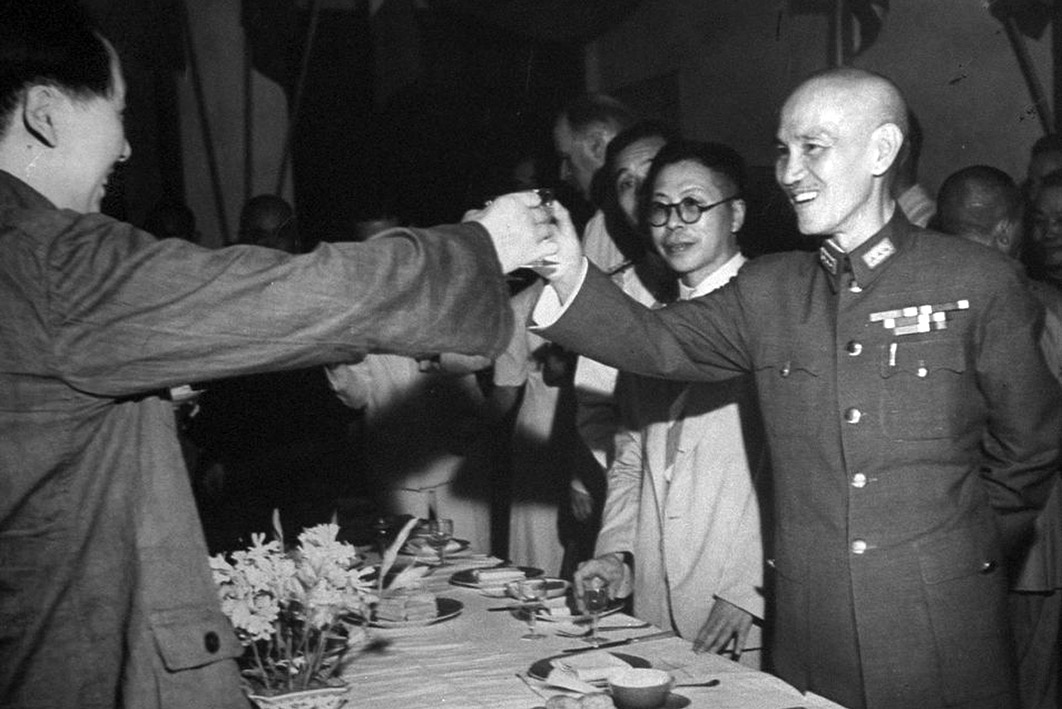

Could the Chinese civil war of 1945–49 have been avoided? Might a negotiated solution have paved the way for power sharing, even democracy, in China, and avoided the all-or-nothing outcome that saw Chiang Kai-shek swept from the mainland and Mao Zedong enthroned in his place?

Like journalists Richard Bernstein and Daniel Kurtz-Phelan before him, the Australian historian Victor Cheng is intrigued by that old but still important question. His new book, China Between Peace and War: Mao, Chiang and the Americans, 1945–1947, joins a wave of recent scholarship re-examining a critical moment in Chinese history: the interregnum between the end of China’s war with Japan and the full outbreak of the civil war that would see the Chinese Communist revolution and the creation of the People’s Republic of China in 1949.

Cheng sheds new light on this question by connecting a detailed, deeply researched history of these pivotal years with a field of scholarship and research rarely examined in detail by historians: studies of negotiation and mediation. Drawing on archival sources from the United States, China and Taiwan, along with documents and published sources in English, Chinese and Japanese, he connects his historical research with a large number of social science studies of negotiating tactics and dynamics. He then reassesses the decisions of many of the central participants: Chiang, Mao, his deputy Zhou Enlai, and American general George Marshall, who headed a major if ultimately doomed effort to broker peace between the two sides.

In doing so, Cheng argues that a violent resolution of the Chinese civil war was not inevitable. All parties, including Mao and his Chinese Communist Party, took the negotiations seriously and had their own motivations for at least exploring what could be gained from talks (even if that was, most often, time). The talks were not just a prelude to the fighting of 1947 and after; the Communist Party, for example, knew there was huge anti-war sentiment in China and was determined not to be blamed for a return to internecine conflict.

This is an important argument that differs from the conclusions of Bernstein, Kurtz-Phelan and many scholars. Cheng’s diligence and honesty as a scholar, though, leads him to present a good deal of evidence that leads the reader to question his argument. Chiang and Mao are often shown talking out of both sides of their mouths, seemingly open to a political settlement while invariably looking to use negotiations to better their position on the battlefield or in the balance of power between Chiang’s Kuomintang and Mao’s Communist Party. Cheng chides not only their duplicity but also their sub-optimal approaches to negotiations — both of which are probably fair assertions — but he falls some way short, in my reading at least, of showing that talks really did offer a viable way out of this struggle.

Some of Cheng’s most insightful analysis, for example, unpicks how the Kuomintang’s legitimacy as a nationalist, anti-imperialist force hamstrung Chiang’s ability to convince the Soviet Union to maintain its support for his role as China’s national leader or to make a sincere offer of power sharing that could have persuaded Mao to order his troops to stand down. Chiang seems to have known this at the time but could not bring himself to compromise Chinese sovereignty in order to better his position in the struggle with Mao.

Cheng’s focus on negotiations is illuminating, both by taking seriously the consequences and possibilities of the Chongqing talks and by bringing in insights about all participants’ behaviour from academic literature on negotiations. But sometimes, in the process of doing so, he somewhat loses sight of the larger historical context.

For example, he gives General Marshall credit for succeeding in the goal the US president Harry Truman had set: to broker a ceasefire between the Kuomintang and the Communist Party. But, as may yet be shown in Ukraine in our time, this misses a larger point: negotiations are a continuation of war by other means. Truman may have told Marshall to get the two sides to stop fighting, but a general who had been Army chief of staff during the second world war (and would give his name to the Marshall Plan) knew that his real objective was a political settlement that protected the interests of the US-backed Kuomintang, prevented a Communist takeover of China, and ended a conflict that had weighed heavy on US taxpayer dollars and international political capital. Cheng cites a “grateful letter” from Mao to argue that Marshall had overcome his “biased stance towards Chiang’s government.” In retrospect, we might think that a thank you from Mao tells us everything we need to know about whether Marshall had truly been successful.

Historians who study or teach this period will nonetheless gain a good deal from reading Cheng’s account. Among many insights, his research adds further weight to Zach Fredman’s argument that it was not only tension between Chiang and US leaders — Marshall and, behind him, President Truman — that undermined the Kuomintang’s partnership with Washington but also myriad lower-level frictions and clashes between US personnel in China and the Nationalist Chinese they had earlier been allied to.

Readers will also appreciate Cheng’s serious engagement with one of the major surviving products of this conflict: Mao’s theory of war. He shows that Mao’s shift to “decisive war” in this period was less a redefining of the communist leader’s overall strategy of warfighting and more a response to the precise circumstances of the Manchuria campaign of 1945 — and anyway a shift in political rhetoric rather than military strategy.

Cheng’s deep research further shows exactly how limits on the Kuomintang’s access to US and international arms — both before and after Truman imposed a formal arms embargo in July 1946 — blunted Chiang’s best, US-trained (and formerly US-equipped) troops: it was all well and good arming them with modern US carbines, but without bullets manufactured exclusively outside China (and even without bayonets for close combat) these guns were worse than useless. Cheng’s meticulous research reveals the tangible consequences of US vacillation for Chiang, who had, with US encouragement, geared his forces to a type of warfare predicated on access to materiel that the very same country then ceased to supply. It was not only at the negotiating table that the Americans ultimately walked away from Chiang and from China.

Cheng’s book is careful and thoughtful scholarship. Whether or not he convinces the reader that there could have been a negotiated peace in China in the 1940s, his focus on these consequential talks nonetheless offers a serious reconsideration of the complex interplay of forces — both political and military — that brought about the world-changing communist victory in China. •

China Between Peace and War: Mao, Chiang and the Americans, 1945–1947

By Victor S.C Cheng | ANU Press | Free online, $50 in print | 290 pages