Anyone visiting the rooms in old Parliament House where Gough Whitlam first worked as prime minister will be immediately struck by their size – not by how large they were, but how small. They were on the Senate side of the building. The furnishings were primitive. Staff worked three or four to a room and the space was cluttered for months on end with files and packing cases.

Admittedly it was a temporary arrangement, intended for Whitlam’s use while the regular prime ministerial suite was undergoing renovation. But even the so-called permanent quarters, which Whitlam occupied several months later, were modest by today’s standards. Elizabeth Reid, who was to join Whitlam as his adviser on women’s matters, complained about the narrow corridors. “Half the business in Parliament House is conducted in the corridors,” Liz used to say, “and they aren’t wide enough for a decent committee meeting.”

Whitlam began with a core staff of around twelve (though this number was later to grow). A prime minister today – even a premier – works with a staff of thirty or forty. Naturally we liked to think that we made up in talent and enthusiasm what we lacked in numbers. Michael Delaney, who joined Whitlam’s office as a private secretary and later became a senior adviser, had a list of duties that covered, in his own words, “all public service matters, all dealings with the Public Service Board, all liaison with the Prime Minister’s Department, management of the caucus meeting agenda and papers… and everything else that was dogsbody stuff done by a useful youth.” In addition, Delaney had to accompany the prime minister on his travel and look after constituency correspondence, planning and research. It was a lot for one man.

But that was how government worked in those days. While a prime minister today has a policy adviser for every major area of government activity, Whitlam had no such team. He saw no need for one. Policy advice – according to all constitutional theory and Westminster precedent – was the preserve of the public service. Tension between Whitlam’s staff and the entrenched bureaucracy was the defining feature of the Whitlam government’s operations. The public service was run by an aristocratic cabal of venerable men who lunched regularly at the Commonwealth Club and regarded the new Labor government with suspicion. Steeped in old-school values, they had no time for ministerial advisers.

I had an early taste of the attitudes of the Canberra bureaucracy on the day I joined Whitlam’s staff, in January 1973, as his press secretary. I was asked to report in the first instance to Sir John Bunting, permanent head of the Prime Minister’s Department. After greeting me with some affability, Sir John insisted I take an oath of allegiance to the Queen, which he proceeded to administer himself, using a Bible produced from a drawer in his desk and presumably kept for the purpose. When I inquired why an oath was necessary, Sir John explained that it was normal procedure. When I pointed out that I was not joining the public service but working as a temporary member of the PM’s staff, I was told that the same rule applied. Sir John managed to convey that such rules were even more necessary for former journalists and other ministerial hangers-on than they were for career officers, whose loyalty might be taken for granted.

Whitlam was surprised when I told him I had sworn an oath. He added something to the effect that any oath of allegiance should more properly be sworn to him rather than Her Majesty. It was a joke, of course, but symptomatic of a certain unease within his office.

On the Sunday morning after his election win in December 1972, Whitlam flew to Canberra and returned for the last time to the opposition leader’s rooms in Parliament House. It was from here that he organised his government’s transfer to power. After a couple of hours of briefings from the public service heads he called in the four senior staff from his opposition days to meet the mandarins – Jim Spigelman, who was to be his senior adviser until 1974 and later his principal private secretary; Eric Walsh, the brilliant young Sydney Daily Mirror journalist who would handle the media; Dick Hall, one of his closest lieutenants in opposition; and Graham Freudenberg, his speechwriter. Freudenberg has recalled that after the appropriate introductions, Whitlam said, “I take full and personal responsibility for these men. I vouch for them and they are not to be subject to security clearances. These men are not to be harassed by ASIO.” Not one of the senior mandarins demurred. It is quite likely, I think, that ASIO clearances for “these men” had already been sought and obtained, but we were not to know. I often wondered later if there was a suspected connection between me and the notorious leaker Mr Williams, who regularly fed Treasury documents to the opposition.

For months after the change of government, the Whitlam office felt fragmented and uncertain. For Freudenberg, the very fact that Whitlam was housed in temporary accommodation during those early months stamped the entire government with a sense of impermanence. But it must be said that Whitlam found the arrangement to his liking. With the help of his security detail, he could escape from the building through a door near the rose garden on the Senate side and avoid reporters. It was a while before the press tumbled to the ruse.

The staff were constantly hampered by restrictions on space and mobility. Freudenberg was not classified as a ministerial staff member because there was no official position of speechwriter under public service regulations. At Whitlam’s insistence, a position was found for him in the Prime Minister’s Department. This meant that he was based in West Block, some hundreds of metres from the action in Parliament House, and effectively cut off from the day-to-day workings of the office. The rest of us worked in cramped conditions with limited equipment and facilities.

There were, of course, no computers. Nor, at first, were there photocopiers or even fax machines (though such equipment was in use in the private sector). I remember when the first “facsimile transmitter” was installed in Whitlam’s office in 1975 and none of us knew how to work it. Even electric typewriters, familiar in the outside world, were unknown to us. Denise Darlow, who worked for Whitlam in Sydney and joined him as his personal secretary in January 1975, remembers how everything had to be typed on manual machines. “With five sheets of carbon paper needed for a press release,” she recalls, “I had to hit the keys so hard that the typewriter would fall off my desk when I got up speed.” Freudenberg would come in from West Block at night and dictate a speech to Carol Summerhayes until well into the small hours. Fortunately the office was well-equipped with ashtrays and fridges.

Ministerial staff (such as they were) were drawn mainly from fairly junior ranks of the public service and poorly paid. Every minister was entitled to a Class 6 officer (a little above the lowest clerical grade) and two stenographic assistants, usually female. Whitlam had a bigger establishment, but little choice in the selection of his team. Peter Wilenski, the brilliant young foreign affairs officer who became his first principal private secretary in government (succeeding Race Mathews, who resigned to contest a federal seat), was seconded from within the bureaucracy. He and Whitlam made a first-rate team, but Whitlam was later to insist, against strong bureaucratic opposition, that ministerial staff be chosen by ministers themselves rather than their departments.

In Wilenski, Whitlam was fortunate in having someone who knew how the public service worked and how permanent heads could be handled. He was an invaluable ally in dealing with hostile public service heads who resisted any role for prime ministerial staff. The underlying tensions between the office and the public service establishment were one factor that persuaded Whitlam to set up a commission of inquiry into the public service under the chairmanship of Dr H.C. “Nugget” Coombs. Wilenski was seconded to the commission as its special adviser. (The Hawke government later appointed him chair of the Public Service Board.) Before Whitlam took office, Wilenski had devised a new departmental structure to facilitate the transfer of power and reflect the policies of the new government. Its centrepiece was a machinery of government committee, consisting of the government leaders in both houses, senior public service heads and Wilenski and Spigelman from Whitlam’s office. “Its real importance,” Freudenberg was to write later in A Certain Grandeur, “was that it enabled the politicians, inexperienced as they were in administration, to establish an immediate ascendancy over the public servants.”

One of the first tests of the new relationship was precipitated by US president Richard Nixon’s decision in December 1972 to order heavy bombing raids on Hanoi. It was also an early test of Whitlam’s relations with the media, who were puzzled by Whitlam’s reluctance to condemn the bombings publicly. The Christmas bombings, carried out by hundreds of B-52s and smaller airforce and navy planes, were of a scale and intensity unprecedented in the Vietnam war. A number of Whitlam’s staff, notably Wilenski, Hall and Gordon Bilney, the foreign affairs departmental liaison officer in the prime minister’s office, urged Whitlam to send a letter of protest to Nixon. He agreed. But who would write it? As one of the so-called wordsmiths in the office, I was eager to draft something myself, and prepared a version rich in strident denunciation and outrage. Whitlam accepted a draft prepared by Sir Keith Waller, permanent head of the Department of Foreign Affairs. Its tone, as Freudenberg later put it, was circumspect and courteous, but did little to ameliorate the furious reaction in Washington.

If the bureaucracy saw a diminished role for themselves in policy formulation, there was a good reason. The Whitlam government’s policies had already been formulated in detail by Whitlam himself. He brought with him comprehensive policies on a range of issues – healthcare, urban development, foreign policy, the ownership of natural resources – where most of the work had already been done. No prime minister ever came to office with a clearer, more specific vision of what he wanted to achieve. This was partly a legacy of the Fabian approach to policy formulation that Whitlam had adopted since the day he was elected to parliament in 1952 – rational, incremental reform carried out within the parliamentary system. The leading Fabian on his personal staff, Mathews, became his principal private secretary in August 1967 and together they set about developing the policy platform that Whitlam would bring to government in 1972.

Whitlam’s education policies, for example – the “needs basis” for school funding, the establishment of a Schools Commission – owed much to research undertaken by Mathews in consultation with David Bennett, a leading educational reformer in Victoria. Bennett and Whitlam had much in common. In a monograph on Bennett, Mathews wrote that “he had much of the spectacular irascibility which at times made Gough close to insufferable, but… the same ability to bring out in others the excellence which he expected of himself.” Loyal as he was to those around him, Whitlam never saw his staff as exempt from discipline and never allowed them to shelter behind the leader’s authority. Gordon Bilney has put it well: “Today no staff member can be taxed with responsibility for any decision if the minister decides, as he invariably does, to stand behind him.”

Whitlam took a different view. His ideas about ministerial responsibility and the role of the public servant were very much influenced by those of his father, a former crown solicitor for the Commonwealth government. His son respected public servants for their professionalism and integrity, but nothing enraged him more than a show of truculence (a favourite word) or obstruction. It was the same with his staff. “It was always very clear,” says Bilney, “that if I transgressed I could look forward to having my head on the block.”

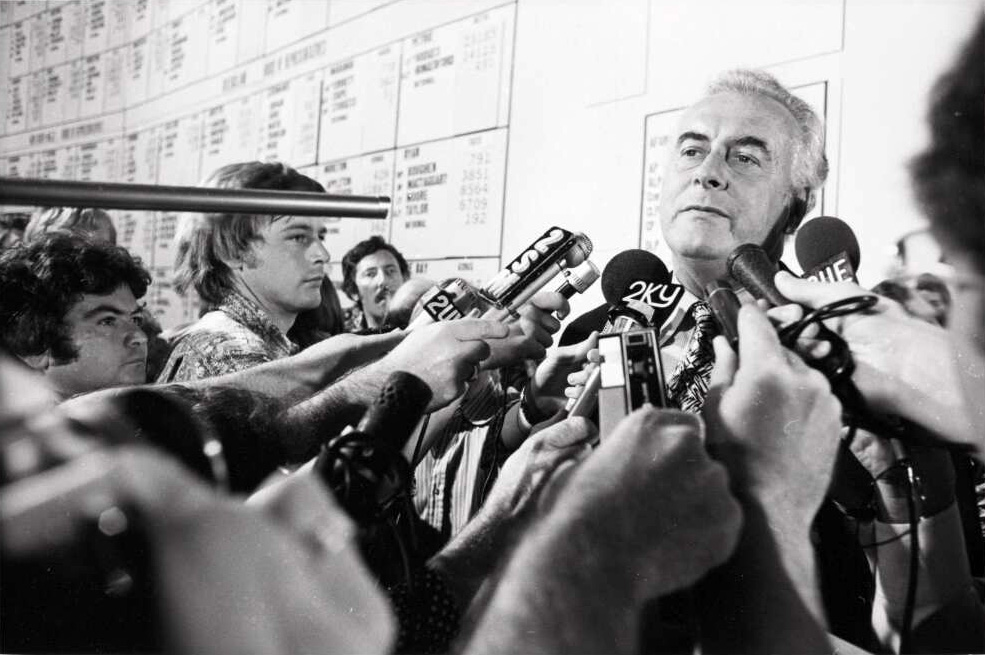

The bigger problem for Whitlam was getting his message across. It was the era before talk-back radio, before spin and twenty-four-hour media management, and Whitlam had the same mild intellectual disdain for the media that Robert Menzies had shown in his day. Media liaison was left to Walsh, who had worked with the Labor national secretary, Mick Young, on Whitlam’s campaign. After every cabinet meeting, Whitlam would tell Walsh what decisions were to be announced and a press release would be drafted. More importantly, Walsh persuaded Whitlam to hold regular weekly press conferences – an initiative that did much to build goodwill with the Canberra press gallery, whose opportunities to question John Gorton and William McMahon had become more and more infrequent and unpredictable. While Whitlam had cordial personal relations with most of the senior gallery figures – experienced hands such as Ian Fitchett, of the Melbourne Age and later the Sydney Morning Herald, Brian Johns of the Herald, Laurie Oakes of the Melbourne Sun, Allan Barnes of the Age, Alan Ramsey of the Australian and such maverick spirits as Mungo MacCallum. He rarely played favourites and individual briefings were rare.

It helped, of course, that many of the younger breed of journalists were sympathetic to the new government. They also liked Whitlam’s support for freedom of information, an idea he largely pioneered in Australia. “Open government” became a Whitlam catchcry. Today, with so many scoops and inside stories made possible by FOI applications, it’s worth remembering that the best journalists in Whitlam’s day made do with their professional skills. Oakes, Barnes and Alan Reid (the Bulletin) broke stories the hard way, exploiting a network of contacts with inside information. It didn’t always help Whitlam, of course. Endless stories about the loans affair, the Iraqi money scandal and caucus dissent were kept alive by the skills of the press gallery. But it’s only fair to remember that in its early days the Whitlam government enjoyed a remarkably long honeymoon with the mainstream press. The Sydney Morning Herald ran a daily page-one summary of the government’s accomplishments, for example:

DAY 15

Introduced new ministry

Announced recognition of East Germany

Began study of ways to reduce unemployment in NSW

Announced plan for Interim Hospitals Commission

Supported four weeks’ leave for public servants

Whitlam’s press conferences were rather formal affairs. The proceedings were transcribed and circulated by Carol Summerhayes because few gallery journalists could take shorthand notes and the use of miniature recording devices was unheard of. Whitlam enjoyed these occasions. If Gorton had been the first prime minister of the television age – and Howard, years later, the first of the age of talkback radio – Whitlam was the first to exploit the full potential of television, projecting gravitas and quick wit in equal measure. Unfortunately the regular press conferences became less and less regular as time went on. There was always a good excuse for postponing them. Eric Walsh and I pleaded with Whitlam to keep faith with the gallery, but he was never convinced that the press conferences brought him much favourable exposure.

More to his taste was the national broadcast. Occasionally the television networks would offer the prime minister free time to speak for around five minutes on a matter of national importance. Today, an address by the prime minister would usually be treated as paid advertising and charged for accordingly. In those days, the ABC – even, on occasions, the commercial channels – saw the provision of free time as a public responsibility. How quaint and gentlemanly it all seems now. I wrote a number of these broadcasts for Whitlam, particularly during the first supply crisis in 1974. For a while, too, he could count on free time on Labor-affiliated radio stations such as 2KY in Sydney and 3KZ in Melbourne. In the pre–talkback radio era, it was not a bad alternative to an interview with Alan Jones.

For Whitlam it was always the speech that mattered; and the speech that mattered most was the parliamentary setpiece, delivered to a full and attentive house. With his usual taste for self-mocking bombast, he liked to refer to his speeches as orations. “Where’s my oration, comrade?” was a frequent last-minute demand before a public performance. The speech was his principal mode of communication with the wider electorate. Copies of speeches were circulated to reporters covering public events and distributed to the gallery. If there was an announcement to be made, it would be there in the speech, and journalists would know where to find it.

I had begun writing for Whitlam even before joining his staff. In late 1972, I rejoiced in the title of associate editor of the Australian and the Sunday Telegraph, and Labor supporters numbered Rupert Murdoch among the angels. The Australian and other Murdoch newspapers campaigned for a Whitlam victory. In between writing pro-Labor editorials, I joined Freudenberg in drafting some of Whitlam’s campaign speeches. One of them was for the final rally at St Kilda Town Hall on the Thursday before the election. The speech was vetted and approved by Murdoch. Whitlam, wisely, threw it away and spoke off the cuff. But it wasn’t one of his best efforts.

Despite the emotional impact of the “It’s Time” launch at Blacktown, he always felt uncomfortable with political rhetoric. We did our best to persuade him to make his campaign speeches less dry and fact-laden. It was a standing joke among staff during the 1972 campaign that Whitlam would rather talk about the Concrete Pipes case in the High Court, or the Commonwealth Industrial Court’s decision in Moore v Doyle, than the ineptitude of prime minister Billy McMahon. Often he would lose his audience, but always they hung on and listened adoringly. “More bullshit, Gough!” Walsh used to plead, “more bullshit.” Lindsay Tanner’s strictures about the dumbing-down of politics and the media would have seemed quite pertinent to an observer in Whitlam’s office forty years ago.

He rarely altered a speech that was given to him. Occasionally he would make a note on the opening page to prompt some anecdote or digression, but generally he stuck to the text. The longest speech I wrote for him was delivered in the House of Representatives in December 1973. I had been asked to prepare the text of a booklet summarising the government’s achievements in its first year. Whitlam intended to table it in the House and have it incorporated in Hansard for the record. The opposition refused to provide leave so it could be tabled. Whitlam immediately used his numbers to obtain leave to make a ministerial statement and read the document in its entirety, including all its lists and appendices. It took him more than two hours. Opposition members, eager to board flights home for Christmas, were compelled to stay and listen.

But like all the best politicians, he could extemporise when necessary. I remember a disastrous day in 1975. Labor had lost the Bass by-election in humiliating fashion and Whitlam was on his way back from Tasmania to Melbourne, where he was due to address a luncheon meeting of the Victorian Farmers Federation. His car stopped in Collins Street. Whitlam and I got out and the driver at once sped off out of sight. After it was too late, I discovered that I had left the speech in the back of the car. No mobile phones. No spare copy. Whitlam charmed his audience with twenty minutes of ad-libbed pleasantries while the car was located and the speech retrieved. I had the unenviable duty of passing it up to him on stage. All was later forgiven.

That forgiveness was typical. He made exacting demands on his staff, but his tantrums evaporated as quickly as they came, and I never knew him to bear a grudge. He addressed us all, affectionately enough, as “Comrade,” and for a few there were nicknames. Darlow was “Ruv,” a “Chinese” version of “Love”; Wilenski was the “Doctor”; Freudenberg’s name was anglicised as “Mountjoy” (more a play on words than a form of address), and I was greeted on occasions as “François,” the French form of my first name Frank (to which I would respond, as expected, with Edouard). In normal office dealings we addressed him as “Leader” – no one, apart from Walsh, dared to call him Gough to his face.

But such formalities meant little to him. Whenever he blew his top, the cause would invariably be some act of negligence or carelessness, some lapse of routine diligence, rather than any show of folly or ignorance. The “spectacular irascibility” of which Mathews wrote could be frightening while it lasted, but it never lasted long. The withering reprimands, the teeth-grinding invective, soon blew themselves out. Even so, those of a sensitive nature, or unwilling to believe that Whitlam’s displays of fury might be largely synthetic, were well-advised to keep out of his way. Members of the so-called “Polish corridor” – Wilenski, Spigelman, Freudenberg – enjoyed a measure of immunity, but female staff were by no means exempt from the worst outbursts. Darlow remembers a day when Wilenski’s secretary, a quiet woman called Rita, hid under a desk to escape a tirade directed at the office in general.

And yet we loved him. The Whitlam office is perhaps the best example of how a close-knit staff, under-resourced and working under extreme pressure in difficult surroundings, can function with harmony, discipline and a shared sense of purpose. It is pointless now to ask why it all went wrong. The story has been told many times. All of us will draw our own conclusions. Whenever governments are in difficulty, the first reaction of loyal supporters is to blame the communicators. Why are we failing to get our message across? How often I heard those words from ministers or caucus members. No doubt we communicators must accept our share of the blame. But perhaps the fault, dear reader, lay not in ourselves but in our message that we stuffed things up so badly. It will always be our glorious consolation that the Whitlam legacy endured, that its great story of rejuvenation and reform can still be seen and felt today. For those who toiled briefly in the vineyard – or, as Gough would say, for “all of you who cling to the hem of my garment” – it was a grand time while it lasted. •

This essay appears in The Whitlam Legacy, edited by Troy Bramston, which can be purchased from The Federation Press.