When I tried, in my 2011 Andrew Olle lecture, to describe how I feel about what I do, or what I did until a couple of weeks ago, I co-opted a phrase I’d seen in an article about an American journalist: “joie de journalism.” The same phrase was used three years later when the famous Washington Post editor Ben Bradlee, of Watergate fame, died. Ben, it was said, oozed joie de journalism from every pore.

Well, I’ve had more than half a century of oozing that kind of joy. Journalism is a public service. It lubricates our democracy. It helps keep the bastards honest. It imposes great responsibility on the people who practise it. It matters. But it’s also fun. It’s an adventure. It gets the adrenalin going. There’s nothing like the buzz you feel when you get a big scoop. Political journalism, in particular, deals with intrigue, great drama and fascinating characters. Dan Rather compared journalism with crack cocaine. He’s right.

Politics is also addictive, which is why I thought going cold turkey into retirement might be pretty difficult. But so far, surprisingly, no regrets. The only time I was tempted to reach for the laptop was when I read the story the other day about Malcolm Turnbull delivering a gobfull of obscenity-laden abuse at Tony Abbott on a VIP flight three years ago. It wasn’t exposure of the incident itself that interested me but the claim from a member of the Turnbull media team that the PM does not use that sort of language. It will be a while before I lose the urge to respond to porkies like that.

I’m afraid I haven’t got anything very deep to say today. I thought I’d have a grumble to start with, ramble a bit, then indulge in some nostalgia. It’s what old pensioners do.

It was suggested I might talk about some of the highlights of my career, but two other stories since my retirement have brought back memories of a low point. One was the yarn about Tony Abbott missing key parliamentary divisions in 2009 because he was so drunk no one could rouse him. The other was the election of Philip Ruddock to the post of mayor of Hornsby in NSW council elections at the weekend.

These news items took me back to 1981 and the episode in which I was found to be in contempt of parliament. The reason? I’d had the temerity to suggest that there were drunks and bludgers among the members. Most people have forgotten it. I certainly haven’t.

I was actually trying to be helpful, suggesting in a column in the Sydney Mirror that MPs would be less likely to sit around, feel frustrated and drink if they were given more meaningful work to do through a revamped committee system. Ruddock, then a backbencher, was secretary of the newly formed parliamentary group of Amnesty International and therefore — in theory — an advocate of free speech and freedom of the press.

But he got up in the House, uttered the risible line that parliament was “the most sober working place anywhere in this country,” and moved for an inquiry by the privileges committee into my outrageous assertions. Speaker Billy Snedden, quoting ancient Westminster precedents that allegations of drunkenness were a gross libel on the House, ruled that there was a prima facie breach, and members agreed to the inquiry by seventy-five votes to twenty-seven.

It might seem funny now, but it was no laughing matter at the time. I was a freelancer then. Writing newspaper columns, producing a newsletter, and covering Canberra for a radio network and Ten news, but a freelancer nonetheless. And if they’d taken away my parliamentary pass — which was on the cards — I’d have lost my livelihood.

The privileges committee operated as a star chamber. Proceedings were held in secret. No legal representation was allowed. The Mirror editor, Peter Wylie, hauled before it for running the offending column, was asked if he would be prepared to publish an expression of regret. His response that he would need to consult his superiors brought a warning from a committee member that he could not tell anybody, including legal advisers, what he was asked or what he said.

Fortunately I had the backing of a few principled MPs, including John Spender, who had been a prominent lawyer before entering parliament. I also retained Malcolm Turnbull’s father-in-law Tom Hughes QC, a former attorney-general and the most feared member of the Sydney bar. And there was a backlash. The forces of darkness got cold feet. I was found to be in contempt, but only thrashed with a feather.

By then, of course, I did hold the parliament in contempt. It took me quite a while to get over the collective display of hypocrisy and thuggery and abuse of democratic principles by MPs. For several years I kept pinned to the wall above my desk a list of the seventy-five MPs who had voted with Ruddock. And my contempt for Ruddock himself has never waned.

Some good did come out of the affair. John Spender headed a joint committee that modernised the concept of privilege. As a result, journalists can now report matters like the Abbott binge without risking contempt charges.

It might not have been an earth-shattering event, but the message for me was that it doesn’t take much to push our elected representatives into authoritarian behaviour, especially if their own interests are involved. It was a personal experience that reinforced for me that you can’t just trust these people to do the right thing. You’ve got to watch them. The media has to watch them. And that’s getting harder, thanks to the impact of digital technology.

I happen to think that political journalism is standing up to the digital battering pretty well. You walk into some offices in the press gallery and the thinning ranks are obvious. But the quality of the reporting of politics is still very high. As high as it’s ever been, probably.

This is partly because news organisations have cut back in areas where the effects are least noticeable. The old system of rounds, where journalists developed areas of specialisation and tapped into the bureaucracy, has pretty much gone. That suits the politicians, of course. They don’t want bureaucrats talking to journalists.

But the main reason we’re still getting quality political reporting and investigative journalism despite the cost-cutting and job-shedding, I think, was summed up by Carl Bernstein of Watergate fame a few years ago. “The instinct of reporters,” he said, “is to report.” The job’s been made harder, but good journalists go the extra mile to get it done. That’s what’s happening.

Here’s where I have my little ramble. I want to air a few random thoughts on what’s happening with the media. It’s probably my last chance.

One of the results of the digital revolution is that people now have torrents of information coming at them from all directions. That makes it increasingly difficult to tell what is news, what is personal opinion, what is rumour or gossip, and what is fake. This, of course, makes nonsense of any ideas of journalists as gatekeepers. So what is our role?

I like the answer Buzzfeed’s editor-in-chief Ben Smith gave to David Axelrod in a recent podcast. “We see our role, not as a gatekeeper,” Smith said, “but as a guide helping to navigate through that polluted mess.”

How’s that for journalism’s new mission statement? Guiding punters through the polluted information mess.

I see worrying signs, though, that we’re not doing it as well as we might, or as well as we should. A case in point was the fuss over the photograph of Malcolm Turnbull at the footy nursing his baby granddaughter while sipping beer from a plastic cup.

A few loonies criticised him on social media as an irresponsible childminder. That should have been that. Except that the mainstream media chose to treat the whole thing as news, with headlines about a social media backlash against the PM.

It’s not the first such episode. The kind of dopey or offensive comments that you used to hear at the pub, maybe, now get on Facebook or Twitter, which is bad enough, but then — too often — mainstream media organisations jump in and amplify them. Maybe it’s an attempt to compete with these new platforms. Whatever the reason, allowing Twitter trolls a role in setting the news agenda is not something we should be comfortable with.

Another matter of concern — in my view, one of the most important effects of the digital revolution — is the change it is bringing about in the power balance between politicians and the media. Basically, politicians are coming to the view that they don’t need the media. Increasingly they can operate without us.

India’s prime minister Narendra Modi doesn’t hold news conferences or have much at all in the way of dealings with journalists. We know Donald Trump’s view of the media. He takes that view because he believes he can. Because he believes he can reach the voters without them. More than that — he believes with a fair bit of justification that attacking the media is actually a plus with punters.

And Malcolm Turnbull articulated his feelings pretty clearly in several speeches before becoming prime minister. The megaphone provided by social media, he said in 2013, “means that politicians… do not have to suck up to an editor or a producer to get our views out into the public domain.”

The less politicians need the media, the less ability it has to fulfil its watchdog role.

So it’s not just the loss of revenue and the weakening and fragmentation of news organisations that’s the worry when it comes to the impact of digital technology on political journalism. There’s also a growing threat of irrelevance. Or greatly reduced relevance, anyway.

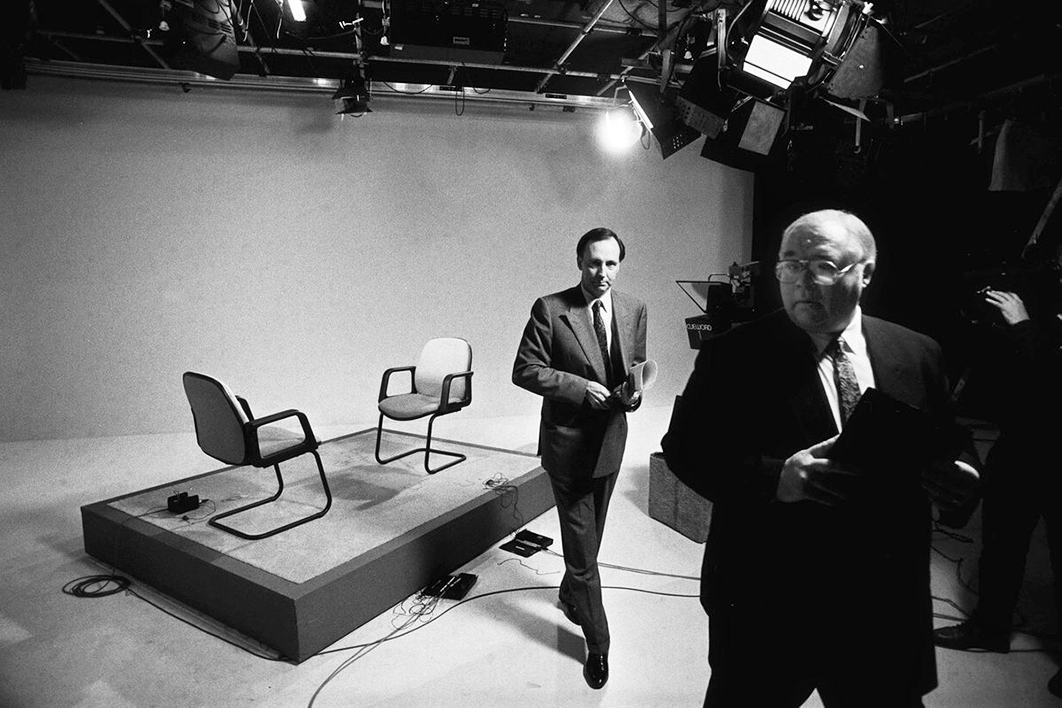

Well, that’s the ramble. Finally, the nostalgia. And what could be more nostalgic than talking about Paul Keating? When I was cleaning out my office in the Nine bureau at Parliament House, I found notes I made of one of his phone calls to me when he was treasurer.

When Paul was annoyed with a journalist — which was pretty often, in my case — he’d ring up and let fly, as only he could. But after a while the abuse would die down and he’d start to talk about what he was doing and what he was thinking and the rationale behind it, and you’d learn. A lot. I never resented those phone calls. I valued them. And once or twice I made close to a verbatim record.

As I reread these notes — of a call from Keating two days before his notorious Placido Domingo speech at the December 1990 press gallery dinner — I realised that much of what he’d said was about how to do politics. And I thought, what a pity Paul doesn’t make one of these calls to Malcolm Turnbull.

One of Malcolm’s problems was summed up by Benjamin Disraeli a century and a half ago. “The world,” Disraeli said, “is wary of statesmen whom democracy has degraded into politicians.” The necessities of politics have prevented Malcolm from being the man we thought he was, and the man he thought he was.

But the current PM’s main problem, in my view, is that he just isn’t very good at politics. He lacks the skills. And he’s not Robinson Crusoe. Political skills, I think, have been in short supply in the post-Howard era. The recent generation of pollies could do with a how-to lecture from Paul Keating.

This particular call was provoked by a column I’d written saying Labor strategists were appalled at the insensitivity and political stupidity of his “this is the recession we had to have” line the previous week. When the familiar voice said over the phone, “You just want to be a bleep” and “Laurie, mate, I can spot a bit of bleepery in a fucking fog three miles away,” I knew I was in trouble. But gradually it developed into a political masterclass.

There was a preview of the gallery dinner speech in comments on then opposition leader John Hewson. “I’m a Placido Domingo,” Keating said. “What the fuck is he? [Meaning Hewson.] He’s an usher. This is the grand stage for the grand performances, and this bloke is just an usher.” A bit tough on Hewson, but the idea of politics as theatre is important.

Gough Whitlam knew the theatrical element was essential. So did Peter Costello. But where are the contemporary politicians with the smarts or the talent to bring theatrical skills back to the political stage?

At another point, Keating told me, “I regard politics as a form of high art.” But he wasn’t talking theatre now. He was talking about the art of political judgement. A judgement on how to handle something like the recession issue, he said, could not be made by a staffer, a pollster or a poll-reader. Only a specialist in the art form — a politician — could do it. And to develop the necessary political artistry, he said, took a good twenty years.

Put aside the innate Keating arrogance. He’s right. Political judgement is something you learn, and it’s in short supply these days. Especially on the coalition side. Malcolm Turnbull, with previous careers as journalist, lawyer and merchant banker, certainly hasn’t spent twenty years developing the art. And doesn’t it show?

Here are a few other lessons in politics — or at least the Keating approach to politics — from this phone call.

Don’t talk down to the public. That, according to Keating, is the greatest mistake many politicians make. “I always talk up to them,” he said. “I always try and tell them what the problem is. I try and explain the stuff.”

Related to that, tell it like it is. “They get up in the morning and see there’s a recession,” he told me. “Keating says it’s a recession they had to have. The people who don’t like me say, ‘The bastard, but he’s probably right.’ The nice ones say, ‘You’ve told us the bloody truth and good on yer.’”

And all this involves courage. “I’m in the crazy brave category,” Keating said. “You’ve got to stand for what you believe.” At another point: “I’m prepared to chance my hand and take the whole show to the wire.” And: “We’ve got to break the fucking inflation rate. It’s not going to be done with some namby-pamby bleep trying to not have a recession.”

I can understand today’s pollies shying away from crazy, but brave would be nice occasionally. I’m damn sure today’s pollies would impress voters a lot more by showing a bit of political guts.

Keating also talked about the need to get policy and rhetoric lined up. What was required, he said, was “long straight lines of rhetoric that stay straight for years at a time.” Isn’t that a great way to put it. And he complained that Bob Hawke kept bending the lines and he had to straighten them out again.

I don’t think Turnbull and Co. would recognise a straight line of rhetoric if they tripped over it.

Finally, even the vivid language Keating used as he spoke to me — I don’t mean the c-words and f-words — were a reminder of the shortcomings of today’s political practitioners.

There was a description of the recession John Howard had presided over as treasurer. “He had a neutron bomb go off. A neutron bomb kills everything that’s living. Leaves the buildings intact but kills everything inside. That’s what Howard did.”

And this: “I pulled the levers in taking the place into recession and I can pull another lever and take it out. When Howard pulled the levers it was like Laurel and Hardy in a motor car. He pulled the bloody handbrake and it came off in his hand. He pulled the fucking steering wheel and it came off in his hand.”

Accessible. Colourful. Memorable. It gets your attention. Compare it with the scripted talking points current politicians learn by rote and spew out on demand.

Keating was right, by the way. His “recession we had to have” approach was the most effective way to deal with that problem. Caution and equivocation would not have cut the mustard.

I have this fantasy. An educational facility to teach young politicians the skills of the trade. With Professor Keating in charge. And the front row of desks reserved for Malcolm Turnbull and his cabinet. •

This is an edited version of Laurie Oakes’s 15 September speech to the Melbourne Press Club. The full text is here.