First published 13 December 2017

Here’s an apparently simple question: why have so many institutions failed so many children for so many years? By fail, we don’t mean neglecting to mark attendance rolls or enforce classroom discipline; we’re talking about failing to protect children from sexual abuse, which is close to the worst crime imaginable.

The Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse, set up in the dying days of the Gillard government, is scheduled to hand its final report to the Turnbull government this Friday. As well as scrutinising 1.2 million documents, the commission has held fifty-seven public hearings over 444 days. It has heard from 1300 witnesses, many of them offering gut-wrenching accounts of what they have endured, and its impact.

In private sessions, the commissioners have listened to testimony from almost 8000 survivors of child sexual abuse. On Thursday the commission’s chair, Justice Peter McClellan, will present a selection of these accounts, Message to Australia, to the National Library of Australia, where it will be publicly available.

To casual observers, the royal commission’s work might have seemed like an inquiry into the Catholic Church. Equally if not more disturbing, though, is the evidence of the sheer range of institutions that have failed children. As well as by institutions run by various denominations and faiths, children have been failed by governments of all political persuasions, schools both private and public, non-government welfare agencies, the judiciary, sporting bodies, the scouting movement and the Australian Defence Force.

Amid the extensive media coverage of the royal commission’s work, much attention has been paid to the testimony of individual victims of abuse. Institutional figures have been subjected to searching, sometimes searing, cross-examination by Gail Furness SC, the counsel assisting the royal commission. The news media’s abiding interest in the personal and the immediate, though, means far less attention has been paid to the structural reasons why institutions have failed to protect children, and why institutions have then ignored, deflected, doubted or even covered up revelations.

On these questions, the commission has much to offer. On its website are not just transcripts and lists of exhibits about each of the fifty-seven case studies, but also fifty-two research reports. Ranging in length from forty to 300-plus pages, they examine the causes of abuse in institutions, how to better identify it, the best examples of institutional responses and treatments for survivors, and how governments should respond.

Drawing on this research, we want to try to answer the question posed right at the beginning of the article. Before that, two caveats. First, it is important to remember that the great majority of sexual abuse of children happens not in institutions but within the family home, or in the community at the hands of relatives or family friends.

Second, sexual abuse of children is by no means a modern phenomenon — inquiries into child prostitution and incest were held in Sydney in the mid nineteenth century, for instance — but child sexual abuse has, in the words of Harvard University psychiatry professor Judith Herman, a history of “episodic amnesia.”

In her path-finding book, Trauma and Recovery, Herman writes that attention to child abuse and other psychological traumas has oscillated between periods of intense activity and periods of inertia. Why? “The conflict between the will to deny horrible events and the will to proclaim them aloud is the central dialectic of psychological trauma.” The study of psychological trauma also brings people ineluctably into contact with human vulnerability and the human capacity for evil.

Sympathising with the victims of a natural disaster is easy, but when people are responsible for the trauma, by sexually abusing a child for instance, those who bear witness are caught between victim and perpetrator. To sympathise with the victim we must take on part of the burden of their pain, and do something about it. But the perpetrator makes the opposite demand, says Herman, and he (it is overwhelmingly men who sexually abuse children) usually occupies a position of power and authority. Speaking out demands not only will but courage.

With all this in mind, we focus here on a particularly useful research report written for the royal commission by Donald Palmer in collaboration with Valerie Feldman and Gemma McKibbin. A professor in the University of California’s business school, Palmer drew on the knowledge he accrued studying the dysfunctional culture of the business organisations that contributed to the global financial crisis.

The first thing their report makes clear is how little academic attention has been given to examining why institutions fail children. A search of the academic literature yielded 4400 articles about child sexual abuse but only forty-one — or 1 per cent — looking at the role of the cultures of institutions.

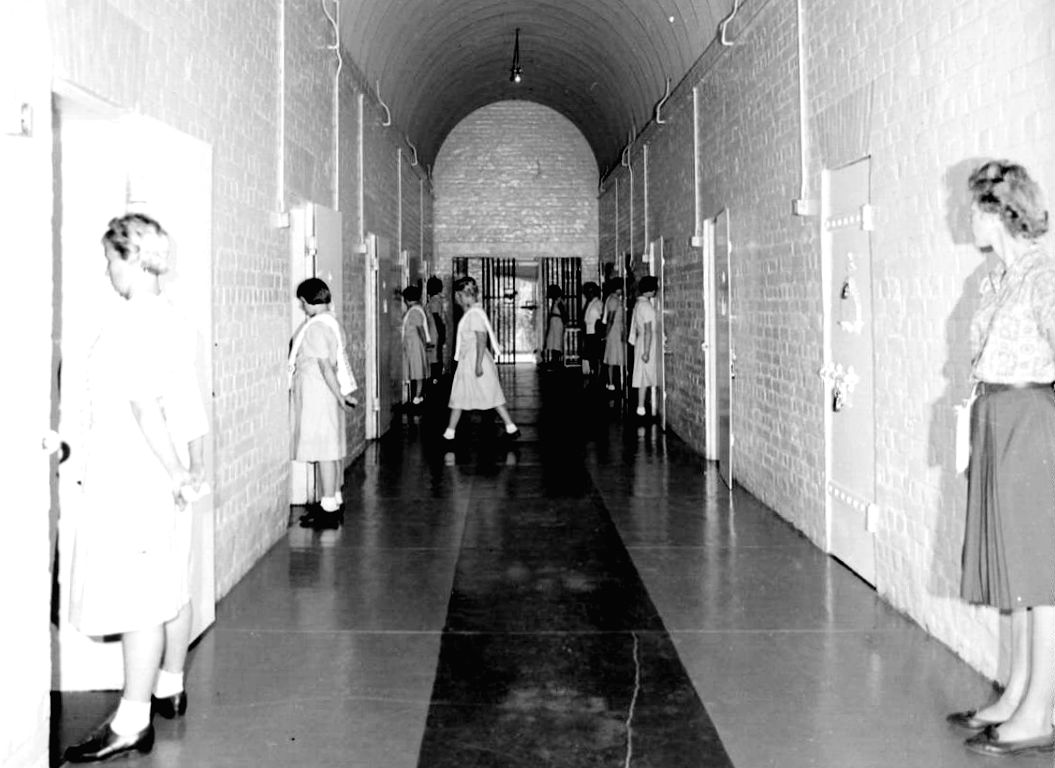

Mapping Palmer’s framework and the existing literature onto the commission’s case studies of seven institutional settings, the report found that children in institutions were sexually abused in one of two ways. They were attacked suddenly, with little prior interaction, as the commission heard was the case for inmates at the Parramatta Training School for Girls and the Institution for Girls in Hay. These attacks were easier for the perpetrators because the girls were imprisoned and subject to their absolute authority. The second type of abuse, seemingly more common in Australian institutions such as the Catholic Church, boarding schools and sporting clubs, unfolded over time, and inevitably involved grooming and secrecy. According to Gemma McKibbin, a research fellow at the University of Melbourne, “You can’t have child sexual abuse in institutions without secrecy or grooming or both.”

Unrelenting routine and hard labour: Parramatta Training School for Girls in the mid 1960s.

With most cases of child sexual abuse taking place in the home or perpetrated by people they know, though, a third approach involves a “slippery slope of boundary violations.” Researchers say this abuse is more “haphazard” than the deliberately planned attacks commonly seen in institutions. Each time a social or personal boundary between the adult and the child is transgressed, the abuser is encouraged to escalate his or her behaviour. This is not to suggest that such abusers are any less responsible for their actions. Rather, the gradual shifting of boundaries is a variety of the grooming process.

Regardless of the pathway taken, though, the research is unequivocal: perpetrators are culpable for their actions and the children are victimised in equal measure.

Within institutions, researchers found that the perpetrators are more likely to plan their abuse carefully. Integral to this planning are the special attention, privileges and gifts given to planned victims. Critically, this grooming extends to the perpetrator’s own colleagues and the child’s parents and caregivers, and is designed to shore up his or her reputation as someone to be trusted. As a consequence, victims are less likely to report the abuse and, if they do, they are less likely to be believed.

This leads to the broader question of why child sexual abuse isn’t detected by those working in institutions, for which the research identified a series of reasons.

First, institutions’ hierarchical structures mean that they compartmentalise duties, encouraging employees to focus on efficiency rather than the merits of the tasks they carry out. This, says the report, is a root cause of “organisational misconduct,” whose most infamous expression was in the defence that they were just following orders used by Nazi officers at the Nuremburg war crimes trials.

The Caringbah Outside School Hours Care program staff handbook shows how the laudable aim of creating positive relationships between staff and children can mask grooming behaviours, making it difficult for staff to identify and report abuse. “You are doing a good job,” the handbook said, “when… your children are always hanging on you, holding your hand, or asking for piggyback rides.”

Second, so insidious is grooming that the child, by accepting gifts such as drugs or alcohol, can be accused by the perpetrator and those representing the institution as being complicit.

Third, the more status and power the perpetrators and their allies have in an organisation, the harder it is for the victim and those who observe the abuse to be heard and believed. They may even be punished by both the abuser and the institution.

The effect of this power imbalance is starkly illustrated in the case of a thirteen-year-old girl who swam for the Scone Swimming Club and was coached by Stephen Roser. His position of authority obliged her to follow his instructions when he told her to “float stomach down in the water in front of him and to wrap her thighs around his hips and stroke with her arms without using her legs”. While she was in this position he sexually abused her.

Palmer’s research found at least five other hurdles to the detection of abuse.

The first is known as “motivated blindness,” the tendency we have to overlook or downplay events that might affect us badly. This could explain why so many of the royal commission’s case studies include differing accounts of the same event. For example, a mother of a Geelong Grammar boy said she told the principal that a teacher, Jonathan Harvey, had made “sexual advances” towards her son. But principal John Lewis testified that she had only “complained” that Jonathan Harvey tried to massage her son’s thigh after a rugby injury.

The second is a variation of the first; “cognitive dissonance” occurs when staff in an institution observe behaviours in workmates that are, on the face of it, disturbing but don’t square with their existing perceptions. In these instances, Palmer says, staff either dismiss the behaviour as accidental or a one-off, or they alter their own perceptions to see the behaviour as benign or insignificant.

The royal commission heard how a worker at the Caringbah Outside School Hours Care program didn’t report her suspicions about her superior, Jonathan Lord (who was convicted of having sexually abused twelve children), because she did not feel comfortable making a complaint against a supervisor, even though, “on reflection, John did sometimes have children on his lap,” as she later testified. “At the time I didn’t think it was suspicious in itself, but I did think that it wasn’t a good look, as it made it look to the other children that he had favourites.”

Third, people have a simple desire to get along in the social setting of the workplace. This desire to bond, or “in-group bias” as the researchers call it, is the key to the fourth factor stopping the reporting of child sexual abuse. It happens when members think they are better than, or even morally superior to, those outside of their group. This is particularly evident in the Catholic Church’s belief that canon law has higher standing than the laws of secular society. It also helps explain the church’s initial belief that accusations of child sexual abuse were motivated by anti-Catholic sentiment.

Fifth, the imbalance between the perpetrator’s power and status and that of the victim and those who witness the abuse means it is less likely that the institution will either stop the abuse or report the offender.

Beyond these complex social dynamics, other characteristics of what the research report terms “total institutions” work against children’s safety. By their very nature, total institutions — of which a prison is the most obvious model — involve staff exercising total control by enforcing impersonal rules and procedures. These institutions exist in order to transform human beings.

Few institutions that care for and provide services for children have all the characteristics of total institutions. But some, such as the Parramatta Training School for Girls, the Institution for Girls in Hay, and the youth training or receptions centres of Turana, Winlaton and Baltara, exhibited most of the characteristics.

Boarding schools, especially as they existed in the period examined by the royal commission, exhibit a surprising number of these characteristics. They include Geelong Grammar, perhaps the nation’s most prestigious boarding school, which is the subject of one of the case studies discussed in the research report. (One of us, a boarder there between 1966 and 1975, can recall that the toilet cubicles in the primary school boarding house had no doors and that boarding house masters were required to watch over the boys in the communal showers each morning.)

Other organisations that care for children, such as daycare centres, sporting clubs, scout groups, schools and churches, display some attributes of total institutions: they constitute “alternate moral universes” that can hold all-embracing assumptions about human nature; they attempt to extinguish their members’ previous identities; they promote secrecy; they have unique power structures; and they have unique informal group dynamics.

All of these factors are evident in the Catholic Church, an organisation premised on the belief that each human being is flawed but capable of redemption; critically, this includes priests who sexually abuse children. Church doctrine also has its own clearly defined “alternate moral universe,” in which its members are expected to follow specific rules. Fundamental to their faith is adherence to canon law above secular law.

Following these strict rules helps the Catholic Church extinguish the previous identity of its priests by assuming control of every aspect of their lives, from how they dress and where they live to the character of their intimate relationships, as prescribed by the vow of celibacy.

The upholding of canon law also explains — but does not excuse, as the royal commission has made abundantly clear in the release of five reports about the church in the past week — the church’s practice of dealing with offending priests itself rather than reporting their crimes to the police. Among many examples heard by the commission was an account of how John Gerard Nestor, a priest in the diocese of Wollongong, was moved to another parish after offending, and went on to sexually abuse more children. Parishioners were not told of the previous crimes.

But the church’s belief in its own moral universe was also indulged by the wider community, both here and overseas. As late as 2013, in twenty-two out of fifty US states, clergy were exempt from the mandatory sex abuse reporting requirements followed by teachers, social workers and healthcare professionals.

In Australia, the commission heard that the Catholic Church wasn’t alone in receiving preferential treatment. Those in charge at the Parramatta Training School for Girls and the Institution for Girls in Hay may also have been given at least de facto protection, with one survivor saying she was told by the police, “We can’t do anything… It’s a government institution and you have been made a ward of the state and they are supposed to be the ones [who look after you].”

These institutions also tried to extinguish evidence of the girls’ pre-institutional identities by shaving their heads, confiscating their belongings and banning them from speaking to guards unless spoken to. Staff, who saw themselves as transforming lives, told survivors that they would “make you or break you” and branded them “liars.” Apart from being unable to report abuse unless directly asked by a guard, this also meant the girls were highly unlikely to be believed.

Not surprisingly, the researchers found that secrecy also plays a part in child sexual abuse in organisations that don’t have the hallmarks of total institutions, such as schools, hospitals and local organisations including boys’ clubs, sporting clubs and scouts.

There is a paucity of research into these groups in Australia, but material cited in Palmer’s report showed that senior officials of Boy Scouts of America withheld from junior staff details of child sexual abuse by other staff members. Instead, they “quietly” referred abusers to counsellors to “straighten up” and then let them keep working, which, like the treatment of Catholic priests in Australia, allowed them to abuse again.

Total institutions, and institutions sharing some of their characteristics, can have very strong informal group dynamics that may influence the reporting of child sexual abuse. Managers and staff who work for organisations that don’t encourage any discussion of sex or of the problematic behaviour of co-workers may be reluctant to report their suspicions of abuse. Co-workers in these workplaces may see any criticism, however slight, as divisive.

A draft letter written by the principal of Geelong Grammar, John Lewis, intended for teacher Jonathan Harvey, demonstrates this reluctance to discuss child sexual abuse with any real frankness. It also shows the tension between trusting colleagues and looking after children in their care:

A real problem for your continuing work in the school… is that barriers of distrust have grown up between you and a good number of your senior colleagues. Without wishing to find members in that sort of situation several house masters for instance (not just from the current group) have found themselves in situations where they are torn between the trust which they would like to exhibit in a colleague and their responsibility. Their concern is over relationships with some pupils which they do not believe to be in the best interest of those pupils…

One staff member who worked with Jonathan Lord at the Caringbah Outside School Hours Care program said she would feel uncomfortable making a complaint “because although it is really good that we have lots of friendships with the team, things always seem to get back to people even if they are not meant to.”

The researchers found this impulse to trust superiors, peers or subordinates is stronger where there is a shared professional or religious affiliation. The Catholic Church has an elaborate organisational apparatus for dealing with complaints against priests, which includes the Congregation for the Clergy. This organisation is staffed by priests and known to favour fellow priests, as it did in the case of John Gerard Nestor, whose appeal was sustained, slowing his expulsion from the priesthood.

A final important contributing factor is the informal power dynamics operating among children themselves. The royal commission heard, for instance, that when a boy at Geelong Grammar was sexually abused at least some of his peers took part or did not step in to stop the abuse.

Informal power dynamics can also make it difficult for victims to report abuse. Survivors of abuse at the hands of fellow inmates in youth correctional institutions told the commission that they didn’t report the abuse because they feared retribution. It can also stop victims reporting the abuse for years, as appears to have happened with a survivor of abuse by swimming coach, Terry Buck. The victim testified he kept silent about the abuse because Buck, a fellow coach, enjoyed the status of “an Olympian and an Australian sporting icon.”

This article has only begun to sketch the complex set of interacting social, psychological and cultural elements that have allowed so many children in so many different institutions to be sexually abused. What is important to underscore is the fact that at the centre of every instance of child sexual abuse examined by the commission is a socially sanctioned imbalance of power between the child and those charged with the responsibility of looking after them.

The flood of testimony by adult survivors of abuse over the past four and a half years has revealed many things, not least an unintentionally and bitterly ironic illustration of the original problem of power imbalance. When adults testify to their abuse, they are usually believed; when children, especially those in the care of institutions, testify, they often aren’t. Yet that is when they most need to be heard because that is when they are most vulnerable. ●

By the same authors: Creating child-centred institutions