If only the authors of our Constitution had worded one part of it more carefully. If only the High Court had stopped to consider what those words were intended to say, and how to make them fit the modern world.

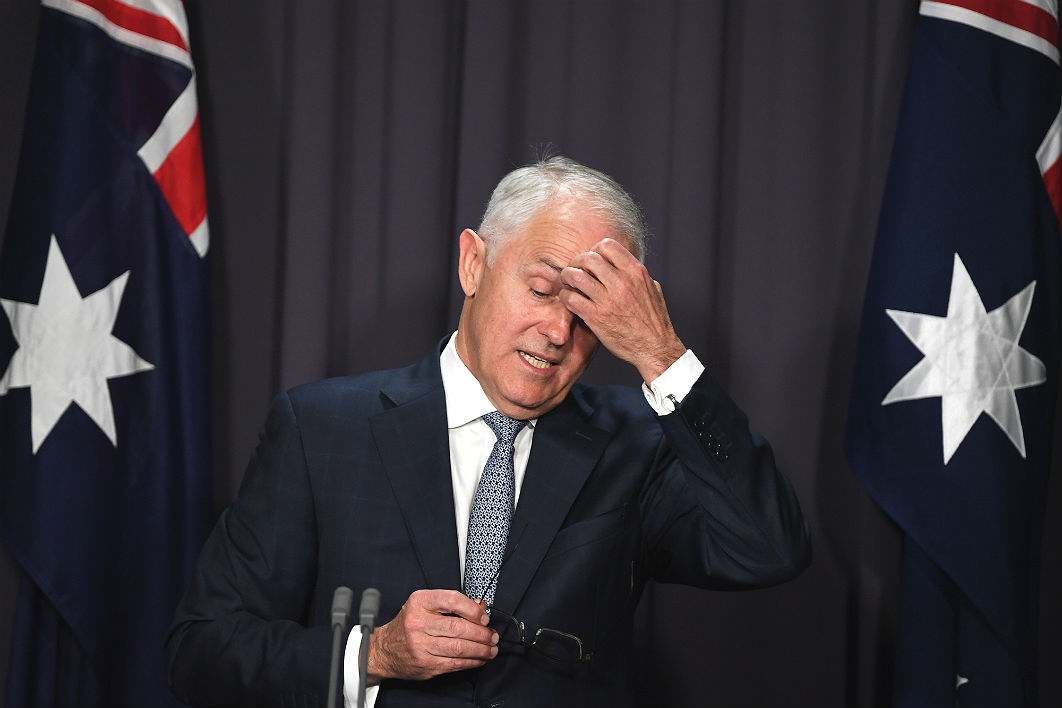

If only past governments and oppositions had united to fix the Constitution’s failure when it was exposed, rather than seeing it as a political opportunity to exploit. And if only Malcolm Turnbull had the patience and political judgement to match his other gifts.

Legal experts say the citizenship saga is not a constitutional crisis. True: it’s just a fiasco. But it is a fiasco caused by a defective Constitution — which, as interpreted by today’s High Court, bans anything up to half of Australia’s population from standing for federal parliament. That’s not what its authors intended.

In part, it is a crisis of the prime minister’s own making, but only in part; he is just the latest in a series of leaders who have refused to fix a problem that has been apparent for decades. The authors of the Constitution must share the blame, and successive High Courts have added their bit to the mess by interpreting the section in rigid ways alien to what the authors intended it to mean.

Why don’t other countries have these problems? They don’t have a section 44(i) in their constitution. And Australia could be rid of this problem too, if its political leaders could unite in asking us at a referendum to delete section 44(i) from the Constitution, and let parliament, not the High Court, set out the qualifications for MPs and senators in the Commonwealth Electoral Act.

Yes, other countries ban foreigners from sitting in their legislatures; but they do it in less clumsy, overwrought ways. The first draft of our Constitution in 1891, by Tasmanian attorney-general Andrew Inglis Clark, proposed only that an MP or senator must be “either a natural-born subject of the Queen, or a subject of the Queen naturalised by an Act of the Parliament” (whether it was the parliament of Britain, the Australian colonies or the future Commonwealth of Australia).

Alas, the first Constitutional Convention, in Sydney in 1891, decided this was not enough. Directed by future chief justice Sir Samuel Griffith, it agreed to ban anyone who had “taken an oath or made a declaration or acknowledgment of allegiance, adherence, or obedience to a Foreign Power, or has done any act whereby he has become a subject or citizen or entitled to the rights or privileges of a subject or citizen of a Foreign Power.”

The first part of that is clear, the second confused. Even so, Griffith’s test required the aspiring MP or senator to have made an act of loyalty to a foreign power. It disqualified only those who had declared allegiance or adopted citizenship of a foreign country — not those who had some other citizenship passed on through descent or place of birth.

That alone would have ended any challenge to the Citizenship Seven/Eleven/Seventeen or however many we end up with.

But in 1897, suspicious delegates to the second Constitutional Convention in Adelaide decided that even Griffith’s wording was too liberal. Their final version of section 44 specifies that we may elect to parliament only a person who has not been convicted of serious crimes, and who is not bankrupt, in paid government office, doing business with the Commonwealth, or “under any acknowledgment of allegiance, obedience, or adherence to a foreign power, or is a subject or a citizen or entitled to the rights or privileges of a subject or a citizen of a foreign power.”

Griffith’s activity test had been replaced by a much vaguer, more sweeping exclusion, which could create danger in the wrong hands. The High Court then became those wrong hands.

The politicians, lawyers and citizens gathered at the Constitutional Conventions of the 1890s had no doubt about their own allegiance. They were British subjects, citizens of the British Empire. They came and went between Britain and its colonies without making any distinction between them. The idea that Britain — or any of its colonies — might be regarded as a “foreign power” under section 44 would have been ludicrous in the extreme.

Australia’s first prime ministers, Edmund Barton and Alfred Deakin, were the sons of British migrants. Griffith himself was born in Wales. Chris Watson, the first Labor prime minister, was born in Chile and grew up in New Zealand. Sir George Reid, his successor, was born in Scotland, as was Andrew Fisher, who led the first substantial Labor government.

Sir Joseph Cook, who governed between Fisher’s two terms, was a migrant from Staffordshire. Billy Hughes, who succeeded Fisher, was Welsh by heritage, a Londoner by birth. He was succeeded by S.M. (later Lord) Bruce, the first of four PMs of Irish migrant parents (the others were his successor James Scullin, and Country Party leaders “Artie” Fadden and Sir John McEwen).

As far as I am aware, none of these prime ministers ever renounced their British (or Irish, or New Zealand) citizenship. Bitter and vituperative as our politics often was, no opponent ever challenged their right to sit in parliament. The test imposed by the High Court last month would have seemed to them preposterous.

The court’s fallacy, they would have pointed out, was its assumption that Britain (or New Zealand, or even Canada) was a foreign country. To them, it was not. And when they were writing the Constitution, the idea that section 44 could be used against MPs who were British subjects, whether citizens of Britain itself or of the other dominions in the British Empire of old, would have been thought too ridiculous to be taken seriously.

Australia was part of the British Empire. We were all British subjects. Even in 1969, my first passport, like that of many older Australians, was stamped: “Australian citizen. British subject.” Dual nationals? We were all dual nationals. That was part of the Australian identity.

Yes, that was another age. Australia and Britain have become separate countries, as have Canada and New Zealand. Yet, as Phillip Coorey pointed out gleefully in Saturday’s Financial Review, every single case in this crisis concerned MPs who in some way had dual citizenship with Britain, Canada or New Zealand.

Had they been brought before the High Court a century ago, Sir Samuel Griffith would have dismissed the cases against them as ridiculous, and based on a misreading of our constitutional history. Family members are not foreign powers.

The best of the document’s authors knew that the Constitution would have to be reinterpreted over time. In her superb new biography, The Enigmatic Mr Deakin, Judith Brett recounts that when he was shepherding the bill to establish the High Court through a sceptical parliament in 1903, attorney-general Alfred Deakin argued that judicial interpretation would be vital for the Constitution to adapt to changing circumstances.

But not even Deakin foresaw how sweeping its reinterpretations would be. After Griffith and Barton had passed on, newer judges decided to ignore the original purpose of the section in question, and to instead place their own interpretation on it. The most notorious example came when section 92, which decreed the end of interstate customs duties, was interpreted as banning the nationalisation of the banks — although that was clearly not its purpose.

This was claimed to be an objective, “black letter” approach to the law, but the black letters seemed to provide an outcome remarkably similar to the judge’s own subjective political preference. (If any reader has found a case in which Sir Owen Dixon found the black letter of the Constitution meant something contrary to his own political views, please let me know.)

They could get away with ignoring the original intent of the Constitution in most areas, but not in this section. It didn’t happen for a long time — between 1904 and 1987 the only cases on section 44(i) were brought by Protestant bigots claiming that Catholic MPs owed allegiance to a foreign power, the Vatican. But in 1988 a new Nuclear Disarmament Party senator, British-born Robert Wood, was challenged on the grounds that he had never taken out Australian citizenship.

No, and neither had Reid, Fisher, Hughes nor Griffith himself. Nor had Wood’s status as an unnaturalised Brit prevented him being jailed in 1972 for resisting the draft.

The claim that Britain was a “foreign power” had never been put to the court before, but a case that would have seemed ridiculous in earlier times now gave the judges their opportunity. The High Court ruled that Britain was indeed a foreign power, and stripped Wood of his seat. What its authors intended section 44(i) to mean was irrelevant.

It bore out what Deakin had foreseen: the court had effectively changed the Constitution. One may well argue that, ninety years after the Adelaide convention, relations between Britain and Australia were so changed that it had little alternative. But the precedent was now set. The judges were making new law.

The majority of the court pushed it a stage further in 1992, ruling that neither the Labor nor the Liberal candidate in the Wills by-election — migrants from Greece and Switzerland respectively — was entitled to stand, even though they had both become Australian citizens in ceremonies at which they had renounced their former allegiances. That was too little to quash their former citizenship, the court deemed.

In dissent, Sir William Deane, later governor-general, and Mary Gaudron pleaded for a more liberal reading of section 44(i). Its wording on allegiance to a foreign power, Deane argued, “involves an element of acceptance, or at least acquiescence, on the part of the relevant person.”

That was Griffith’s intention too. But the latest High Court ruling has rejected it entirely. As Australia and the world have become increasingly intermeshed, the court’s interpretation has become discordantly narrow, laying down increasingly restrictive tests as to which candidates are eligible.

No one knows how many dual citizens there are in Australia. But the 2016 Census found that roughly half the population had parents born overseas, and up to a third were born overseas themselves. The court’s interpretation could exclude anything up to half the population from standing for parliament.

Let’s not forget: every victim of the purge so far has been a passive victim, an Australian citizen who took no active steps to acquire foreign citizenship.

John Alexander’s case was as absurd as any. Alexander was born here, grew up here, and became a national tennis legend in 1977 when he led Australia to an improbable victory in the Davis Cup. But it turns out that, long before his birth, his father arrived from Britain at the age of three. On the High Court’s ruling, that disqualifies the son from parliament.

I can’t put it better than Alexander did on Saturday: “I have always believed that I am Australian and solely Australian… Australia is tired of this absurd situation. I don’t have any degrees, I have a degree in common sense and it doesn’t make any common sense.”

(Don’t get too excited about the impact of Kristina Keneally running as the Labor candidate in Bennelong. Alexander has increased his majority at every election, and won last time by almost 18,000 votes. Keneally would need a swing of 9.8 per cent to win, almost twice the 5.5 per cent swing with which Maxine McKew unseated John Howard in 2007. At Keneally’s last electoral outing, across the harbour in Heffron in 2011, when she had been premier for fifteen months, the Liberals attracted a swing of 16.5 per cent across the state, and 16.6 per cent in Keneally’s electorate. The circumstances were very different, but it doesn’t suggest she’s a great electoral asset.)

Even before the Wood case, governments had been warned about the dangerously loose wording of section 44(i), particularly for those who might have foreign citizenship conferred on them without their wish or knowledge. In 1981, the Senate committee on constitutional and legal affairs urged the Fraser government to hold a referendum to delete section 44(i) from the Constitution, and replace it with a more precise safeguard in the Electoral Act.

That proposal was subsequently endorsed at the 1983 and 1985 Constitutional Conventions, and by the 1988 report of the Constitutional Commission. But no action was taken then, or after the Wood case, or after the 1992 case following the Wills by-election. The Constitution can be, and has been, amended at referendums. It just takes bipartisanship, but in this case no one has seriously tried to achieve it.

When this crisis broke in July, after Scott Ludlam and Larissa Waters outed themselves, Malcolm Turnbull had an opportunity to show real leadership. The problem was not the Greens, it was a poorly worded section of the Constitution. Yet, as so often, Turnbull opted for short-term tactics over long-term reform, and tried to shift the blame onto the Greens rather than take on the challenge of modernising the Constitution.

Two years and two months ago, a critic of Australian politics declared:

We need a different style of leadership… a style of leadership that respects the people’s intelligence, that explains these complex issues and then sets out the course of action we believe we should take and makes a case for it. We need advocacy, not slogans. We need to respect the intelligence of the Australian people.

That was Malcolm Turnbull in September 2015, announcing that he would challenge Tony Abbott to lead the Liberal Party. His failure to provide the style of leadership he advocated has been a tragedy for himself, his party, and Australia. This week’s Newspoll suggests he is now in terminal decline.

But Labor too has played politics with the problem rather than committing itself to fixing it. If we are to fit our Constitution to the modern world then a new government will have to build bridges to the opposition to reform issues like these jointly.

Does Bill Shorten intend to lead such a government? ●