Although Australian public opinion since Federation in 1901 has generally been overwhelmingly hostile towards “boat people,” this hasn’t invariably been the case. When small numbers of West Papuan asylum seekers arrived in Queensland in 1969 and 2006, for instance, they didn’t incite the kind of panic that has accompanied more recent arrivals. And when the first five Vietnamese landed in April 1976, they hardly registered outside Darwin. But that would change as arrivals from Vietnam increased, with an unexpected impact on the following year’s federal election.

It was in December 1976, after the arrival of the third boat, that the earliest signs of panic appeared in the major newspapers. Melbourne’s Sun-News Pictorial, for example, warned of a “tide of human flotsam” lapping the shores of northern Australia, and speculated about an invasion of Australia’s far north “by hundreds, thousands and even tens of thousands of Asian refugees.”

But even after another 167 “boat people” arrived in Australia during the first nine months of 1977, they were still only a major topic of conversation in Darwin. And even there, most people seemed unperturbed. In fact, if the local newspaper is any indication, the feat of steering small fishing boats from Southeast Asia to Australia sparked admiration rather than fear. “Eight Brave Sea to Achieve Dream,” read the headline of a front-page article in the Northern Territory News on 26 September. It’s possible that people in Darwin were kindly disposed towards these boat arrivals because earlier that month they had closely followed the exploits of the Can-Tiki, a boat made from beer cans, which a group of local residents sailed from Darwin to Singapore to promote tourism to Australia’s Top End.

But then the pace of unauthorised boat arrivals picked up. After 102 Indochinese arrived in October and two more boatloads reached Darwin in the first half of November, concerns about exotic diseases and doubts about the effectiveness of the authorities’ surveillance of the northern coastline grew louder – particularly after a boat was found to have entered Doctor’s Gully in Darwin under the noses of the Australian military. Even in the southern states, the public discussion intensified.

On 16 November, for the first time, the immigration department didn’t immediately grant thirty-day temporary entry permits to passengers on a newly arrived boat, and initially refused to allow them to disembark. Immigration minister Michael MacKellar announced that his department would now “assess the implications of unauthorised entry as a matter of urgency.”

Three weeks earlier, prime minister Malcolm Fraser had ended the pre-election speculation by announcing that Australians would go to the polls on 10 December. Although Fraser had favoured admitting more refugees from Indochina in the months before the previous election, in 1975, boat arrivals had barely figured in a campaign overshadowed by the death throes of the scandal-ridden Labor government of Gough Whitlam. Fraser’s Coalition had won power because a majority of voters didn’t trust Labor to steer Australia through a time of economic crisis.

Initially, it seemed the 1977 campaign would be no different. It began badly for the government when Fraser was forced to demand the resignation of the Treasurer, Phillip Lynch, who had been implicated in shady land deals in Victoria and criticised for the use of a family trust to minimise his tax obligations. These issues dominated the first half of the campaign, and Fraser later confided that he would not have called an election had he known about Lynch’s troubles. (Lynch was subsequently cleared of any improper conduct.)

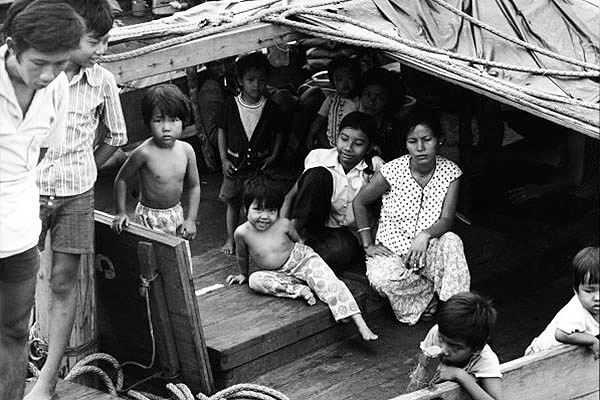

Halfway through the campaign, however, boat arrivals seemed set to play a major role. On 20 and 21 November – less than three weeks before the election, and coinciding with the Coalition’s formal campaign launch – six boats arrived in Darwin with 218 people on board. In one newspaper report, they were dubbed “the second fleet.”

One of them was the VNKG 1062, called Tự Do (“Freedom”) by its owner. It was less than twenty metres long and had thirty-one people, including seven children under the age of ten, on board. Today that boat is in the collection of the Australian National Maritime Museum in Sydney. In 1977, it was owned by a thirty-year-old businessman, Tan Than Lu, who had meticulously planned his escape from Vietnam and had had the boat built specifically for that purpose. Together with family, friends and neighbours, he left Vietnam on 16 August 1977. The Tự Do initially made landfall in Malaysia, from where Tan Than Lu unsuccessfully sought resettlement in the United States. After a month in Malaysia, he decided to push on towards Australia. The boat made another landfall in Java, where the refugees were reprovisioned by Indonesian officials, who then told them to move on. Off Flores, they encountered another refugee boat, which had run aground, and they towed it across the Timor Sea all the way to Darwin.

News of the first two vessels came as MacKellar and Labor’s acting immigration spokesman Tony Mulvihill, a former chair of the Commonwealth Immigration Advisory Council, were discussing refugee issues on ABC Radio’s The Policy Makers. The immigration minister took the opportunity to promise a new committee to assess claims for refugee status. Such a committee had been on the cards since 24 May that year, when MacKellar had announced plans for Australia’s first comprehensive refugee policy.

Mulvihill flagged Labor’s intention to limit the number of refugees Australia would take and criticised the government for accepting boat arrivals indiscriminately. He also claimed that many refugees in Latin America were “under worse political duress” than the people fleeing Indochina.

The next day, NT Labor senator Ted Robertson urged the government to “spread the word” that Vietnamese refugees arriving by boat were unwelcome. The government must “make it clear,” he said, “that Australia is not going to open the floodgates… We will have to try and find a way of showing our sympathy while stopping the flood of what basically are illegal immigrants.” In the NT Legislative Assembly, both sides of politics – including the Country Liberal Party’s majority leader Paul Everingham and Labor’s Jon Isaacs – deplored the unchecked arrival of boats. So did the mayor of Darwin, Ella Stack. “I think some of the last boatload of refugees are pseudo-refugees,” she told ABC Radio’s AM. “They just don’t look like refugees or people who have suffered, or have had the trauma of that long trip.”

Australians in the southern states read uncritical reports of this and other alleged first-hand testimony in their newspapers. In one case, the Australian quoted an unnamed “health department official,” involved in processing boat arrivals in Darwin, who observed that they looked “as though they’ve been on an excursion cruise” and commented that he had “seen people in much worse condition after the Sydney to Hobart yacht race.” At that stage, four or five days after the arrival of the six boats on 20 and 21 November, neither journalists nor the immigration department seemed interested in challenging statements of this kind. The majority of the first media reports suggested that Australians had good reason to be alarmed about the boat arrivals; only the Sydney Morning Herald published an editorial that bucked the trend. “Australia must take all that it can,” the paper argued. “These people deserve our admiration, our compassion and our help.”

The belief that people who weren’t destitute and weren’t visibly suffering could not possibly be refugees also featured prominently in statements made by officials from the Waterside Workers’ Federation, which had called on its members in Darwin to strike in protest against “preferential treatment” for refugees. A resolution passed by the federation’s Darwin branch immediately after the arrival of the six boats referred to the Vietnamese arrivals as “illegal immigrants” and cast aspersions on their “moral fibre” because they supposedly had been able to “finish up at the end of a very long war with gold bars and servants.”

On 24 November, the federation’s president, Curly Nixon, declared that the recent boat arrivals were not refugees because they had “pressed trousers, gold, and in one case three servants.” Nixon also claimed to know why the “boat people” were able to afford all this. “Who makes money out of a civil war?” he asked. “Black marketeers, dope runners, and brothel keepers. You’ve got the lot here. If they said good morning to me, I’d put my pyjamas on and go to bed, that’s how far I trust them.”

The same day, Mulvihill repeated Nixon’s claim that the recent arrivals were wealthy and included brothel owners. Darwin waterside workers proved responsive to such incitements. According to a Times correspondent, some of them hurled insults at “boat people.”

Much of what Nixon and others said was based on little more than hearsay and speculative gossip. An article in the Northern Territory News used a “reliable” (but unnamed) source to suggest that the movement of Indochinese refugees from Thailand to Australia was part of a racket. In the Legislative Assembly, Labor’s Isaacs said that “there is concern that the refugees are part of a well-orchestrated organisation” because some of the boats had new engines and modern navigation instruments. (It was later established that only one of the boats had a new engine, taken from an American tractor owned by one of the refugees.)

Fraser’s government was unprepared for the strength of the reaction. Detailed speaker’s notes compiled earlier that month by the Liberal Party’s federal secretariat referred briefly to the government’s “far-reaching and humanitarian” refugee policy, but otherwise didn’t mention either refugees or unauthorised arrivals. The government nevertheless presented a united front. In the first panicky week after the arrival of the Tự Do and the other five boats, the senior Liberal politicians who commented publicly on the issue echoed the concerns voiced by unions, Labor, and political leaders in the Northern Territory. Fraser and his colleagues appeared intent on placating anxiety about boat arrivals and determined not to let Labor exploit the issue.

On 22 November, immigration minister MacKellar responded to the resolution passed the previous day by the Darwin wharfies. While he stressed “Australia’s obligation to deal in the most sympathetic terms with people who, to the best of the ability to determine the facts, were genuine refugees,” he seemed anxious not to appear to be too critical of the waterside workers’ outlandish claims. He “well understood that there could be differing views held about the movement of refugees into Australia by these means,” MacKellar said, and “[t]here was no question that a rising flow of small boat migration would require a continuing review and tightening of the surveillance procedures.”

MacKellar’s half-hearted defence of the admission of “boat people” who were found to be refugees, coupled with his professed empathy with Australians who voiced strong and evidently irrational objections to unauthorised arrivals, anticipated a position taken by Labor prime minister Julia Gillard in the 2010 election campaign. By repeatedly assuring Australians hostile to asylum seekers that she fully understood their concerns she legitimised objections similar to those made in 1977 by unionists and local leaders in Darwin.

Also on 22 November, in a speech to the NSW branch of the Institute for International Affairs, MacKellar warned that “no country can afford the impression that any group of people who arrive on its shores will be allowed to enter and remain.” He painted a dire picture of the consequences of an unchecked arrival of refugee boats. “We have to combine humanity and compassion with prudent control of unauthorised entry, or be prepared to tear up the Migration Act and its basic policies,” he said.

Foreign minister Andrew Peacock said that Australia could not “continue to indefinitely accept Asian refugees arriving unannounced by sea” and should not be regarded as “a dumping ground.” Both Fraser – who had reportedly been warned by his advisers that the issue could be a campaign “sleeper” – and MacKellar flagged that asylum seekers arriving by boat would not necessarily be resettled in Australia, and could indeed be sent back. “Limit on Refugees Says PM,” read a front-page headline in the Brisbane Courier-Mail.

The government was rattled partly because it had also been told that more boats were on their way. On 23 November, the immigration department informed its minister that at least twelve boats were already en route to Australia, another forty boats were feared to be about to set out from Thailand, and some 2000 people wanted to head for Australia from Malaysia.

The increase in boat arrivals in Australia was partly due to a hardening of the position of Southeast Asian nations. In Thailand, which then housed the largest number of Indochinese refugees, refugees were being pushed back across the border, wherever possible, under a policy introduced on 15 November. Only when that proved impossible would claims be investigated by district-level committees. According to Australia’s ambassador in Bangkok, who toured Northern Thailand a month later, those found to be refugees were housed in camps that were not supervised by the UNHCR; the others were “prosecuted for illegal entry and then sent to one of the three new camps on a ‘temporary’ basis pending return to their country of origin whenever that becomes possible.”

MacKellar and his department recognised that in order to get an anxious Australian public off the government’s back, it was important to stop, or at least slow, the arrival of boats, and that would require a substantial increase in Australia’s intake of Indochinese refugees from camps in Southeast Asia. Up to that point, the intake had been comparatively low (with a total of 2,958 Indochinese refugee arrivals, including those who had come by boat, in 1977).

On 23 November, the Ministers for Immigration and Health, MacKellar and Ralph Hunt, announced that a team of immigration officials would be dispatched immediately to Malaysia and Singapore. Just two days later, the Department of Foreign Affairs was able to tell its minister that the strategy seemed to be working: according to information provided by representatives of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, three boatloads of refugees had decided to postpone their departure from Malaysia following the announcement of an increase in Australia’s resettlement program.

MacKellar and Hunt’s statement didn’t mention how many refugees Australia would be prepared to resettle. Although a senior immigration bureaucrat told a meeting of immigration and foreign affairs officials that Australia ought to be resettling 10,000 Indochinese in the 1977–78 financial year, the department had been instructed to select just 1000 refugees from Malaysia and 500 from Indonesia.

The two ministers also announced that “urgent consideration was being given to surveillance requirements essential to safeguard Australia against unauthorised entry,” but they didn’t say how such surveillance could have an impact on unauthorised entry. Surveillance would simply provide the government with more advance notice and prevent a repeat of the embarrassment caused when the authorities became aware of refugee boats only after they had entered Darwin Harbour.

In fact, none of those who demanded that “boat people” be stopped from entering Australia made any practical suggestions as to what a “stop the boats” policy could look like. “Would not some of them be likely to sink on the return voyage?” the Sydney Morning Herald asked in an editorial in early December that was scathing of the policy promoted by Mulvihill and others. “Would any government risk the hostile public reaction which would be bound to follow?”

Meanwhile, sections of the media and senior Labor politicians continued to throw petrol on the flames. “Illegal immigrants masquerading as refugees should be returned to their countries of origin – and billed, where possible, for the cost of their passage home,” the Courier-Mail demanded in a 24 November editorial. Tony Mulvihill called on the government to “make an example” of some of the unauthorised arrivals: “We have to turn a few of them around, and send them back to Southeast Asia under naval escort.” Although he had a long record of championing the rights of migrants, Mulvihill knew that recently arrived migrants were concerned about the potential impact of the boats on Australia’s family reunion program, and he was aware that their representatives were likely to oppose admitting people who had not applied through the usual channels.

The next day, the Australian suggested that “troublesome political arrivals” should be sent “straight back” and that “criminal bully boys (it is said that some recent refugees slit throats to get the riches they are arriving with) should be sent packing, too.” Labor leader Gough Whitlam claimed that Australia needed to do more to police its northern borders if it wanted to prevent unauthorised immigration, drug importation and the spread of infectious diseases, subtly associating asylum seekers with illicit substances and dangerous viruses. He also doubted the legitimacy of refugee claims made by Vietnamese, suggesting that it was “not credible, two-and-a-half years after the end of the Vietnam war, that these refugees should suddenly be coming to Australia.”

Three days later, Whitlam conceded that “genuine refugees” should be accepted but warned the government not to put boat arrivals ahead of applicants “in the queue” who were sponsored by their relatives. Labor politicians portrayed themselves as speaking on behalf of people who would be disadvantaged by Australia’s acceptance of boat arrivals. The imaginary queue was soon to become one of the most powerful images in the anti–“boat people” discourse; it served to distinguish “good” from “bad” prospective immigrants.

For almost a week, the government said nothing to contradict Labor. Nor did it challenge journalists reporting the hostile views of unnamed government officials, including “authorities in Darwin” and an officer in Bangkok who had used the term “armada” to describe the number of boats on their way to Australia. “Reports say at least sixty boats are on the way to Darwin,” the Sun-Herald claimed, but it did not reveal who had written these reports.

Then, on the weekend of 26–27 November, the tenor of the public debate began to shift. MacKellar denied that an “armada” was on its way, and pointed out that the combined value of the possessions of the latest 220 Vietnamese boat arrivals was estimated at just $10,000. Church leaders and fifty-seven Sydney academics wrote an open letter to the government in which they invoked Australia’s obligations “as a stable and relatively prosperous nation,” highlighted the responsibility of individual Australians “to receive refugees and other migrants into the community,” and called for a substantial increase of the country’s refugee intake. The leader of the recently established Australian Democrats, former Liberal MP Don Chipp, became the first prominent politician to speak up against the idea that the boats could be turned back.

Some newspaper editors now remembered that journalists were obliged to assess claims critically before publishing them. An editorial in the Hobart Mercury on 28 November ridiculed suggestions that the Vietnamese had somehow been able to bring substantial quantities of gold to Australia without attracting the attention of the customs department. Some Labor figures, said the paper, were “seizing on the refugee question with the same sort of enthusiasm formerly reserved for extremists propounding the danger of the Yellow Peril to our North.” (The editorial didn’t mention that earlier Labor leaders had been prominent among those extremists too.) Both the Mercury and the Sydney Morning Herald warned against making the refugee problem into an election issue. The Herald also questioned claims of a “flood” or “horde” of Vietnamese descending on Australia: “How many hundreds of refugees are there in a flood or a horde?”

While the government was scrambling to deal with the influx of refugees who had arrived on 20 and 21 November, it was also monitoring the movements of a vessel bound to pose bigger problems than any of the boats that had arrived thus far. The Song Be 12 was a refrigerated trawler that had been nationalised after April 1975 by the Vietnamese government. To prevent its crew from using it to escape Vietnam, armed soldiers had been placed on board. The ship’s crew had seized control of the ship after overpowering and imprisoning the guards, however, and set course for Australia.

The Song Be 12 carried 181 people – the largest number arriving in a single boat that year – including three soldiers who initially insisted on being repatriated. As much as it could, using sketchy intelligence from local sources in Indonesia and from the US State Department, the Australian government monitored the progress of the ship through the Indonesian archipelago. On 17 November, the Song Be 12 was reported anchored at Surabaya; local church groups were said to be providing food and medicine to its passengers and crew. The ship left the Indonesian port on 22 November, and a week later HMAS Ardent escorted itinto Darwin Harbour.

The Song Be 12’s arrival added another argument to the repertoire of those anxious about the arrival of “boat people”: not only were they too well-fed and too wealthy to qualify as refugees, they were also no less ruthless than the regime whose clutches they supposedly escaped. The Australian government was now under pressure from two sides: domestically from a Labor Party trying to capitalise on fears about the unchecked invasion of “boat people” and from hostile journalists purporting to represent public opinion, and externally from the government in Hanoi, which claimed that Australia was harbouring pirates.

At last, the Fraser government went on the offensive. At a joint press conference in Adelaide on the day the Song Be 12 arrived, Peacock and MacKellar appealed to their fellow politicians “not to subordinate the issues [raised by the arrival of Vietnamese asylum seekers] to electoral considerations, not to exaggerate the dimensions of the problem, not to attempt to exploit the assumed fears of sections of the Australian public, and not to forget the human tragedy represented by these few small boats.” Their statement suggested that the government was concerned about how the parochial Australian debate would be perceived in Southeast Asia and intended to take on the panic-mongers. Referring to Mulvihill’s earlier statement, the two ministers vowed that their government would not “make examples” of the refugees “by indiscriminately turning some of them back” and would not “risk taking action against genuine refugees just to get a message across.” Doing so, they said, “would be an utterly inhuman course of action.”

Why did the government change tack? From the perspective of 2014, it is tempting to believe that Fraser was concerned that the fear of “boat people,” if condoned by his government, would get out of control – that the genie of xenophobia, once out of its bottle, could not be put back in. But Fraser could not have known about what would happen in 2001, when the nation seemed to be gripped by a collective paranoia that was stoked by the government of John Howard and largely unchallenged by the Kim Beazley–led Labor opposition, or in 2013, when a desperate Labor prime minister signed a deal with his Papua New Guinean counterpart for the processing and resettlement of asylum seekers who had sought Australia’s protection.

By 1977, the argument Fraser had used two years earlier in favour of admitting Vietnamese refugees – that Australia had the moral duty to help its former allies – had lost much of its traction. Politicians and commentators who defended the indiscriminate admission of “boat people” certainly invoked the need to be compassionate, but given that the majority of Australians had never been swayed by this argument it’s doubtful that Fraser would have risked a voter backlash in order to be able to claim the high moral ground.

Following MacKellar and Peacock’s statement, Father Jeff Foale of the Indo-China Refugee Association, the key advocacy group that had been lobbying the government to admit more Indochinese refugees, heaped praise on the immigration minister. “Australia is emerging as a country of compassion and good sense,” he said. “The Minister for Immigration and Ethnic Affairs stands as something of a hero, being the only politician who did not lose his cool under fire.” But the archival evidence suggests that MacKellar couldn’t claim the credit for the press conference on 29 November. The fact that it was not Fraser, nor MacKellar by himself, who announced that the government would maintain its approach towards “boat people” indicates that Peacock and his department were the driving force behind the government’s stance.

It was also Peacock who rejected suggestions that the government ought to be guided by public opinion on the issue. On 1 December, in response to a radio interviewer’s suggestion that Darwin residents had expressed concerns about the numbers of refugees arriving by boat, he said, “Indeed they have, but they are not the government.” And when asked, “You have no suggestions at all that we should be stopping these boats from coming in?” his response was unequivocal: “None whatsoever.”

Peacock and MacKellar’s statement suggests that the government decided to take on the panic mongers out of a concern about how the Australian debate was being perceived in Southeast Asia. “The problem is a regional problem and the validity of Australia’s credentials as a good neighbour will depend largely on a willingness to meet our regional obligations by bearing part of the burden,” the ministers’ statement read. The potential diplomatic fallout of a policy of the kind favoured by senior Labor politicians was also noted by other informed observers at the time. The Sydney Morning Herald’s Southeast Asia correspondent, Michael Richardson, for example, whose reports about the refugee crisis in Southeast Asia had tried to convey the complexity of the problem to his readers, wrote on 29 November that the decision to turn back refugee boats “would raise a chorus of protests from neighbours whose friendship Australia wants to retain.”

In fact, news of the response of the Australian public to boat arrivals in the last week of November had already generated unfavourable headlines in the region. And on 25 November, Thailand’s ambassador to Australia, Wichet Suthayakhom, had issued a statement in which he defended Thailand’s response to Indochinese refugees while deploring the Labor Party’s stance. He was particularly incensed by Mulvihill’s suggestion that Australia cut its foreign aid to Thailand to discipline the Thai government for refusing to accommodate more Indochinese refugees.

The Fraser government also had reason to be concerned about the damage being done to Australia’s reputation as a defender of human rights and advocate of humanitarian solutions. On 29 November, the deputy high commissioner for refugees, Charles Mace, and the UNHCR’s acting director of assistance, Franz-Josef Homann-Herimberg, called on Australia’s ambassador in Geneva to express the organisation’s concern that Australia might be willing to turn back Vietnamese boats. They argued that such a course of action would be irresponsible on two counts. For humanitarian reasons, the boat arrivals could neither be sent back “nor sent on elsewhere,” even if they were not, strictly speaking, refugees. And turning boats back would weaken the position of the UNHCR, which was appealing to Thailand, Malaysia and the Philippines to allow “boat people” to land.

Some of Australia’s allies were also concerned about the public hostility to the landings in Darwin, and about the mixed messages sent out by the Fraser government. In December, the Australian embassy in Washington, for example, warned that Australia risked “being singled out in Congress, and elsewhere, as a country which is lagging in humanitarian concern for Asian refugees.”

Judging by the indignation it engendered, the negative publicity in London and Washington that was, or threatened to be, generated by the government’s seeming capitulation to vox populi troubled Fraser and his ministers. One scathing newspaper column in particular, published on 30 November in London, caught their attention. It appeared in the Times, whose viewsAustralian governments tended to take more seriously than those of any other media outlet. And to make matters worse, its author was Britain’s most famous columnist at the time, Bernard Levin. Although his thoughts were published after MacKellar and Peacock’s joint press conference, it was obviously written before the Australian government had clarified that it would not turn back Vietnamese refugee boats; thus Levin’s criticism was directed at what appeared to be the government’s pandering to popular opinion.

Levin didn’t mince his words. Fraser’s warning to Indochinese refugees was an unparalleled “swinery” designed to placate the xenophobic vote. And while Australia was not alone in telling Indochinese “boat people” that they were not welcome, it had no excuse – unlike its poor Southeast Asian neighbours – because it did not lack the capacity to accommodate refugees. “What is more,” Levin wrote, “there would still be no excuse for Australia if the Vietnamese refugees were counted in hundreds of thousands, instead of in ones and tens.”

The impact of Levin’s article can be gauged by the fact that two of Fraser’s former colleagues rushed to his defence on the letters pages. Gordon Freeth, a former foreign minister and in 1977 Australia’s high commissioner in London, and Malcolm Mackay, a former navy minister, both tried to rebut Levin’s arguments: the former by drawing on the statement issued by MacKellar and Peacock on 29 November, and the latter by claiming that Australia was a “country with enormous problems… torn by fire, drought and exotic cattle disease, as well as the man-made problems of industrial upheavals.” No doubt Mackay’s defence would have confirmed Levin’s view that Australia was “apparently determined to retain, and indeed strengthen, her reputation as the armpit of the Southern Hemisphere.”

When Peacock and MacKellar jointly committed the government to hold the line, they had reason to be confident that the Coalition would be returned with a majority at the 10 December elections. The government may have thought that it could afford to let Labor play to Australians’ fears of an Asian invasion while hoping that Whitlam and his colleagues would temper their rhetoric after the elections. It was concerned about the mood in Darwin, however, where Stack and Everingham continued to paint alarmist pictures and demand that the government stop the boats from landing. MacKellar eventually dispatched a senior immigration official, Derek Volker, to talk to local leaders in Darwin. The report of this visit must have reinforced the government’s view that the situation could not be allowed to spiral any further out of control. Darwin people were genuinely concerned about an invasion from Indochina and Southeast Asia, Volker found. The local response to “boat people” was uninformed, even at the highest level, and tended to be exacerbated by the sense that Darwin was isolated from and neglected by the rest of Australia.

Emboldened by the government’s somewhat belated shift, senior Labor figures continued to try to exploit the arrivals for electoral gain. Bill Hayden, who was touted as the next Labor leader (and who would indeed succeed Whitlam within two weeks of the election), told the Perth Press Club that sailing into Darwin was as easy as crossing Sydney Harbour on a Manly ferry. But of all senior Labor politicians, it was Labor Party president and trade union leader Bob Hawke who was most openly opposed to the admission of the Indochinese. Campaigning in Hobart on 28 November he demanded that they should be subject to normal immigration requirements and that those who failed to meet such requirements ought to be deported. On 1 December he suggested that Australia should only accept refugees selected offshore.

Hawke also anticipated two lines of argument made famous by John Howard during the Tampa crisis in 2001. He said that Australians were renowned for their compassion, and would willingly accommodate refugees “who have gone through our formal process of screening and… meet our requirements.” Unauthorised refugee arrivals, however, did not have “a total monopoly on our compassion.” In Hawke’s view, Australia had the right as a sovereign nation “to determine how it will exercise its compassion and how it will increase its population.” Hawke’s attempts to make the boat arrivals into a key election issue were half-hearted, however, and after a few days in which “boat people” dominated the front pages of newspapers around the country, the issue lost traction.

Three days out from the election, there was one last attempt to exploit Australians’ fear of uncontrolled boat arrivals. This time it was not made by a senior opposition figure, but by a government minister. As if to underline the fact that not everybody in the government agreed with the line adopted by Peacock, MacKellar and Fraser after 29 November, transport minister Peter Nixon, a National Country Party MP, announced that henceforth “boat people” would only be allowed to land in Australia if they had been cleared by Australian immigration officials in refugee camps in Thailand or Malaysia. “If they leave the camps without going through Australian immigration checks, then their boats will be sent back to where they came from,” he was reported to have said in Darwin. The next day, MacKellar flatly denied that the government would turn back boats, and Nixon’s office scrambled to retract his statement. By then, however, it had been widely reported, both in Australia and overseas, and elicited another concerned response from the UNHCR in Geneva.

Political scientists agree that Nixon’s intervention didn’t influence the election outcome. The fact that there were no further boats in the last week before the polls might have helped take the issue off voters’ minds. Yet it had been an otherwise dull campaign, and in the light of subsequent federal election campaigns – including those of 2001, 2010 and 2013 – it is striking that the debate died almost as soon as the government defended its policy.

After all, Labor could have used the refugee issue more vigorously to distinguish itself clearly from the government and to seek electoral gain by appealing to xenophobic sentiments and a latent fear of invasion. Labor was clearly hesitant to do so – perhaps because most of its leaders knew the dangers of fear-mongering, and because both sides of politics had traditionally taken a bipartisan approach to immigration matters and they were hesitant to abandon that.

On 10 December, Fraser’s Coalition government lost two seats to Labor in Queensland but won a comfortable majority overall. In the House of Representatives its primary vote dropped by almost 5 per cent, but Labor’s primary vote dropped too because Chipp’s Australian Democrats, contesting their first federal election, attracted over 9 per cent of the primary vote. The Coalition’s election win, the approaching summer silly season and the fact that there was a lull in the arrival of refugee boats defused the issue that had excited politicians and commentators in late November and early December.

The campaign was the first in Australian history in which one of the major parties appealed to the public’s unease about unauthorised boat arrivals. It was the moment when much of the rhetoric to which Australians would become accustomed during the Howard, Rudd/ Gillard and Abbott years made its first appearance.

During the Tampa election of 2001, and then again in 2010 and 2013, Labor assumed that it would suffer disastrously if it didn’t try to match the anti–asylum seeker rhetoric of the Liberals and Nationals. It worried that a considered and principled stance, like the approach adopted by Don Chipp in 1977, and eventually taken by Fraser, Peacock and MacKellar, would severely damage its standing at the polls. It would be fascinating to see one of the major political parties test this orthodoxy. The experience of 1977 suggests that it might not be as risky as Labor leaders from Kim Beazley to Kevin Rudd have assumed. •