IN SEPTEMBER 1991, Paul Keating, biding his time on the backbench for another tilt at the prime ministership, gave a public lecture at the Australian National University. I was in the audience with a colleague who was much taken by the former treasurer. During the lecture, she took off one of her high heels and whispered wistfully, “I feel like throwing it onto the stage.” Her motivation was very different from that of Muntader al-Zaidi, the Iraqi journalist who threw a shoe at George W. Bush last year. She was a senior academic of frighteningly sharp intelligence, and here she was: gushing like a love-struck teenager over somebody who, I thought, wasn’t even particularly good-looking, and behaved more often than not like a bully.

It had been a long time since I was full of unrestrained admiration for a politician. When I was fourteen, I put up election posters of Willy Brandt in my bedroom and – much to the embarrassment of my parents – in our hallway. Brandt was West Germany’s chancellor at the time, the first Social Democrat to hold that job in the postwar period.

I can’t recall the emotions I experienced when the Social Democrats won the 1972 elections. But I doubt that I could have been any more elated than at the moment a couple of months ago when the first American television network predicted that Barack Obama would carry the crucial state of Missouri, which seemed to seal his victory in the presidential elections. In the past few months I have been as gushing about Obama as my colleague was about the Placido Domingo of Australian politics.

I would like to believe that my admiration for the next US president has little to do with his rhetoric or his charm or his looks, or with the ineptitude of the incumbent. It doesn’t even have much to do with his political program. My love affair with Barack Obama began early last year when I was stuck at Melbourne airport, waiting for a delayed flight, and picked up a copy of his Dreams From My Father. I did not expect much from the book except that it would help me to kill time. I expected it to be self-serving: the work of a man staking a claim for a role in American public life, packaged as a variation on the rags to riches fairy tale.

Obama was thirty-three when he wrote that book. In Australia, most of the people who publish “autobiographies” at such a tender age are either footballers or cricketers. Their books are of interest only to those mad about sport. Although they are often ghosted, these texts are hardly ever renowned for the quality of their prose. They tend to have a short shelf-life. Obama’s book is not just well written; at times, its language is poetic. Admittedly, it could have been more economical. In the preface to the 2004 edition, Obama writes: “I have the urge to cut the book by fifty pages or so,” and sometimes I wished he had followed that urge.

Perhaps most surprisingly, the book is remarkable for its maturity. Its protagonist is anything but mature: he is “full of resentments and desperate to prove [his] place in the world” and “living out a caricature of black male adolescence, itself a caricature of swaggering American manhood.” The mature Obama remembers the “blood rush of a high school brawl. The swagger that carries me into a classroom drunk or high, knowing that my teachers will smell beer or reefer on my breath, just daring them to say something.” Dreams of my Father is about a young man who is unsure about himself and the world.

The confidence and sense of self that Obama acquires in the course of his life (and of writing the book) does not manifest itself in lessons dished out to others. He is not preaching to his readers; in fact, his story does not have a moral of practical use to them. In that sense, Obama’s description of his journey is a soliloquy.

An autobiographical text about a thirty-three-year-old finding himself could easily be self-indulgent. It could easily make readers squirm. It doesn’t in this case because, in spite of his earnestness, Obama managed to find a tone that is light and full of self-irony. He seems amused about aspects of his masculinity and race consciousness, and is at times even self-deprecating. He shares with his readers awkward moments, defeats (there were many during his time as a community organiser in Chicago) and silly mistakes. That makes him likeable as a person. His ability to put himself on the line by being brutal in his self-assessment, while at the same time keeping things in perspective and forgoing the temptation to treat himself as the centre of the universe may also become one of his most valuable – and endearing – traits as a president.

In the book, Obama is more generous when it comes to the weaknesses of others than when it comes to his own. Dreams from my Father is also about his immediate family. It is about his larger-than-life father, and it is about the debt he owes to three remarkable women: his mother, his maternal grandmother, and his half-sister Auma. Interestingly, the book suggests that his most important role model may have been neither of the above, but his maternal grandfather, who at the same time embodied a life path that both Obama himself and his mother wanted to avoid.

Obama wrote his memoir-cum-bildungsroman fourteen years ago, before he became a politician. Dreams from my Father could not have been written last year – unless, of course, he had had a ghost writer to help him, and unless the manuscript had been vetted by political advisers and focus groups. President Obama will not be able to make the same choices as Barry, the college student, or Barack, the community organiser. The book may not hold the key to a future President’s policies. But it makes me hopeful because it tells me something about the person who will be grappling with difficult choices that affect my life almost as much as that of somebody living in Chicago.

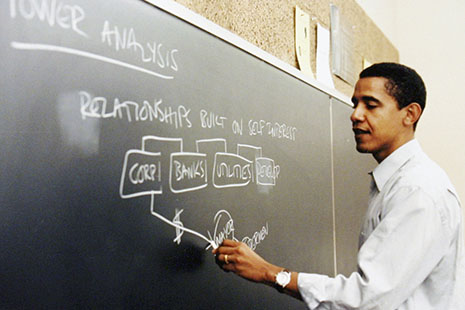

The person who reveals himself in Dreams of my Father comes across as genuine and honest. He is somebody who is aware of his own shortcomings. He is able to reflect on his behaviour as much as on that of others. As president, he might just remember some of what he knew when he wasn’t yet a powerful politician: when he knew about the patience and doggedness of a certain kind of power: a power that “could outwait slogans and prayers and candlelight vigils.”

Obama is also somebody who knows about the enabling and destructive forces of fictions, of fantasies and of dreams. Right now, he is riding on the back of one of those dreams. He writes that stories told by his maternal grandparents “gave voice to a spirit that would grip the nation for that fleeting period between Kennedy’s election and the passage of the Voting Rights Act: the seeming triumph of universalism over parochialism and narrow-mindedness, a bright new world where differences of race or culture would instruct and amuse and perhaps even ennoble. A useful fiction, one that haunts me no less than it haunted my family, evoking as it does some lost Eden that extends beyond mere childhood.” I put my trust in somebody who is only too aware of the fictionality of such stories, yet willing to let himself be inspired by them.

In Obama’s family, it was his Kenyan father who summoned those fictions – “as if Dr King had never been shot, and the Kennedys continued to beckon the nation, and war and riot and famine were nothing more than temporary setbacks, and there was nothing to fear itself.” In today’s world, Obama himself will be able to summon similar fictions. We should be as wary of dreams as Obama is in his book. But we also need them, and their energies, as much as he has needed them in his own life.

My love affair with Willy Brandt did not last nearly as long as the time that passed between Kennedy’s election in 1960 and the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act. By the time Brandt resigned in 1974 I was already deeply disillusioned because he hadn’t done half of what he had promised. But I never admired Brandt as a person. Rather, I was in love with the A1-size face I had pinned up on my bedroom wall, and with the slogans that adorned this and other election posters.

Some in the American Left are anticipating that they will be disappointed as quickly as I was after Brandt’s re-election in 1972. They are already grumbling: that he has appointed conservatives to key positions, and that he has been toning down his reformist rhetoric. I am willing to put my trust in the next American president. While I am as anxious for substantial change as many of those now voicing or anticipating their disappointment, I believe the capacity to effect far-reaching change is also dependent on a policy maker’s character, intellect and instincts. The author of Dreams from my Father strikes me as somebody with the right character, intellect and instincts. He may just be able to pull it off. •