This year marks the 150th birthday of Maurice Ravel and the centenary of Erik Satie’s death. The French composers knew and admired each other and their names appeared as dedications at the top of each other’s scores. Ravel, the younger man, was always happy to admit Satie’s influence — especially harmonic — on his music and Satie was mostly pleased to hear it. That said, there are many more differences between them than points of similarity, and the posthumous reception of their music bears this out.

Erik Satie (1866–1925) is the composer of a handful of piano pieces that have become familiar to the point of cliché, especially in films. Most people would recognise two or three pieces from the sets known as Gymnopédies and Gnossiennes without necessarily being able to name the composer; those who know the name would likely be unaware of the rest of his work (much of it very different in nature), because it is so seldom heard.

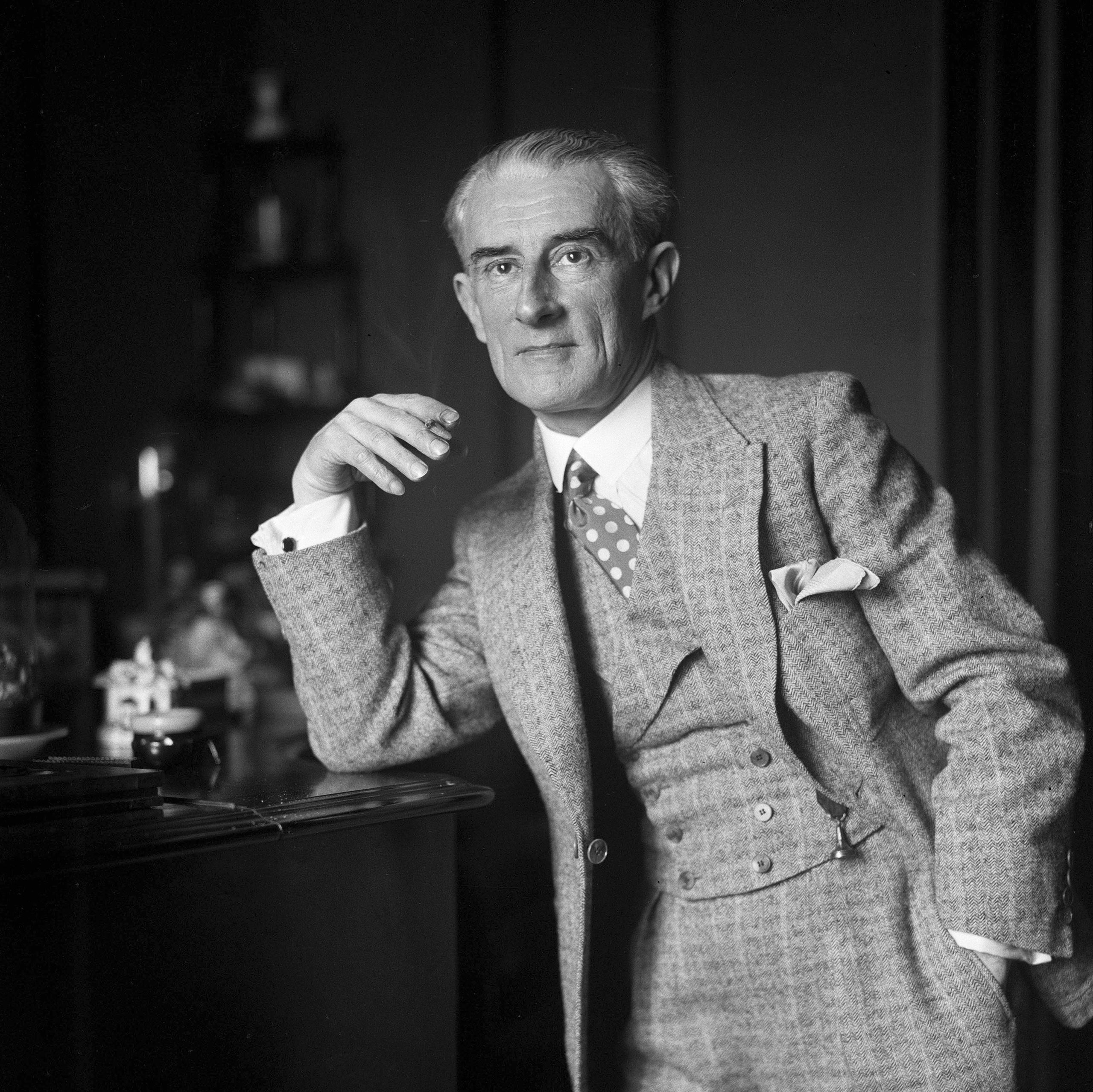

Maurice Ravel (1875–1937) is another story. Widely known as the composer of Boléro (another kind of cliché, to be sure), he wrote a dozen more orchestral works, including a couple of piano concertos, songs, chamber music and solo piano pieces that regularly turn up in concert halls around the world, and not only this year. Where Satie was a musical radical — John Cage once said “without Satie, we can do nothing” — Ravel, for all his sonic innovation, was essentially a mainstream composer.

Two recent publications mirror their composers’ musical personalities. Emily Kilpatrick’s Maurice Ravel is a miracle of a book, a life and works that produces numerous revelations on both counts in under two hundred pages. An Australian musicologist and pianist at London’s Royal Academy of Music, Kilpatrick is adept at finding ways to make the composer’s music illuminate the composer’s life. I thought I knew Ravel and his work (especially the work) but had learnt ten or twelve new things by the end of the introduction.

One particularly interesting piece of speculation on Kilpatrick’s part is that Ravel was neurodivergent. He was “a profoundly sensitive and good man” (Léon-Paul Fargue) made unhappy by disorder, and when his routine was disrupted he would grow agitated. We already knew he was a snappy dresser and there are several reports of his holding up concerts for up to half an hour while the right shoes or cuff links were found.

Dandyism was the accepted explanation, but surely a dandy would know where his shoes were! On one occasion, the hold-up was because a handkerchief had gone missing from his suit jacket. The pianist Robert Casadesus offered his own as a replacement, but it was of no use: the initials were wrong. “It was not that Ravel wouldn’t walk on stage,” Kilpatrick writes, “but that he couldn’t.”

The order he required in his life is everywhere in Ravel’s music, earning him a reputation for aloofness and even sterility. Certainly, when it came to form, he was unsentimental. Asked if the newly composed finale of his Violin Sonata was better than the original, which he’d junked, he replied: “Oh no, I like it much less. But its form is much better suited to the Sonata as a whole.”

But there is a paradox at play with Ravel, for the cool precision of his music barely masks a harmonic underpinning that is profoundly touching. Kilpatrick is good at getting this musical emotion into her narrative. Her discussion of the closing pages of the opera, L’Enfant et les sortilèges (The Child and the Spells), conjured the sound of the music so well it brought a lump to my throat. She is equally adept at the glancing aperçu. In “Le Gibet,” the central panel of the piano triptych Gaspard de la Nuit, the spider spinning “its grisly necklace” round the dead man’s neck is portrayed with punning octatonicism — an eight-note scale.

Ian Penman’s Erik Satie Three Piece Suite is, like its subject, a very different kettle of fish. Penman is a music journalist and “cult critic” (according to the back-cover blurb), his writing about pop music of one sort or another and sometimes about film appearing in the likes of the London Review of Books and Sight & Sound. I enjoyed his collection of essays It Gets Me Home, This Curving Track.

He is not an obvious candidate to write a life and works of Satie and he hasn’t done that. The “three piece suite” of the title is both a pun on the three-piece suits habitually worn by the composer and a reference to the “furniture music” (Musique d’ameublement) he pioneered — ambient music half a century before Brian Eno. It also describes the form of the book, which, though no longer than Kilpatrick’s Ravel, is in three distinct parts: “Satie Essay,” “Satie A–Z” and “Satie Diary.”

Penman’s refreshing approach is that of an enthusiast rather than an expert, though it might have been an even better book if he’d been both. In part one, we warm to the author’s delight in René Clair’s film Entr’acte, for which Satie composed the music (it was shown in the intermission of his ballet Relâche) and in which he features along with Man Ray, Francis Picabia and Marcel Duchamp. Together with Penman we learn about Satie and his work, and the author’s enthusiasm is infectious.

Part two, the A–Z, has entries for “Apollinaire,” “Burgess” (the writer Anthony Burgess, whom Penman admires) and “Cage,” “Demi-Monde,” “Easy Listening” and “Furniture.” There are no fewer than fifteen entries for “Three” and twenty-one for “Vexations,” the title of Satie’s very slow keyboard piece involving 840 repetitions of the same phrase.

The diary of the final part is Penman’s own, kept while researching and writing the book we are reading. Its inclusion is a decidedly self-reflexive move, but then this book is always as much about the author as the composer. I have to say the details of Penman’s dreams are no more interesting than anyone else’s would have been.

Penman is keen, he tells us, to concentrate on the musical invention and downplay Satie’s eccentricities, but that’s a tough call. They are there in Satie’s titles (Three Pieces in the Shape of a Pear), in his instructions to performers (“Behave yourself, please: a monkey is watching you”) and in his lifestyle: he lived in a room not much larger than a cupboard containing two grand pianos, one on top of the other, the upper piano a receptacle for his unopened mail.

Satie’s eccentricity has always bothered me. It seems so arch, and Penman’s book, I have to say, is also a bit like that — but maybe that’s the point. Was the eccentricity a mask, like Ravel’s dandyism? Did it hide a creative spirit struggling with the outside world?

What Penman achieves with his book — and this, surely, must be the aim of any book about music — is to send the reader back to the music itself. But here’s my other problem with Satie. Without doubt, he was a radical composer who made other things possible — Ravel, Cage and Eno would all concur. But do I actually want to hear his music? On the whole, no. I can listen to Ravel any day of the week, but having once more steeped myself in Satie while reading Penman, I find that popular sentiment, as is often the case, has it right: those wistful little piano pieces, the Gymnopédies and Gnossiennes, are the best of him. •