It was my father who told me about Ginette Neveu. I’d have been in my early teens and, in my memory, we are listening to her play the Mendelssohn violin concerto. That can’t be right, though, because she seems never to have recorded the piece, so I don’t know what prompted him to recount her story more than twenty years after her death. Perhaps we were listening to someone else play the concerto; perhaps the minor-key yearning of the music made him think of her.

The French violinist Ginette Neveu was classical music’s Buddy Holly, an international superstar who died at thirty when her passenger plane crashed into a mountain, and my dad’s account of the event has remained with me. Neveu may not have recorded the Mendelssohn, but her recordings of the concertos by Brahms and Sibelius still take a lot of beating; indeed, she was a particular exponent of Sibelius’s violin concerto. Listening now to her recording from 1946, what I find so interesting is how the mournful opening of the piece seems to have moulded itself to her fate. It is impossible to listen to the first movement without thinking of her untimely death. Come to think of it, the same goes for her Brahms.

With rock music, we half expect our favourite artists to die young. In “My Generation,” The Who’s Roger Daltrey expressed a desire for early extinction, although providence failed to deliver it, and Daltrey and the song’s writer, Pete Townshend, are now both in their early seventies. What’s more, from Janis Joplin to Jimi Hendrix, Tupac to Amy Winehouse, early death has enhanced many a reputation. We may tell ourselves that in the commercial world of rock music, where celebrity is more important than talent, the evanescence of the former is arrested by early death; we may believe that in the classical concert hall the music’s the thing. But we’ll be having ourselves on.

For one thing, showbiz has been part of so-called “serious” music from the start (at the first performance of Beethoven’s violin concerto, the soloist paused, mid-work, to play a novelty of his own devising while holding his instrument upside down). For another, early deaths are just as common in classical music and at least as mythologised – and I’m not even thinking of composers such as Mozart, dead at thirty-five, or Schubert, thirty-one, or Mendelssohn, thirty-eight.

The Romanian pianist Dinu Lipatti, whose centenary fell a few weeks ago, died of causes related to Hodgkin’s disease at thirty-three. He left us rather more recordings than Neveu but, like the violinist, has become associated with certain items in the repertory. In Lipatti’s case, we think of his Chopin first, and perhaps in particular the waltzes, which have seldom seemed more wistful than under his fingers. But is that impression a result of knowing the pianist’s story? Might his Chopin seem less wistful if Lipatti had lived to old age?

In his mid thirties, the Englishman Dennis Brain was generally agreed to be the world’s greatest player of the French horn. Then, one night in 1957, driving to London from a performance at the Edinburgh Festival, he crashed his car into a tree. Brain’s recordings of the Mozart concertos with Herbert von Karajan had brought those pieces to a wide audience, but it is possibly Britten’s Serenade for Tenor, Horn and Strings that more people associate with him. Brain made two recordings of the piece with the tenor Peter Pears, one conducted by the composer, and if you know Brain’s story, it is hard to hear any horn player perform the solo Prologue and off-stage Epilogue, with their wondrously “out-of-tune” natural harmonics, without thinking of the young man for whom they were written.

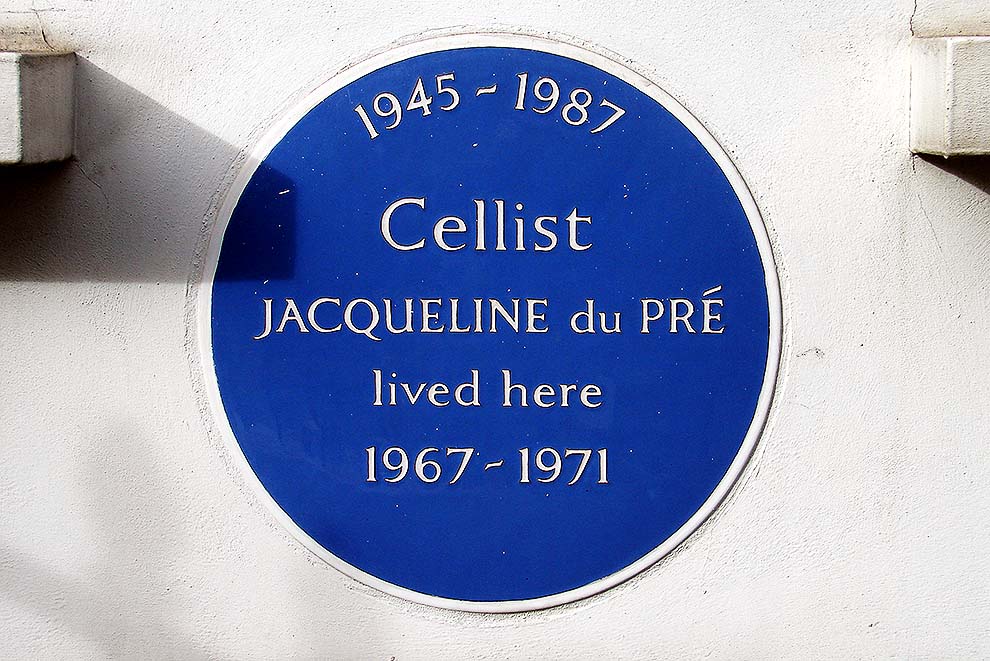

A little nearer our own time, the cellist Jacqueline du Pré was obliged to retire from the concert stage at twenty-seven, suffering from the early effects of multiple sclerosis. It was 1973 and her career was barely a decade old, yet she had already established herself as a great player, her Elgar concerto with John Barbirolli remaining one of history’s most celebrated recordings. She was just twenty at the time, but the LP made both her and the concerto famous. Later, she recorded the piece live with her husband, Daniel Barenboim. No one before had played this piece with such full-toned passion, and few since have come close. Still, the tragedy of her retirement (she died in 1987) undoubtedly gives the recordings a special power.

The list goes on – pianists William Kapell (plane crash), Noel Mewton-Wood (suicide) and Richard Farrell (car crash) were all thirty-one – but, among the household names, Kathleen Ferrier has a special place.

With singers, we already feel that much closer to performers, because they are their instrument, and Ferrier’s voice was completely distinctive. She was a proper contralto – today they’re almost an extinct species – and her voice seemed to come out of the earth. Ferrier died of breast cancer at forty-one, so she wasn’t exactly young, but her career had begun late and, like du Pré, she didn’t have much more than a decade in the limelight. In that short time she sang old music and new (Britten composed for her voice), opera, oratorio and folk songs, but her most famous recording is of Mahler’s Das Lied von der Erde – “The Song of the Earth.” She recorded it in 1952 with Bruno Walter, a colleague and friend of Mahler’s, who had conducted its first performance forty-one years earlier, just a few months after the composer’s death.

After Ferrier’s death, Walter wrote, “The greatest thing in music in my life has been to know Kathleen Ferrier and Gustav Mahler – in that order.” It seems an extraordinary thing to say and we might surmise that Walter was a little in love with the singer, but perhaps, like nearly everyone else, he now simply found it impossible to listen to the final part of Das Lied von der Erde – the “Abschied” or “Leave Taking” – without remembering Ferrier’s rich, deep voice and her life cut short. •