue and Muslims as political participants. One thing I have learned about elections – you win some and lose some. This week it looks as though we might lose again.

British general elections are normally fought between the three major parties, each of which contests all seats, with minor parties emerging (and declining and disappearing) from time to time. Governments are typically formed from one party only. Since 1945 the Conservatives have held office for thirty-five years and Labour for thirty, and it is these two parties that normally define political issues. Ever since Labour replaced the Liberals as the opposition to the Conservatives in the 1920s, the Liberals have been struggling to redress the balance, with very limited success until the 1980s, when they added the name “Democrats” to their title. Only in the devolved systems of Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland has this simple pattern not held. But 533 out of 650 of Britain’s constituencies are in England, so the two-party system has survived nationally.

British governments deal with a multitude of national and issues, but in general elections these are often reduced to just a few: the competence of the sitting government; the state of the economy and especially of unemployment, health and education; the personality of national party leaders; and a few random issues raised during the campaign, mainly by the media. Since the 1950s that last category has often included debate about the level and origins of immigration and consequent changes in the ethnic composition of the population. These concerns often erupt unexpectedly and the major parties try to sidestep them as too combustible and unpredictable. But they are of great interest to the popular media, with mass-circulation newspapers like the Daily Mail, the Daily Express and the Sun being especially vocal.

The origins of these debates go back over a century. Opposition to large-scale Jewish immigration from the Russian empire led to Britain’s first law controlling inward migration, the Aliens Act of 1905. But while there was considerable prejudice, in practice there was no effective control over immigration. The Irish were British subjects as were all members of the vast and growing British Empire, and until 1962 there was nothing to prevent anyone with that status from entering and settling in the United Kingdom. This included about a quarter of the human race, especially Indians and Africans as well as Australians and Canadians. Their right to enter and settle in Britain was not curtailed until successive changes to the law in 1962 and 1968.

By the 1960s large communities from the West Indies, India and Pakistan were established in London and several industrial cities. Irish immigrants have never been restricted in peacetime and there are normally 500,000 living in Britain (compared with four million in the Irish Republic). Commonwealth citizens enjoyed the same rights as British subjects born in Great Britain, including the vote, as did all their children born in the United Kingdom. Large concentrations of first-generation voters were thus established over time in London, Birmingham and many Lancashire and Yorkshire mill towns such as Bradford. These gravitated towards the Labour Party and created strong political influences in many local government areas.

These arrivals from the British Commonwealth were often directly recruited by employers, but they were not always welcomed by those among whom they settled. Rioting first broke out in West London and Nottingham in 1958, and similar outbreaks have occurred intermittently ever since. The tension also helped in the revival of organisations like Oswald Mosley’s British Union of Fascists (suitably renamed) and later, in 1967, the National Front. The electoral impact of this mood included the loss of the industrial district of Smethwick near Birmingham to a racist Conservative in 1964. The Conservative frontbencher Enoch Powell took up a strong position against Commonwealth immigration and the Race Relations Act in 1968, encouraging a mass movement of support.

Immigration and race thus entered the list of recurring political issues despite the caution of the major parties. While explicitly racist parties in the tradition of the National Front have never won a parliamentary seat, public opinion has remained sufficiently volatile for the main parties to be wary of the issue. Concern was fuelled by serious rioting in London, Lancashire and Yorkshire in the 1980s, by increasing numbers of African refugees from the 1990s and by the impact of Islamist terrorism, including the bombing attack in London in 2005. These issues entered the 2010 election contest through a growing realisation that immigration and refugee policy was dysfunctional and muddled, a fact that even the thirteen-year-old Labour government admitted. The Labour dilemma is that most Muslim, Black British, Indian and African voters and local councillors are party supporters, but the appeal of open racism is most apparent in working-class constituencies, especially those suffering from deindustrialisation.

The heated and sometimes violent nature of British race relations obscures the reality that, on the one hand, the majority of “coloured” Britons were born in Britain and, on the other, that at least half the currently high level of immigration has been from the “Anglosphere” (the United States, Ireland, Australia, South Africa, New Zealand) or the European Union (Germany, Poland, Italy, Spain). Figures for illegal migrants are acknowledged to be seriously inadequate, but according to the last census figures only 7.5 per cent of the British population is overseas-born – one-third the percentage of overseas-born in Australia. Of these, the largest numbers (each 100,000 or more) in 2001 were, in order of size, from India, Pakistan, Germany, the Caribbean, the United States, Bangladesh, South Africa, Kenya, Italy and Australia. Since then there have been large influxes of Africans seeking asylum from collapsing states like Somalia, and Poles and other central and east Europeans taking advantage of free movement within the European Union.

Public perceptions of the link between immigration and a large “coloured” population are based on three phenomena: the very high concentrations in London, where a quarter of its population of seven million was born overseas; the growing number of children and grandchildren of Indians, Pakistanis, Bangladeshis and West Indians (the so-called Black British); and the recent spread of immigrants into areas that have not previously experienced any significant immigrant arrivals. The half-million Poles who have come to Britain, for example, have gone to rural and provincial areas like the East of England, Northern Ireland (and the Republic) and Scotland. Refugees have been officially dispersed to places that had no previous experience of immigration.

On top of this, neither the political parties nor their local and national governments have done much to explain what is happening. Asylum seekers are still wrongly described as “illegal” and European Union citizens are blamed for taking jobs from the British, which they are legally entitled to do. Tensions are exacerbated by a national level of 8 per cent unemployment and higher rates in former industrial cities and parts of London.

AGAINST this background, the major political parties are reluctant to enter the debates and controversies dominated by marginal racist organisations and the irresponsible end of the mass media. The three major parties all agree that immigration policy needs reform, with Labour having to explain why it did so little during the past thirteen years. In their official material all three parties discuss immigration under the heading of “law and order,” with the relevant section on the Labour manifesto titled “Crime and Immigration.” Treating immigration as a policing issue has left it under the control of the vast and complex British Home Office. The Labour manifesto refers throughout to “fairness” but moves from “terrorism and organised crime” direct to “strong borders and immigration control.” Claiming that “our borders are stronger than ever,” that all visas are biometric and that border control will be counting people in and out, Labour takes credit for asylum claims being down to early 1990s levels. Great emphasis is placed on the “new Australian-style points based system,” which will limit immigration from outside the European Union to skilled migrants with English competence. Those fortunate to secure citizenship will qualify after a minimum of five years and a test of British values and traditions.

All of this is acceptable to the Conservatives – except Labour’s failure to have done it already. What both parties leave out is any reference to disadvantages or any reference to multicultural settlement policies. The exceptionally long Conservative manifesto deals briefly with immigration under “Attract the Brightest and the Best to Our Country” and strongly support continued immigration, but at the lower levels of the 1990s. An annual cap would be set on non–European Union migrants. A new Border Police Force would be set up, English knowledge would be required for anyone coming to be married from outside the European Union, and the student visa system would be tightened.

A social cohesion program is promised under the “Community Relations” heading. This calls for national integration, English language as a priority for all communities, school history to promote “a proper narrative of British history,” and a National Citizen Service for sixteen-year-olds, and supports Combined Cadet Forces. This assimilative program will also tackle “unacceptable cultural practices” such as polygamy, khat chewing, forced marriages, extremism, bigotry and hatred. Muslims are not mentioned by name, but are presumably not included under “faith groups” that are to be encouraged. There is no mention of the hijab.

Of the three, the Liberal Democrats are the only party to separate legal control from humane considerations. But even their manifesto spends some space under “Your Community” talking about policing before getting to “firm but fair” immigration policies. According to the Lib Dems, the system “is in chaos after decades of incompetent management.” Like the other two parties, they want a National Border Force with police powers and exit checks and the deportation of criminals and people traffickers. But they depart from that view in wanting an amnesty for law-abiding residents who have never had correct papers and have lived in Britain for over ten years. The Lib Dem position on refugees is markedly sympathetic, removing control from the Home Office, allowing asylum seekers to work, removing children from detention and not returning refugees to states likely to persecute them. All of these would bring Britain more closely in line with the UN Refugee Convention (and closer than is currently the case in Australia).

The Green Party of England and Wales does not oppose immigration or the European Union and “seeks to change negative attitudes and stereotypes associated with refugees.” It has two members in the European parliament and two in the London assembly, and its Scottish counterpart has two members in the Scottish parliament.

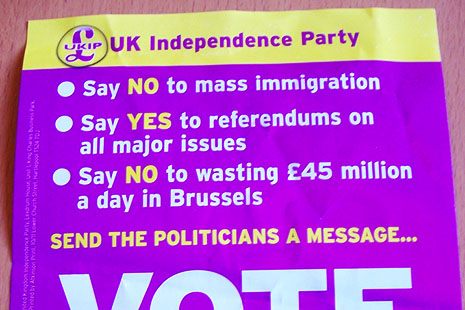

The extremist fringe, meanwhile, is divided into rival organisations which between them are fielding a larger number of candidates than ever before. This will fragment the so-called “patriotic” vote, making it very unlikely that anyone will be elected. Rivalries are most acute between the British National Party, or BNP, and the UK Independence Party, or UKIP, both of which have had seats in the European parliament since 2009 as a result of proportional representation. With only seventeen candidates in this election, the National Front (which aims “to save our Race and Nation”) is no longer an important player, having lost most of its previous support to the BNP. UKIP does not have the fascist origins that can be traced through the National Front and the BNP; it is best seen as a dissident middle-class breakaway from the Conservative Party’s right wing. But it is running candidates in almost all the seats being contested by the BNP and will take votes from the same people.

UKIP’s priority is total withdrawal from the European Union. Its manifesto, Empowering the People, claims that Britain “has lost control of its borders.” Control can only be regained by leaving the European Union, tripling the size of the UK Borders Agency, freezing immigration for settlement for five years and repatriating illegal immigrants. After the five-year freeze, all immigration for settlement should be on the strictly controlled points system used by Australia. All asylum seekers should be held in “secure and humane centres,” according to the party, and all travellers to Britain must obtain a visa overseas. “Bogus educational establishments” should be targeted. The doctrine of muticulturalism should be abandoned by all publicly funded bodies, the Human Rights Act should be repealed and Britain should withdraw from the European Convention on Human Rights. Much of this is close to conservative mainstream discourse in Britain and Australia. UKIP is running 572 candidates and is by far the most heavily funded of the minor parties.

The BNP policy claims that immigration is out of control, leading to higher crime rates, increased housing costs, lower wages, higher unemployment, a loss of British identity and a more atomised society. The solution is to deport all “two million” illegal residents, review all grants of residence and citizenship, offer grants to those of foreign descent who wish to leave, stop all new immigration and reject asylum seekers who have passed through another safe country. “All the British National Party wants is the right to be British,” says the party. Like the National Front and the English nationalists it flies the St George flag and – agreeing with Conservative Party policy on “Community Relations” – wants his saint’s day (23 April) to be a national holiday.

Then there are the two English nationalist parties, the English Democrats and England First. The Democrats claim that they welcome anyone who supports “the English way of life and the values and beliefs of England.” They are particularly hostile to the Scots who “dominate” politics – a novel prejudice. Multiculturalism should be defunded and resources transferred to celebrating St George’s Day. England should also withdraw from the UN Convention on Refugees and “bring mass immigration to a complete end.”

England First goes further, favouring “voluntary repatriation of non-Europeans back to their lands of ancestral origin” and “the abolition of all non-European faiths and religions.” It works closely with the National Front and a strongarm group the English Defence League, but is nominating only for local government contests in Lancashire and Stoke-on-Trent.

UNUSUALLY, British politicians and bureaucrats have finally acknowledged the muddle in immigration policy and advocated adopting an “Australian” approach. This will require a points system emphasising skills, like the one used in Australia since 1979, and a registration system for arrivals and departures, as in Australia, the United States and many other countries. Accurate figures of illegal overstayers can then be produced and some, at least, tracked down. None of this will apply to the Irish, to other European Union citizens or to asylum seekers. It should alleviate anxieties about the muddled state of immigration policy and will be implemented by whichever party wins office on 6 May.

Important problems will remain and differences from Australia will persist. While human rights, anti-discrimination and multicultural policies have been in place since the 1970s, race relations in Britain are undoubtedly more acutely troubled than in Australia. “Coloured” residents now have social and political domination in several London boroughs, in Bradford, Leicester and parts of Birmingham and Manchester. This influence is often resented by those the extremist groups call the “indigenous” English. The Muslim population, at 2.7 percent, is not large, but is proportionally twice that of Australia. Occupying an area the size of Victoria, England has a population density 150 times Australia’s. The prospect of adding any more people has already influenced public debate in the 2010 election, quite apart from the ever-present “race problem.”

Regardless of who wins this week’s election there is likely to be more rigorous control over immigration, insofar as that can be consistent with Britain’s obligations as a member of the European Union. Should the Liberal Democrats ally with either of the major parties they may prove a modifying influence on attitudes towards refugees. But neither Labour nor the Conservatives have committed themselves to multiculturalism. David Cameron, the Conservative leader, is on record as being quite critical of that approach. Whatever happens, the extremists will not be satisfied. •