Cao Fei wrote her first email in 2000. It was her first encounter with the internet, a medium that as an artist she would soon make her own. To get her message into cyberspace, she had to ask around among her friends till she found one whose parents had an email account. It was on their computer that she wrote her first “artist’s statement.”

She had been asked by a curator to explain the ideas behind her first film, titled Imbalance. She had made it the year before on a borrowed DVD recorder, casting her classmates at the Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts in a study of “restless adolescence.” In a competition in Hong Kong it had caught the attention of curator Hou Hanru, who chose it for a photography festival in Madrid.

Hou was attracted by Cao Fei’s filmmaking flair, the skewwhiff camera angles and tracking shots. But what struck me when I saw Imbalance years later was how free her classmates seemed to be, despite their adolescent angst, how mockingly they faced the world. The whole thing read like an advertisement for the pleasures of “spiritual pollution.” All the things that had agitated the Communist Party’s Old Guard back in 1983, all the toxins they had sought to expel from China – “pornography,” drugs, gambling – were there, and not even as the main point of the film, but just as part of the background of these college kids’ lives.

They were enjoying the luxury of adolescence – an indulgence that was still new to China – in a city that was booming and open to the world. Guangzhou was the capital of Guangdong province, which by the year 2000 was producing 42 per cent of China’s exports and attracting the majority of the country’s foreign investment. Workers were flocking to the factories of the Pearl River delta, and by the turn of the century Guangdong province was home to a third of the 144 million workers who had left their villages in search of a new life.

The south was being transformed socially and physically, and this was the subject of Cao Fei’s next project. Through the 1990s she watched as her home town grew, rolling out into the countryside, turning fields into factories, farms into condos. As Guangzhou expanded it began to swallow entire villages whole. The farmers would lose their fields but keep their houses. Robbed of their old livelihood, they built tenements on top of their homes and set up as landlords, offering cheap accommodation to the floating population of workers who had left other farms around China to find work in the city.

Villages that had once been home to three or four thousand people now housed ten times that number in these strange pockets within the city. Slipping down an alley off a main street you could find 130 such urban villages in Guangzhou, with the tenements crowded in so tightly that sunlight reached the ground only in shafts, and the old village life continued side by side with a whole new service economy for immigrants. Long-distance phone offices sat side by side with nail bars, dumpling shops and workshops that restored discarded white goods for sale. The landless farmers planted vegetable crops and raised chickens on their roofs. On feast days, traditional dragon dancers squeezed their way through the narrow alleyways. One of these villages – a place called Sanyuanli – became the subject of Cao Fei’s first major documentary film (produced in association with her then boyfriend, the artist and writer Ou Ning) in 2003.

Cao Fei saw the face of her home town transformed. She was gripped by cities, and in the new century she returned to urban landscapes again and again, creating whole fantasy cities on video, in animation and on the internet, while taking her camera out to explore real cities in her documentaries. In all of these she was working out how people live in these urban spaces, and while living there how they could still find a way to dream.

By the turn of the century, with more than 10 per cent of China’s population on the move, many itinerants found themselves working in appalling conditions. Exploitation was rife in the factories and much of the alternative urban work was dirty or dangerous. And yet those who came still believed they had made the right decision by leaving home.

Despite booming profits, non-payment and underpayment of wages was rife, as were inhuman hours of work. Research by the Communist Party Youth League found the majority of factory workers in Guangdong worked twelve to fourteen hours per day with rarely a day off. Conditions were particularly severe in the garment industry, where pressure to fill orders pushed conditions to new extremes. A new word, guolaosi (“overwork death”), entered the language to describe cases where workers dropped dead of exhaustion. The Chinese press reported twelve or more cases per year of guolaosi in the early years of this century, while deaths due to industrial accidents were reported to be occurring at a rate of one every four days in Shenzhen during 1998. Incidents of serious injury were also common, with Amnesty International counting more than 12,000 such accidents in that same year in Shenzhen.

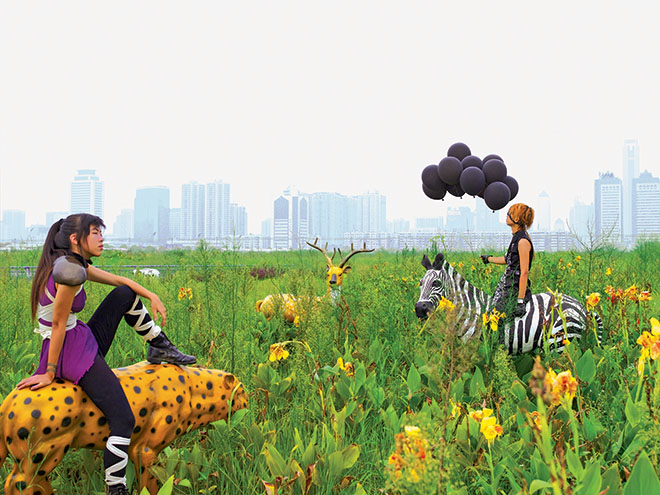

Cao Fei’s Cosplayers – A Mirage. C-print, 2004/Courtesy of the artist and Vitamin Creative Space

The special economic zone of Shenzhen was in the vanguard of China’s transformation into a manufacturing superpower, its GDP growing by more than 30 per cent a year on average throughout the 1980s and ’90s. In the ’90s, Shenzhen would also become a pioneer in labour activism, as workers there tried to enforce the rights that were laid down for them in China’s national labour legislation. These laws, which prescribed conditions such as maximum hours and minimum pay rates, were routinely ignored by employers, but in the ’90s there was an increasing number of cases where workers would, often after Kafkaesque manoeuvrings through the system, achieve limited redress.

Some industrial actions began in almost comical circumstances, as in the case of an export textile factory recounted by the sociologist Ching Kwan Lee in her brilliant study of labour activism in China, Against the Law. In this instance the workers were made aware of their rights when their bosses set out to drill them on the correct answers to give to a visiting inspection team from the factory’s American customers. This was how they learnt of their entitlement to five-day work weeks, eight-hour days, Sundays off and limits on overtime – all entirely absent in their workplace.

China’s Labour Law was enacted in 1994 but, like many other laws passed in the country since the beginning of reform, lofty ideals were not matched with the means (or often the will) to enforce them. Workers’ frustrations over the inability to get what was legally theirs made Shenzhen infamous throughout the country as the worst city in China for labour disputes. By the turn of the century, even conservative estimates suggested that there were hundreds of large-scale protests or strikes breaking out annually in Shenzhen.

Yet, despite the harshness of life in the cities, workers continued to leave the countryside in droves to try their luck. It is the dreams of these workers that have driven the urbanisation of China, turning a country in which 70 per cent of people once lived on the land to one in which more than half live in cities.

The notion of success in the city persisted because most of those who came, despite all the difficulties they faced, did end up better off. Most earned more than they would ever have been able to make at home. This was money that could be remitted to their families or used to fund vocational study or investment in a small business. Then there was the intangible, but exhilarating, gain that they made – a sense of control over their own destiny.

Cao Fei’s father recruited many of these rural itinerants to work with him on the massive sculptures which he was now being commissioned to create. Cao Fei spent hours hanging out with them, listening to the stories of their floating lives. The workers told her how they would fake their identity cards, lowering their age over and over again, as the young always found it easiest to find work. She was fascinated by their stories and curious about their dreams, which she put at the centre of her art when she made the documentary Whose Utopia?

She spent six months in a Guangdong lighting factory charting both the minutiae of the work and the fantasy lives of the employees. In Whose Utopia? the workers pirouette in tutus among the machines, play electric guitar, sweep through store rooms in evening dress, and dance like Gene Kelly across the shop floor. Young workers look out dreamily over the rooftops of the city and don T-shirts with the slogan “My future is not a dream.” For Cao Fei the message of her film was clear: even when life is difficult or boring for people, their dreams can give them some power.

But when Whose Utopia? was released, audiences saw it as a commentary on the cruelty of capitalism, the fantasy elements inserted to highlight the workers’ wretchedness. She was hoping that they would see something more complex. When she talked to the workers, she discovered that rather than feeling exploited, they felt lucky to have escaped poverty in the countryside for a job where they could help their families and themselves. Cao Fei was wry when she told me this, pointing out that it was important to not just see issues from a “correct line perspective.”

Despite my natural cynicism as a journalist, I knew immediately what she meant: I had been there myself. In 1996 I had teamed up with ABC TV’s new China correspondent, Jane Hutcheon, to tell the story of China’s floating population. We had decided to look at it through the eyes of a young rag-picker from Anhui who we had found living on the fringes of Beijing. He had sunk all his resources into a pedal cart on which he scoured the city collecting cardboard, plastic bottles, cans and every other kind of rubbish that could be turned into cash, selling it on for tiny sums to professional recyclers one rung up the economic ladder from him.

Yet he was managing to house and feed his wife and child on the money he was making, as well as sending some funds home to his parents and saving a little, too. When we travelled back with him at Chinese New Year to his home in a hardscrabble village in the heartland of Anhui, we saw him greeted like a hero and glowing with happiness at his parents’ evident pride. We saw the benefits his remittances had brought – in the quality of the food his parents ate, and in the improvements to their house. Nearby we saw the local version of a mansion being built. It was owned by a man known as “Mr Shanghai,” named after the city in which he had made his fortune. In this village everyone but the old or the very young had either left for the cities or were planning to do so. It was hard to deny the power of the urban dream. •

This is an edited extract from The Phoenix Years by , published this month by Allen & Unwin.