The Abominable Man

By Maj Sjöwall and Per Wahlöö | Translated by Thomas Teal | Fourth Estate | $19.99

“Scandi noir” is the term coined to describe, half-jokingly, a particular kind of bleak and addictive crime fiction that began to emerge from the Scandinavian countries in the 1990s. What started as a niche category, propelled along by two brilliantly absorbing thrillers – Peter Høeg’s Miss Smilla’s Feeling for Snow, which first appeared in English in 1993, followed by Kerstin Ekman’s Blackwater in 1996 – rapidly became a genre all on its own, one that is now instantly recognisable in fiction and on film. It’s a genre illuminated by the pale light of winter, which seems at first to bestow an air of calm and restful silence. We soon learn, however, that this is merely a prelude to the exposure of all manner of violence and cruelty, practised by people who are just pretending to be quiet and civilised. In the novels of Henning Mankell, Stieg Larsson and Jo Nesbø, to name only the most phenomenally successful of the dozens of Scandinavian crime writers whose books are now widely available internationally, as well as in the many film and television adaptations of their work and in original television series such as The Killing (2007) and The Bridge (2011), we follow detectives as they tackle the darkest of human nature’s dark sides. And these are detectives who, typically, have issues, from alcoholism to Asperger’s and on through the rest of the alphabet.

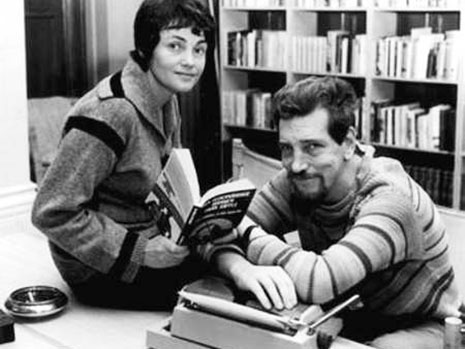

Henning Mankell is one of the many exponents of the new Scandinavian crime fiction to have traced the genre’s origins back to the Swedish writing partnership of Per Wahlöö and Maj Sjöwall, who between them produced ten novels – one a year between 1965 and 1975 – featuring the lugubrious detective Martin Beck and a cast of flawed, uncooperative but, in their own idiosyncratic ways, effective colleagues. Wahlöö died, at the age of only forty-eight, in 1975, shortly after the publication of The Terrorists, the novel that completed what he and his co-author described as a “Decalogue.” Today, Sjöwall continues to write and to undertake translations; she has also served as a consultant on the long-running series for Swedish television, Beck (now available, incidentally, on DVD, with subtitles).

“I think,” says Mankell of this influential literary partnership, “that anyone who writes about crime as a reflection of society has been inspired to some extent by what they wrote.” The Norwegian crime writer Jo Nesbø is equally happy to assign credit where it is due. “Everyone in Scandinavia who writes a crime novel,” he said in a recent interview, “whether they know it or not, they are influenced by Maj Sjöwall and Per Wahlöö.” The influence goes beyond Scandinavia. The British writer Lee Child provides the introduction to The Abominable Man, the seventh in the series and among the latest to be re-issued by Fourth Estate. Child describes Beck, with his rumpled determination, “as the grandfather of practically all current Scandinavian detectives, as well as foreigners as far-flung as Ian Rankin’s John Rebus and Martin Cruz Smith’s Arkady Renko.”

Sjöwall and Wahlöö both had backgrounds in journalism and in radical politics, and Wahlöö had already published several books on his own, when the pair met and became lovers in the early 1960s. Together they developed, with a kind of mathematical precision, a plan to produce ten (and only ten) novels under the general heading of “the story of a crime.” The crime in question referred not to the anchors of the plots – the murders and assaults and acts of terrorism that feature in abundance – but to the generic crime perpetrated by the state against the individual, and to the ways in which ordinary and in particular disadvantaged lives are manipulated and very often discarded by those who have chosen, or been seduced into, exploiting the structures and mechanisms of the state for their own ends. What Sjöwall and Wahlöö identified in the Swedish political landscape was the way in which the focus of daily life was shifting from the local community to the overarching state, a process exemplified for them by the nationalisation of the police force in 1965. What might be referred to today as community policing became what the two writers saw as a mechanism for accumulating power over individuals too weak or too weakened to fight back.

It is difficult to know quite where the character of Martin Beck stands on all this. He is a policeman, and to that extent part of the system. But he often seems to be as much on the side of the criminal as of the victim, particularly as we witness his growing understanding of the motivations that lie behind the mysteries he is required, along with his colleagues, to solve. The Abominable Man opens with the brutal and bloody murder in his hospital bed of Chief Inspector Stig Nyman. The weapon is a carbine bayonet, and by the time the murderer is finished the chief inspector is virtually unrecognisable. “Whoever did this must be raving mad,” observes Beck’s colleague as he and Beck contemplate the body. “Yes,” says the more circumspect Beck, “it looks that way.” His reservations turn out to be prescient. Nyman, it transpires, had a reputation for corruption and intimidation and violence. He was, in fact, an abominable man. It is not surprising, therefore, that someone might have wanted to murder him.

Beck has these occasional flashes of intuition, but he is far from being the all-seeing detective supremely confident in himself and his own judgement. He is no Hercule Poirot, whose closest brush with an existential crise is when he spies a speck of dust on his patent leather shoe (though Beck does, like Poirot, suffer from a delicate stomach; in detective fiction, there are always unbroken lines to be found, descending from even the most unlikely ancestors). Beck is neither outstandingly clever nor very brave. “Yes, he was a coward,” he muses in The Abominable Man, describing himself as if from the outside. Indeed his ordinariness is established from the very beginning. In Roseanna, the first novel in the series, he is introduced as “thin but not especially tall and somewhat round-shouldered. Some women would say he was good looking but most of them would see him as quite ordinary.”

Over the ensuing novels Beck seems to become, if anything, even less prepossessing. He often has a cold. He is always tired. In The Abominable Man, his marriage has failed and his social circle has become even more limited. He “suffers from claustrophobia and aversion to crowds.” And yet, in contrast to Nyman, for whom other people are there simply to be exploited and crushed, Beck retains a sense of “responsibility for human beings.” As further details of the victim’s life unfold, he feels “something growing stronger and stronger in his mind.” It is a sense of guilt, not for the murder itself, but for participating in the society and the organisational culture that allowed Nyman to do what he did, to destroy so many lives, including that of his eventual murderer.

As the “Decalogue” progresses, Sjöwall and Wahlöö grow politically more outspoken. By the time of The Abominable Man there is an unresolved tension between their characterisation of the police as “a private army,” intent only on increasing its power and looking after its own – “when a member of their own troop meets with misfortune,” the authors comment sardonically, “the police seem to acquire many times their usual energy” – and their sympathetic understanding of the reality of day-to-day police work “built on realism, routine, stubbornness and system.” What Sjöwall and Wahlöö seem to admire most, and what for them stands most effectively against the anonymising power of the state, is the commitment, exemplified by Beck and by certain of his colleagues, to sheer, methodical persistence. Beck accepts that “most of his work was in fact pointless,” but every so often he gets a result, and more of the pieces start to fit together. His hobby is building model ships. In The Abominable Man, he is working on the Flying Cloud, with only the rigging left to do. The rigging, we are told, “is the most difficult and trying part” but we are left in no doubt that Martin Beck will complete the task. •