THE French composer Henri Dutilleux, who died in May aged ninety-seven, was a traditional composer. He had an astonishing ear for sonority – reinforcing the cliché that it’s French composers who explore new tone colours – but the great strength of his music was a sure command of harmonic structure allied to an ability to write melodic lines of distinction. Stylistically, his music continued to owe much to earlier twentieth-century composers such as Debussy, Ravel and Stravinsky, and though he developed a personal style, it remained recognisably in the ambit of those earlier composers. Never a rebel, Dutilleux was a lyrical composer with a great love of the human voice – of which the new recording of Correspondances (2003) sung by Barbara Hannigan offers a striking example. Somewhat uncomfortable in the public gaze, Dutilleux kept his head in his scores, of which there are regrettably few, fastidiously revising his pieces until he was happy with them. As a result he was never a household name, not even really in his homeland.

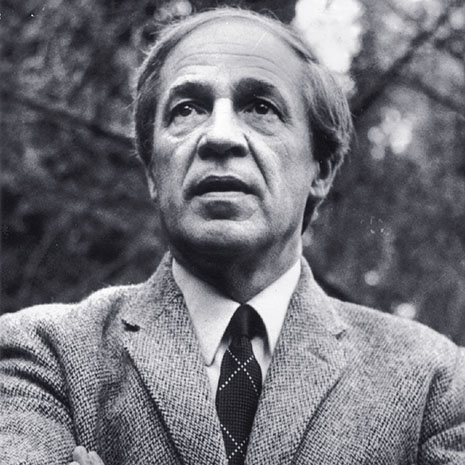

In all respects bar one, then, he couldn’t have been more different from his compatriot and near contemporary, Pierre Boulez (born 1925). Since his twenties, Boulez has given interviews, made speeches and written articles advancing trenchant views on his own music and the music of others, sometimes to the point of insensitivity. Boulez’s composition, though impossible without the same precursors that influenced Dutilleux, has always pursued a consciously radical agenda. The complexity of some of his early pieces, notably his great masterpiece of the mid 1950s, Le marteau sans maître, forced him to take up conducting, and it wasn’t long before he was running orchestras.

These days, Boulez is a grand old man of the podium – a very public figure. But the thing he has in common with Dutilleux is that fastidious ear and rigorously self-critical nature. Neither Dutilleux nor Boulez could ever have been called prolific, and a new boxed set entitled Boulez: Complete Works, runs to just thirteen discs. This, moreover, includes a disc of duplications in the form of historical recordings, and an interview disc. That’s slim pickings, you might think, from a composing career that stretches from 1945 to the present. Benjamin Britten’s complete works, also just out, stretch to sixty-five discs, and he lived a much shorter life than Boulez. Bach’s music requires in excess of 150 discs.

But there is a unique aspect to Boulez the composer. It is not just that he is self-critical and therefore slow. Some of his pieces have been composed rather quickly. No, it’s that Boulez can always see other possibilities. Of the thirty-odd pieces in this beautifully produced collection, around a third are not really finished. The front of the box might read “Complete Works,” but turn it over and you find a different title: “Works in Progress.” That’s more like it.

“More than anyone else’s,” Claude Samuel writes in the exemplary program book, “Pierre Boulez’s oeuvre has not known completion and never will.” Sometimes it’s been a matter of one thing leading to another. Répons, an ambitious piece for large ensemble with satellite soloists, each hooked up to technology that moves the sounds in time and space, was first performed in 1981 in a version lasting seventeen minutes. By the following year, it had grown to half an hour. In 1984 it lasted forty-five minutes (that’s the current state of play and the version recorded here), but Boulez has said he believes Répons should be twice as long as that.

Meanwhile, the harmonic kernel of Répons – which it already shared with a piece for multiple cellos – was further explored in a short chamber work, Dérive – six minutes of music for six instruments. In turn, this spawned Dérive 2, for eleven instruments, which lasted twenty minutes in 1990 but now lasts forty-five (and, mark you, forty-five minutes of brilliant, often very, very fast music – hundreds of thousands of notes). According to Claude Samuel, Dérive 3 is already being sketched.

You get the idea. It’s not that Boulez can’t let go – not even that he doesn’t want to – but that he continually finds new paths and won’t abandon the material until he feels its potential is fully realised.

Boulez is now eighty-eight and apparently frail. His eyesight is failing, obliging him, in the past twelve months, to cancel nearly all conducting engagements. This could, I suppose, be good news for his composing – composers, after all, can always dictate – but one fears and suspects that most of his works in progress will remain that way, and that oft-mooted projects such as a violin concerto for Anne-Sophie Mutter and an opera of Waiting for Godot will never happen.

I find this sad, though I doubt that Boulez does. The composer has a reputation for being fierce. Some have called him megalomaniacal. That’s not my experience. I have interviewed him a few times, and always found him kind and courteous. A couple of friends who know him tell me that his loyalty to colleagues has sometimes been to the detriment of his own work. A conductor friend falls ill, Boulez (who has never had an agent) is rung up, and before you know it he is stepping in to conduct this Stravinsky concert or Mahler symphony – or Mahler cycle. Meanwhile there is all that unfinished music, and probably always will be.

Boulez will likely be the first major composer in the history of classical music to give no heed to the concept of Great Works. He has never bothered with opus numbers. When he dies, what is left will be what is left.

Meanwhile we have thirteen CDs, which, though a model of how such projects should be realised – superb recordings, a long interview, a provocative essay, full printed texts and translations, lots of photographs – doesn’t feel quite enough. •