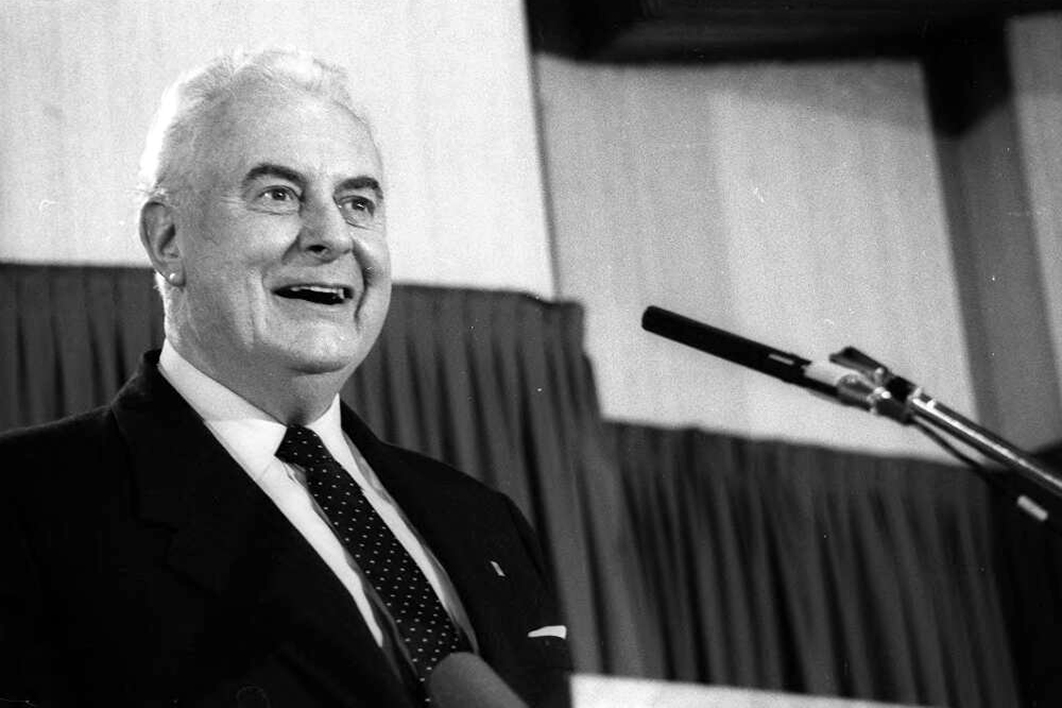

To see the Whitlam government as a product of the 1960s is so conventional, so obvious and so banal it hardly seems worth saying. The government was elected in 1972; how could it not come out of the decade that preceded it? But those who see Gough Whitlam and his government in this light mean something more. Whitlam becomes a symbol of the Australian 1960s, his government an expression of the “time of hope” between Robert Menzies’s retirement in 1966 and Whitlam’s triumph in 1972.

This reading of the Whitlam government’s place in history is a first cousin of the criticism that it tried doing too much, too quickly. The government’s tragedy is supposedly that, while exuding 1960s optimism, it was forced after the oil crisis of 1973 to become a 1970s administration, one more concerned with crisis management than implementing social democracy. Australia’s 1960s are then seen to have officially ended in 1975, with the dismissal.

These orthodoxies are not completely false as history but they capture only part of the Whitlam government’s relationship to the 1960s. In his memoirs, Whitlam saw his own government in a longer timeframe – a product of the policy development of the late 1960s and early 1970s certainly, but also the result of a much longer engagement between the Labor Party, the voters and the Constitution. And this tale has also sometimes been recounted as a personal odyssey, in which a young second world war airman becomes actively involved in politics by advocating enlarged powers for the federal government at the 1944 Powers Referendum, and a rising lawyer and politician becomes aware, during the 1950s and 1960s, of the limitations and possibilities inherent in the constitution for the achievement of a social-democratic Australia.

Jenny Hocking has traced this story in the first volume of her fine biography of Whitlam: she stresses the continuities between the Curtin and Chifley era and the vision articulated with increasing clarity and impact by Whitlam during the two decades that preceded 2 December 1972. This emphasis on continuity rather than rupture, however, raises awkward questions for those who assume a seamless transition between 1960s protest and Whitlamite social democracy.

There are other reasons to question this link. The remembered 1960s are usually the late 1960s, especially in Australia, where there was no “dream hero” like John F. Kennedy to epitomise the spirit of a new decade. Arthur Calwell, while still respected for his role as postwar immigration minister, was hardly fit for purpose. It is the turbulence and protest of the Vietnam era, the later 1960s, that are recalled: a time of demonstration and revolt. But it is rather difficult to find a place for Whitlam here. Unlike Jim Cairns, later his deputy prime minister, and Tom Uren, his urban and regional development minister, Whitlam was not prominent in street protest.

Indeed, Hocking suggests he was rather unsettled by it, for “as a determined believer in the institution of parliament and the practice of parliamentary democracy, he would not condone any suggestion that the will of the people expressed through the ballot box should be usurped by the will of the people expressed through mass protest.” The more expressive, less institutionalised politics of the later 1960s and early 1970s had little appeal for him, whereas for Cairns it increasingly weighed like a nightmare – or a daydream – on the brain of the living, offering a utopian alternative to Max Weber’s “strong and slow boring of hard boards.”

What was true of Whitlam himself was also true of most of his ministers. The only sense in which these men might be considered 1960s radicals is that quite a few of them were “radicals” (of sorts) in their sixties. Clyde Cameron, just a few weeks from this personal landmark when he was sworn in as labour minister, was an ex-shearer who cut his political teeth in Adelaide’s Botanic Park advocating a tax on the unimproved value of land for the Henry George League. Here were roots in the political culture of early Labor – the single tax had been a significant influence on the party in the 1890s but it is hardly an idea usually associated with 1960s radicalism! The youngest member of the first full ministry was Bill Hayden, who was not quite forty. The oldest, Rex Connor, at almost sixty-six was the only Edwardian in cabinet, but the majority of the first Whitlam Ministry was born before, during or immediately after the Great War.

Like David Meredith in My Brother Jack, many of these men – there were no women in caucus, let alone in cabinet – would have experienced the first world war as a shadow over their early childhoods. So, to some extent, might the dozen ministers born in the 1920s. But it is the Great Depression, the second world war and the Labor Split of 1955 that are likely to have exercised the most direct influence over their political formation. The affluence of the era following the mid 1950s must have been as politically unsettling as it was personally gratifying for a generation bred on austerity and self-denial.

The experiences of this generation – all but two of them born between 1910 and 1930 – might be usefully contrasted with those whose idealism this government is so often seen to represent: the baby-boomers most commonly associated with 1960s radicalism and revolt. A young man born in, say, 1947 will have qualified to vote for the first time in a federal election in 1969 (the voting age was then twenty-one). He would have no recollection of the Labor governments of the 1940s; rather, his childhood will have coincided with Robert Menzies’s long reign, in which the prime minister will have seemed not so much a father as a grandfather figure.

But even while our hypothetical male baby-boomer has had the good fortune not to face economic depression or global war, he will have been liable to a call-up for service in Vietnam. If he were one of the still small but rapidly growing minority attending university, he will have done so between about 1964 and 1968, an era of rising campus radicalism coinciding with the escalation of that war. He will typically have married in his mid-twenties. With a substantial mortgage, he’ll want job security and as high a wage as possible. With a home in the suburbs, he’ll be interested in how long it takes to get to and from work, and how good the sporting facilities are in his rather sparse outer suburb.

Women, on average, married at twenty-two in the early 1970s; more than for men, full adulthood coincided with both marriage and their first vote. A woman born in, say, 1950 will have been much more likely than her mother to have received an extended high school or even some tertiary education. She will most likely have experienced the world of work both before and after her wedding day. She might even, before her marriage, have taken advantage of reliable contraceptives such as the pill, which was increasingly available to single women. She will almost certainly have used contraception after her marriage, possibly to extend her time in the paid workforce and so save for the deposit on a house.

Our hypothetical female baby-boomer has every reason to support the Labor Party policy of equal pay for equal work not just as a matter of principle, but because it will help allow her acquire her own home and start a family. She might have begun thinking about where they will go to school, and whether she’ll be able to face consigning her children to the miserable demountables she spotted being erected the other day. Yet, having read a book called The Female Eunuch on her last holiday, and meeting some women’s libbers from the university, she might now be in two minds about whether a rapid plunge into marriage and motherhood is such a good idea. But perhaps affordable childcare will allow her to continue working after the children come along? It would be great if someone would connect the sewage. Her first vote will be at the 1972 election.

The idea of a “generation” can be misleading because it overlooks distinctions of class, ethnicity and region and can both exaggerate and stereotype the differences between people who belong to different age-groups. Returned servicemen and their families – indeed, even relatively well-off families such as that of young Gough and Margaret Whitlam – experienced many of the same kinds of challenges and difficulties I have identified with our two baby-boomers. But men and women who started families between 1945 and 1972 had something in common that distinguished them from older Australians – they enjoyed full employment and a material affluence virtually unimaginable to their parents and grandparents.

Whitlam’s achievement was to speak so eloquently to this experience, and to devise policies appropriate to it. He did not bemoan affluence, nor did he accept the view – one that rattled around “informed” commentary of the 1960s – that better economic times and declining class consciousness had rendered Labor redundant.

Whitlam, of course, was not unique in challenging this idea, either in Australia or internationally. While much of the commentary on he and his government is characterised by a kind of national self-containment, there is much to be said for viewing Labor Party transformation of the 1960s in a transnational context. The Whitlam government is related to the Australian sixties in similar kinds of ways as the Pearson and (especially) Trudeau governments to the Canadian 1960s and the Wilson government to Britain’s 1960s. The larger historical frame was set by the Kennedy era in the United States and the noble, thwarted ambitions of Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society.

The 1960s in the English-speaking world saw two phenomena that can seem to pull in different directions. On the one hand, there was renewed stress on the value of the local and regional; on the other, a demand that the local and the regional be made to conform to appropriate national and international standards. The paradox of this simultaneously enhanced and reduced status for the regional is to be explained by a radical reconceptualisation that took place in understandings of the relationship of the local and regional to the national and international.

The Whitlam government emphasised the value of regionalism, famously in relation to the idea of Albury-Wodonga as a growth area, but more generally in its policies on cities and northern development. The Australian Assistance Plan, itself consciously modelled on Canadian precedent, sought the delivery of a range of social services at the regional level, through a partnership of the federal government with newly minted regional councils and locally based voluntary groups. Yet Whitlam was equally insistent that one’s location, no more than one’s class, ethnicity or gender, should determine the level of access a citizen enjoyed to government services. Social-democratic modernity was understood as allowing for diversity within a broad set of norms defined and enforced by a federal government guided by qualified experts and engaged citizens. But the government needed to be clothed with the authority and the revenue to enforce such standards because no other authority in Australia was capable of doing so.

This attitude to the role of the national government was “fully in tune with the spirit of the age” – to use Whitlam’s own words. In Australia, as elsewhere in the west, parochial attitudes and justifications for behaviour repeatedly found themselves confronted with national and international standards. The trend is especially evident in the area of race, where from the early 1960s the White Australia Policy and policies concerning Aboriginal people came under domestic criticism – usually from well-educated middle-class people – partly on the grounds that Australia would become an international pariah like South Africa unless it mended its ways. Whitlam identified wholeheartedly with this line of argument in his policy speech of 13 November 1972 when he memorably declared that “[m]ore than any foreign aid program, more than any international obligation which we meet or forfeit, more than any part we may play in any treaty or agreement or alliance, Australia’s treatment of her Aboriginal people will be the thing upon which the rest of the world will judge Australia and Australians.”

The desire to overcome parochialism was evident in a range of fields. Yet, again paradoxically, a celebration of the urbane, the cosmopolitan and the international was accompanied by a more assertive post-imperial nationalism. In this respect, the Whitlam government took some inspiration from Lester Pearson and Pierre Trudeau in Canada – even allowing for the very different problems they faced in light of Quebec and US domination. But the battle against the parochial was not confined to politics of national identity; there was hardly an area of policy that could not be rationalised in terms of its ability to drag Australia into the modern world, or to overcome its backwardness.

Interestingly, this language was not confined to former settler colonies such as Australia, New Zealand and Canada; a similar language was being used in Britain itself by modernisers of one kind or another, including social democrats working in a similar spirit to Whitlam. Anthony Crosland, for instance, complained of British conservatism, complacency, parochialism and backwardness. He looked forward to a modernisation that would make his country more like the United States and Sweden.

Here, the Whitlam project intersects with broader developments in social-democratic thinking. In the 1950s, British socialists such as Crosland argued that the declining power of business, growing equality, full employment, the welfare state, rapid growth and rising working-class affluence had rendered much previous socialist thinking redundant. Ownership of capital now mattered less than who managed it. In these circumstances, the old preoccupation with nationalisation made little sense. Even greater equality could be achieved through progressive taxation and the education system, while socialists needed to turn their attention to what he called “deficiencies in social capital… ugly towns, mean streets, slum houses, overcrowded schools, inadequate hospitals, understaffed mental institutions, too few homes for the aged, indeed a general, and often squalid lack of social amenities.” In an age of abundance, socialists would also necessarily give attention to what would become known as quality of life issues: the environment, culture and civil liberties, “personal freedom, happiness, and cultural endeavour: the cultivation of leisure, beauty, grace, gaiety, excitement.”

Crosland met Whitlam when he visited Australia in 1963. “I’d be careful about that chap Whitlam,” the British visitor whispered to a young John Button during a function in Melbourne, “He could be dangerous.” “Why do you think that?” Button asked. “Well, I suspect he’s highly intelligent,” was Crosland’s reply in an Oxford drawl that even his Australian admirers found irritating. When, many years later, Whitlam was asked what effect Crosland had on him, his reply was “bugger all.” Yet the similarities between Whitlam’s version of social democracy and the ideas being developed by British revisionists in the 1950s and 1960s seem all too obvious. Whitlam’s speechwriter, Graham Freudenberg, recounts in his memoir that his own thinking was influenced by contemporary debates in British socialism.

All the same, it is true that revisionism had a limited impact in Australia of the 1950s – that it was in many respects a casualty of both the 1955 Labor split and the party’s notorious anti-intellectualism. In these circumstances, any criticism of Labor orthodoxy was seen through the prism of bitter political rivalry. Heinz Arndt, a Canberra academic economist and Labor Party member, provoked a storm and even threats of expulsion when, in his 1956 Chifley Memorial Lecture in Melbourne, he advocated a mixture of Keynesian and “revisionist” ideas, notably that Labor should abandon support for “nationalisation as a panacea for all our ills” and instead concentrate on promoting economic growth and greater equality through “public finance, progressive taxation and government expenditure.”

In the 1960s these kinds of ideas gradually became Whitlamite orthodoxy. Whitlam himself increasingly argued that Labor needed to cease using the Australian constitution as an “alibi” for failure to implement its policies. He advocated constitutional reform but he also pointed out that existing arrangements would allow the party to fulfil its fundamental goals. Much like Crosland, Whitlam argued that it was the role of government to create the social goods that people could not create for themselves. And he also incorporated a new progressivism that emphasised similar issues to those flagged by Crosland. More generous educational provision, for instance, was central to Whitlam’s thinking, as was a national health service, something enjoyed in Britain since the late 1940s.

Whitlam also emphasised the need to overcome race and sex inequality, and to achieve better environmental protection and town planning, a more generous and rational system of welfare provision, and the promotion of the arts, literature and national identity. He advocated a more independent, Asia-centred foreign policy and an overdue independence for Papua and New Guinea. All were Australian responses to Australian problems. But the proposed solutions drew on relevant overseas experience and expertise, for most of these issues were also local manifestations of policy challenges with which progressives, socialists and “liberals” (in the North American sense of the term) were grappling in other places.

In the Australian context, Fabianism needs to be given its due in the emergence of this new progressive politics. Arndt, whom we have already noticed, was an active Fabian in both Sydney and Canberra in the late 1940s and early 1950s, a period that also saw the emergence of Fabian societies elsewhere. These gained their inspiration from the famous society founded in Britain in the 1880s. The Victorian Fabian Society has been the most successful – with a continuous existence since 1947 – but it was almost moribund in 1960 when revived by a young speech therapist, Race Mathews. Closely aligned with the Melbourne University ALP Club, the society flourished and soon boasted several hundred members.

Mathews met Whitlam in 1961 at a Victorian Fabian Society meeting and there would be regular contact between the Victorian Fabians and Whitlam throughout the decade. Whitlam used the Fabian Society as a forum in which to set out his ideas for Labor Party modernisation, and the Fabians formed part of the network on which he depended for policy advice, links to the universities and professions, and even personal staff: all three of Whitlam’s private secretaries of the 1960s and early 1970s – John Menadue, Race Mathews and Jim Spigelman – had been involved in Fabian organisations in their respective cities of Adelaide, Melbourne and Sydney.

One reputedly important policy intervention by Victorian Fabian intellectuals was the contribution of Mathews and David Bennett, an educationist and grandson of John Monash, to Labor’s schools policy. They drafted the proposal for a Schools Commission circulated at the party’s 1966 national conference, and which later formed the basis for the party’s needs-based approach to funding. Their ideas were further developed in a later Fabian pamphlet.

Hocking’s account of Whitlam’s office in the 1960s and early 1970s gives the impression of a cross between a university department and a Fabian-style think tank. As Mathews himself put it, “Whitlam attached overriding importance to research, and insisted that policies should be justified in depth with facts.” Yet Whitlam’s Fabian emphasis on research as the basis of policy has had surprisingly little impact on the impression that his government failed because it acted with undue haste. Whitlam “instinctively and unceasingly sought expert advice” and, besides his informal networks, the development of policy committees within the party itself had provided opportunities for “experts” to contribute to policy formulation.

The Victorian Fabian Society became entangled in the factional politics of the Victorian Labor Party. From 1965 there was an overlap of personnel and ideas between the Fabians and the Participants, a group of moderate Victorian Labor members which became the centre of organised support for Whitlam and opposition to the hard-left dominated Victorian Central Executive, or VCE. John Button, later a federal senator and Labor minister, was active in both and Mathews, although not a Participant, was by the mid-1960s an opponent of the executive.

The extent of the connections between Whitlam and prominent Fabians only underlined the sense of the Fabian Society, in its growing emphasis on issues such as racial injustice, education and the environment, representing a rival vision of socialism to the Victorian old guard. In 1970 David Bennett, who had been a supporter of the VCE (and was believed by an ASIO case officer in the early 1960s to be “an active member” of the Communist Party), gave his support to federal intervention against the VCE and, in his capacity as Victorian Fabian Society president, ventured the opinion that a majority of Victorian Fabians would endorse his position.

The combination of rationalism and idealism that underpinned both Whitlam’s program and Fabian mobilisation was closer to the temper and preoccupations of early 1960s progressivism than the later, more spectacular expressive politics associated with the New Left and the social movements. The implications of this point for how we remember the Whitlam government today are profound.

In the 1980s and early 1990s, there was a tendency to dismiss Whitlamism as a failed venture beside the much more professional, pragmatic and considered reformism of Hawke and Keating. By way of contrast, in recent years, the arduous trials of the Rudd and Gillard governments have provoked some nostalgia and a measured admiration for a reformist government that practised conviction politics and left a significant and enduring legacy.

Both of these understandings, however, are historically unsatisfying because each tears the Whitlam phenomenon from its essential 1960s context. The Whitlam government had the “wind of change” in its sails. But the cyclones of the late 1960s and early 1970s did not matter quite as much as the gentler breezes that had begun blowing in the 1950s and early 1960s. The rock on which it was wrecked was the less expansive possibilities of the 1970s. •