As the world remembers the end of the Pacific war, many stories will be told of momentous events and remarkable lives. But perhaps only one, left by the Australian war correspondent and novelist George Johnston and American correspondent James Burke, will take in the world’s highest peaks, arcadian landscapes, mythical monasteries and Living Buddhas.

Johnston is often remembered today, for the decade he and Charmian Clift spent at the centre of a colony of expatriated writers and artists on the Greek island of Hydra in the 1950s and 60s. This notable example of postwar bohemianism preceded Johnston’s triumphant return to Australia in 1964 amid the success of his widely admired novel, My Brother Jack. It was the first instalment of the autobiographical Meredith Trilogy that cemented his place among Australia’s great mid-century writers.

Johnston had first attracted attention after being appointed a war correspondent with the rank of captain in 1941. He built his reputation with action-filled accounts filed from the frontlines of New Guinea, and then spent time in the United States, the Middle East, Europe, India and finally China, from where he covered the second Sino-Japanese and Pacific wars.

From the moment he arrived in mid-1944, Johnston was fascinated by China. A quick learner with excellent journalistic instincts, he rapidly acquired the knowledge of Chinese history, politics and culture reflected in his dispatches. He was also well-placed to report on the epoch-defining conclusion of the Pacific war following the cataclysmic destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki — or he would have been if he hadn’t embarked on an intrepid personal quest through Tibet’s high mountains in search of the fabled monastery of Shangri-La.

Johnston’s adventure was driven by a need to replenish his war-damaged spirit. Although China enthralled him it also delivered the most confronting experience of his war service. In a personally devastating episode in late 1944 he had followed refugees fleeing the southwest city of Kweilin through famine-stricken country ahead of a Japanese advance. Tens of thousands died in fields and on roadsides. This encounter with massive civilian death left him burnt out and soul-sick.

Johnston hoped for recovery in neighbouring Tibet, whose mysteries fascinated the inquisitive journalist. In early 1945 he reported that wartime reconnaissance was discovering “unsuspected geographical features… where China and Tibet come together in a Disney phantasy of incredible mountains and untrodden gorges.” Tibet crystallised in Johnston’s imagination as a sanctuary, the place “least touched by all the years of the war.”

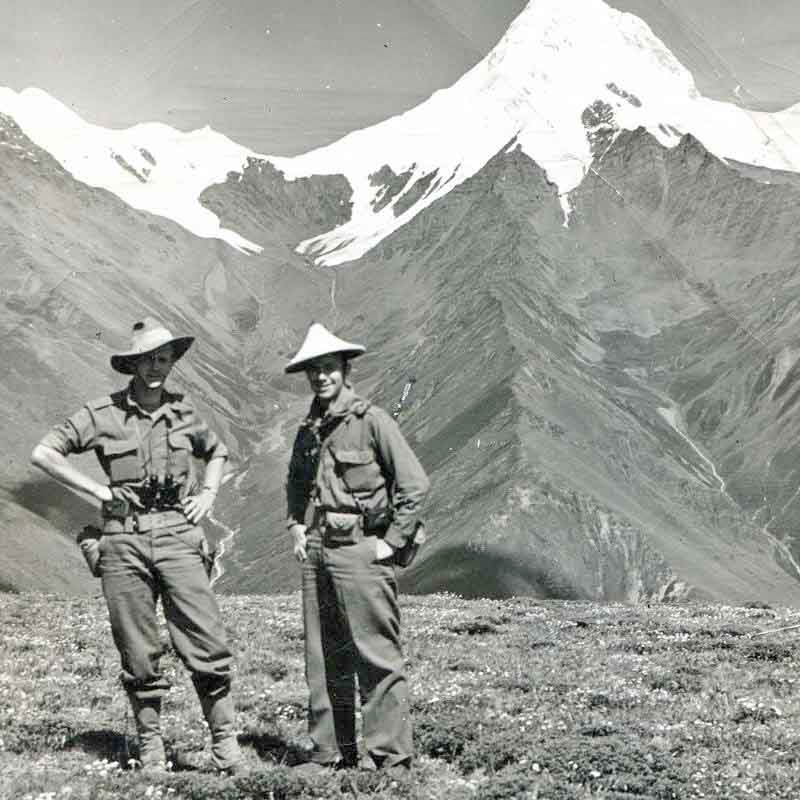

Feng Liu-lu, Johnston and Minya Konka (Gongga Shan), July 1945.

Another factor was also driving Johnston’s fascination. He had read James Hilton’s 1933 novel Lost Horizon, arguably the most influential utopian novel of the twentieth century. Lost Horizon featured the imagined Shangri-La lamasery, a monastery for Buddhist lamas. Hilton described Shangri-La and its surrounding valley as a beautiful, fertile, immaculate place with kindly, gracious, long-lived and peace-loving people uninterested in worldly goods. Crucially, he claimed that Shangri-La could heal Westerners damaged by modernity — a last-chance utopia in a world benighted by war.

Rumours had reached Johnston that Hilton’s Shangri-La was based on the lamasery of Konka Gomba. At an altitude of 13,000 feet, Konka Gomba had for eight centuries clung to the flanks of Minya Konka (known in China as Gongga Shan), at 24,000 feet the highest peak on the Tibetan plateau. If he could find a way into Tibet, Johnston resolved, he would go in search of Shangri-La.

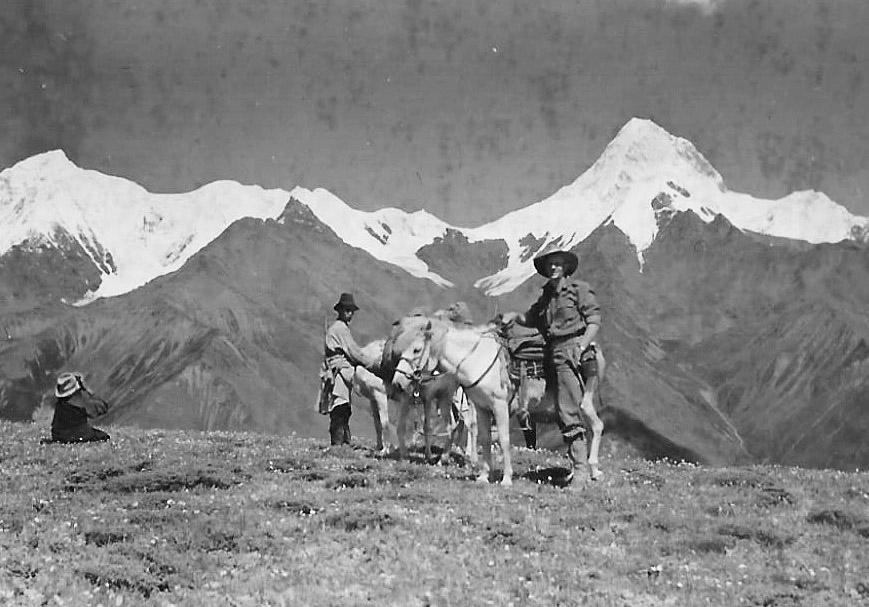

He soon found a means to realise his plan. The American army’s Sino-American Horse Purchasing Bureau was acquiring Tibetan mountain horses and overlanding them to China, where they were desperately needed as remounts. Drawing on information from fellow correspondent James Burke, a Shanghai-born son of American missionaries, he submitted a story about the Bureau in June 1945.

Burke was fluent in Mandarin, was attached to the US Office of War Information, and had previously accompanied one of the Bureau’s Tibetan rotations — all of them skills and experience vital to Johnston’s plan. With his support Johnston was invited to “come along” by the colonel overseeing the Bureau’s next rotation. Improbably, the trip had an Australian angle: the Bureau was exchanging a cargo of slouch hats — much sought after in Tibet — for the all-important horses.

Like Johnston, Burke was entranced by mountainous Tibet, so the pieces fell into place. In mid-July the two men were flown into Ying Kwan Chai, probably the highest airfield in the world at the time but an unpromising starting point for a search for utopia. The place was infested with rats, blowflies and “prowling village mongrels,” the streets “an awful treacly mass of mud and manure.” The pair stayed long enough to acquire riding and pack horses and a local guide, Feng Liu-lu, who spoke Mandarin and Tibetan.

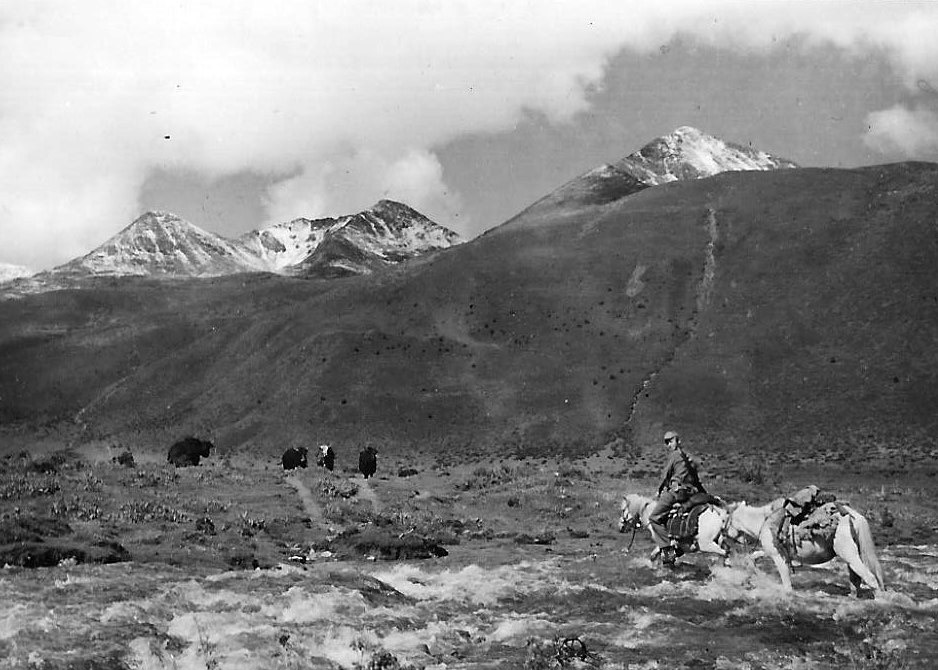

Johnston and Burke encountered a land that was beautiful and enthralling but also demanding and dangerous. They were tested by long days in the saddle, ice-cold streams to be forded, freezing nights, squalls that left them miserably cold and wet, and the danger of vicious Tibetan mastiffs.

The human element was also challenging. Banditry was rife, and while Johnston recorded with interest the Buddhist rituals he observed, he also became contemptuous of avaricious, pestering lamas. Scarce places to sleep were found only in damp, overcrowded inns offering distasteful food amid the odour of rancid butter. Even an apparently idyllic valley turned out to be controlled by farmers who refused them shelter.

But the compensations were enormous. As Johnston and Burke trekked upward, crossing a mountain pass at 18,000 feet, they were overwhelmed by magnificent landscapes of broad, green flower-studded valleys over which loomed pristine glaciers and the mighty, glistening peak of Minya Konka. They were enchanted by “the tinkling of bells and the chuckling laughter of mountain streams.”

James Burke crosses a mountain stream.

The travellers’ mood also improved when they were welcomed by poor nomadic herders summering cattle in the highest valleys. Although Johnston noted that these hosts “smelled prodigiously” he admired their generosity and dignity as they shared their yurts and food with the unexpected passers-by. In this unlikely place, he found a reassuring normality where “so much was as familiar as the everyday scenes on an Australian farm.”

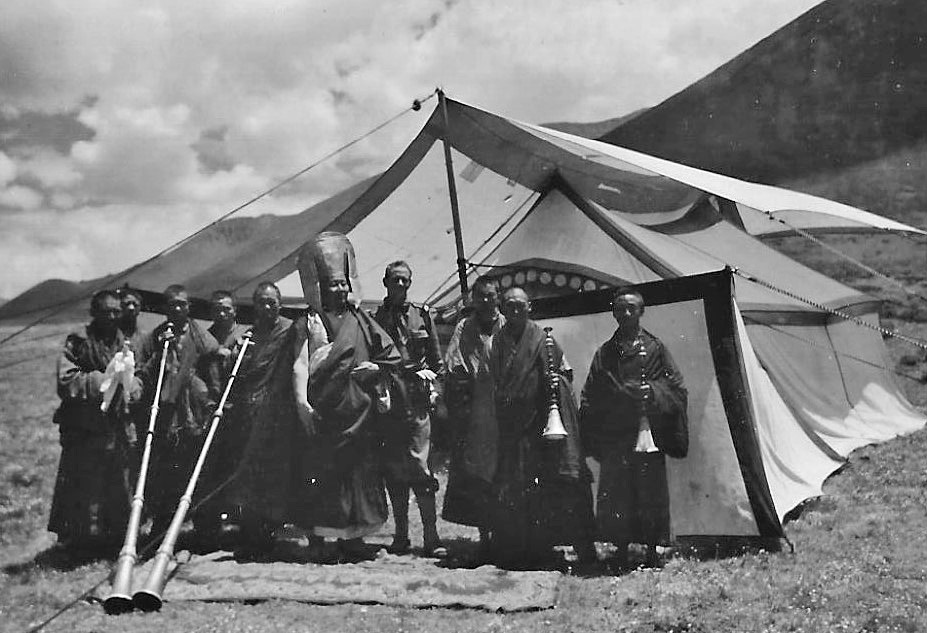

Johnston and Burke had another encouraging encounter when they were invited to meet a Living Buddha (the revered teachers who have reached Tibetan Buddhism’s highest form of enlightenment), Kama Cheuh-ji-sing kai, who had camped nearby with his impressive cavalcade. From having met the Buddha on his previous trip, Burke was aware that his proudest possession was a phonograph on which he had nothing to play but a Noël Coward recording, so he was carrying a “hot jazz” record in case they met again.

After approving this new disc, the Buddha and his guests settled into a lengthy conversation about the basics of reincarnation, diet, prayer and the differences between Buddhism and Christianity. Despite Johnston’s lack of interest in organised religion, he had long been fascinated by other cultures, and he and Burke eagerly maintained a conversation experienced by few Westerners.

Johnston with Kama Cheuh-ji-sing kai (Ninth Gangkar Rinpoché) and lamas.

After nearly a fortnight, a final twelve-hour day of riding took the men and their guide within reach of Konka Gomba, where they faced final challenges from aggressive yaks, the threat of wolves, ever-steeper gradients and unexpectedly thick forests. In surroundings Johnston described as “dreary, dismal and eerie,” the portals of Konka Gomba were suddenly upon them: “Feng stiffened in his saddle, pointed ahead dramatically. ‘There,’ he shouted, exultantly. ‘Konka Gomba!’ Ahead was the real Shangri-la.”

Johnston and Burke’s first impressions of the much-anticipated endpoint of their gruelling yet exhilarating journey were disappointing. The drab, brown, stone buildings and dirty, uninspiring monks were very unlike the gleaming white palace of Johnston’s dreams. The destination was saved only by the drama of its stupendous setting beneath a broad glacier spilling from Minya Konka. Seemingly undaunted, Johnston declared, “That night we slept in Shangri-la.”

After staying several days, however, the travellers despaired of finding Hilton’s utopia. To Johnston the monastery seemed filthy and disorganised and the lamas, while hospitable, covetous and uninspiring. Preparing to leave disenchanted, he and Burke took a desultory final tour of the lamas’ cells.

Johnston and lamas at the Konka Gomba Monastery.

What followed was a meeting Johnston later said he had hesitated to report in case it was “construed as a newspaperman’s invention.” But, he asserted, it “really happened.”

A guide, recognising the visitors’ waning interest, paused before opening a closed door. Then they entered an immaculately clean room containing a solitary figure deep in meditation. In a fairy-tale-like awakening, the figure slowly raised its head, opened its eyes, and removed a hat and spectacles, revealing a beautiful Chinese woman who presented herself as Shen Shu-wen from Peking, also known as Hsueh Shan Chu Shih — “The Snow Mountain’s Resident Scholar.”

Replying to eager questions Shen recounted how she had been a guerrilla fighter resisting the Japanese invasion. Severely wounded, needing to recuperate but unable to return to occupied Peking, she was led by her interest in Buddhism to find refuge in Konka Gomba. Here she had been confined to her room for three years, fasting and meditating under the influence of Minya Konka and the tutelage of Kama Cheuh-ji-sing kai.

Having discussed the progress of her Buddhist learning, including her struggle to understand her reincarnations, Shen enquired about the progress of the European and Asian wars. The men shared the news that Hitler was dead and Germany defeated, but Japan was fighting on.

Johnston and Burke were deeply impressed by this devout warrior-scholar who fused Tibetan spirituality with their own fragile, war-effected condition. And while Shen’s presence was troubling — evidence the war had indeed reached this seemingly untouched place — they saw in her prayerful meditation and meticulous cleanliness someone quite unlike Konka Gombas’s listless lamas.

Reinvigorated by meeting this brave and intelligent woman, Johnston’s faith in Hilton’s utopia was restored. The disappointing lamasery was once more “this fantastic Shangri-La.” After that, “everything was inclined to be anticlimactic.”

The men’s return journey came, however, with its own startling climax. Burke was stricken with a kidney infection and fell into a life-threatening fever. Johnston and Feng kept him sedated and upright in his saddle, but progress was painful and slow. As the desperate trio entered the valley of Ying Kwan Chai they saw a dismantled airfield, and to their dismay, what was a final US flight taxiing for departure. Fate intervened when one of the plane’s engines stalled. With Johnston frantically firing a pistol to gain attention, they were saved from what he believed would have been certain death in the coming winter. (As far as we’re aware, details of Feng’s subsequent life haven’t been recorded.)

From the aircrew Johnston learnt that he was returning to a world that had changed dramatically while he had been imbibing “a thousand years of mysticism.” It was August 14th and the Pacific War was over, with Japan capitulating after the annihilation of two of its major cities.

As Burke recuperated, Johnston flung himself back into his work, submitting rapid-fire articles covering the war’s end. He was rewarded with a privileged invitation to accompany Allied representatives to Japan, where he attended the formal surrender onboard the USS Missouri and visited “the heat-fused nightmare of Hiroshima.” The disparity between visiting the uplands of Minya Konka and the wastelands of the Japanese holocaust would have been wrenching.

Johnston returned to Australia in October 1945 with his Tibetan adventure still front of mind. Within days he published a long article describing his encounter with Kama Cheuh-ji-sing kai, and soon after another featuring the meeting with Shen Shu-wen accompanied by an illustration of Shen greeting her visitors.

Shen Shu-wen as depicted in the Australasian, 10 November 1945.

Johnston’s 1947 war memoir, Journey Through Tomorrow described his search for Shangri-La and again reported the two memorable meetings. There Johnston’s Tibetan interlude might have remained — except that he revived the story a final time, a quarter of a century later.

Before reaching that point, however, Johnston’s public profile continued to grow, though not always in a way he would have welcomed. His return to civilian life became tumultuous when he began the office affair with Clift that ended his first marriage and caused the pair to be dismissed by Melbourne’s Argus. They departed for Sydney, where they co-authored High Valley, a novel that relied heavily on Johnston’s experience in Tibet.

After Johnston and Clift moved to London in 1951, Johnston took an editorial position on Fleet Street and he and Clift co-authored a second novel, The Big Chariot, this time drawing on Johnston’s knowledge of China. In late 1954, driven by mounting literary ambition and romantic yearning, Johnston and Clift moved on again, this time to the Greek islands. When they arrived on Hydra in mid-1955 they were the only foreigners, but others soon followed. In short time they emerged as the guiding spirits of a proto-hippy community attracting participants disillusioned by postwar optimism’s morphing into cold war reality.

Johnston and Clift’s own reality unfolded as a vexing battle with disappointing literary progress, marital problems, poverty and alcohol. It was a welcome relief when in 1960 Johnston again crossed paths with James Burke.

Postwar, Burke had turned to photojournalism and constantly sought opportunities to work in his beloved Himalayas. Success came his way in 1953 when he was the first newsman to interview Tenzing Norgay after he and Edmund Hilary descended from Everest, and in 1959 he covered the Dalai Lama’s arrival in India after fleeing Tibet.

In 1960 Burke was working for LIFE magazine and found himself posted to Athens. From there he saw the opportunity for a photo-essay based on Johnston and Clift’s pivotal role in Hydra’s bohemian enclave. He started by producing more than 1500 photographs depicting the Johnstons surrounded by a young, off-beat, international cohort that notably featured Canadian writer Leonard Cohen and his partner Norwegian Marianne Ihlen.

But Burke’s photos, after initial acceptance, weren’t published at the time and were instead consigned to the LIFE archive. They only began to circulate more than five decades later when, aided by the internet, they were immediately recognised as a tantalising glimpse of significant lives and a potent picturing of the postwar Aegean on the cusp of transformation.

Burke’s Hydra visit may have also induced Johnston to revisit his own war experience in fiction. He was soon at work on The Far Side of the Moon, a novel dealing with a remote Himalayan airfield and Allied crews flying the “hump” route between northern India and China. This was written simultaneously with The Far Road, in which Johnston recounted his traumatising experience among the fields of Kweilin in 1944. In the same period he also completed another novel, I Was the Only War Correspondent, which remains unpublished.

It was, however, My Brother Jack — the concluding sections of which expose war correspondent David Meredith’s guilt-riddled examination of his non-combatant war service — that brought Johnston the longed-for popular and critical success that allowed him to return to Australia. His fortunes were temporarily buoyed but he remained troubled by unresolved personal and health issues. Clift’s suicide in July 1969 added to his woes and focused his preparation for his own demise. He responded by embarking on A Cartload of Clay, the final instalment of his life-spanning trilogy.

In that novel Meredith mirrors Johnston’s real-life battle to come to terms with his wife’s suicide and make sense of his own life before he too dies. In preparing for death Johnston creates a book deeply engaged with pressing question about “life” — the life one has led, the lives one might have led. Johnston (and Meredith) confronts myriad missteps made while playing the “absurd game of going from the cradle to the grave” and the inadequate means individuals have to shape their destiny amid the disarrayed forces of character, opportunity, fate and chance.

Meredith’s contemplation of these matters is compressed into a single day — a day that involves another uphill journey with a religious destination, his local church. But his capacities are depleted by tuberculosis and emphysema, and the short walk requires rest. He finds a bus stop, sits and dozes. His mind wanders restlessly over the contours of the lives of those with whom he has “shared the oars,” and the deaths of those who have preceded him to the grave.

In particular, Meredith returns to the war years and to 1945 and his Tibetan journey with “Jim” Burke. But it is no longer a trek in search of a fabled lamasery or punctuated by meeting a Living Buddha and a cloistered warrior woman. It is now recalled as a time of existential transformation triggered by the staggering landscape. The two men ride “wherever the whim took them [through] long verdant valleys” amid the “Wagnerian drama of tremendous evening blizzards spawned out of the glittering cold womb of the mighty and sacred peak of Minya Konka.” It’s an “exhilarating bizarre experience” by which he and Burke were changed, perhaps for the last time in their lives.

This time the journey is resolved by a more complete account of Burke’s near death and the rescue of the two men in 1945, followed by his actual death in 1964. Meredith recalls learning how his friend slipped and fell while photographing in the Himalayas, his body spiralling into a crevice and beyond retrieval. This was “a precisely right sort of death” for Burke — who had remained driven by his singular passion for the mountains. Meredith, however — reflecting Johnston’s tendency to see purpose and success in others and little in himself — reviews his own postwar progress from Sydney to London to Hydra and back to Sydney, and finds only disappointment, diversion and an unfulfilled “quest for meaning and self-recognition.”

A Cartload of Clay remained unfinished when Johnston died in July 1970 and was published incomplete. It is clear, however, that the Tibetan journey was to be the narrative’s pivot point — the before-and-after, end-of-war moment beyond which the contrasting but linked fates of Meredith and Burke were sealed.

The end of the war was also a watershed for others. Unknown to Johnston, it allowed Kama Cheuh-ji-sing kai and Shen Shu-wen to descend from Minya Konka. Kama Cheuh-ji-sing kai — whose name is now usually rendered as Karma Chokyi Senge and who is widely revered as the ninth Gangkar Rinpoché — toured extensively through China teaching the fundamentals of Tibetan Buddhism. His impact established the religion as an important (and repressed) component of Tibetan cultural survival within China, with Rinpoché as its recognised founder and guiding spirit.

The war’s end also allowed Shen to return to China, where she continued to follow and promote Rinpoché’s teaching. After his death in 1957 she moved to Taiwan and established the influential Dharma centres that made her a critical force in promoting Tibetan Buddhism on the island. She died at ninety-four in 1997 and is now revered as Gongga Laoren.

The details of the crucial teacher–student relationship between Rinpoché and Shen had for decades been impervious to scholars of Tibetan Buddhism. They found no evidence to support Shen’s claims that she spent the war at Konka Gomba as Rinpoche’s disciple. It is only the recent rediscovery of Johnston’s accounts of his Tibetan journey, particularly the reports of his conversations with Burke and Shen, that confirmed she was indeed the legitimate inheritor of Rinpoché’s religious teachings.

Johnston remembered his Tibetan journey for its exhilarating, if temporary, effect on his own wellbeing. It is testimony to Johnston and Burke’s insatiable curiosity about people, their lands and their cultures that Johnston’s words (like Burke’s Hydra photographs) endured, were rediscovered, and were eventually comprehended in a very different context. Nearly eight decades later, Johnston’s story of war-effected lives colliding in an unforgettable location amid the devastating conclusion to a near-global war has found its full significance. •

We are grateful to the family of James Cobb Burke for their assistance and permission to use the above photographs; and to Professor Yunfei Bai, Lingnan University, Hong Kong, for sharing his knowledge of the ninth Gangkar Rinpoché and Gongga Laoren.