A decade and a half ago, in mid 2003, the federal government stopped doing something that governments have done continuously since 1946. It would no longer help unemployed people find jobs, and would instead give the task to a group of charities and private providers. Justifying this transition to a scheme it called Job Network, the Howard government argued that finding jobs for the unemployed wasn’t core government business. “If that’s not a core responsibility,” responded Labor’s Anthony Albanese, “then what is?”

The question is still timely. The multi-billion-dollar employment services market offers very patchy results for the hundreds of thousands of jobseekers in the system. Through Jobactive, the post-2015 version of the scheme, the federal government pays $7.3 billion over five years to sixty-five private and not-for-profit service providers to assist about 750,000 jobseekers each year in over 1700 locations. With that amount of public money, and with fifteen years in which to fine-tune the service, Jobactive should be an exemplar of how outsourced human services should work in a mature market.

But like its predecessors Job Network and Job Services Australia, Jobactive is a big, impersonal system struggling to deliver high-quality services for the individuals using it. Despite the occasional media report criticising elements of the program, it largely escapes scrutiny. It is a system, replete with grand alibis, for which none of the mutually dependent participants inside and outside government takes overall responsibility.

The Department of Jobs and Small Business will soon consider the successor to Jobactive. Simply creating Jobactive II would be a mistake and a missed opportunity: both the government and the opposition need to develop policies that put jobseekers’ livelihoods and aspirations first, and that means working out the best role for government in helping the unemployed, including learning from promising initiatives here and overseas.

Removing human services from direct government control and embedding them in competitive marketplaces was a key element of the microeconomic reforms of the 1990s. That wave of deregulation, privatisation and competition-based reform was kickstarted by Labor and intensified under the Coalition. In the process, we bade farewell to the Commonwealth Employment Service and welcomed Job Network.

Much was promised when the employment-services market was created. Government and industry saw it as a more cost-effective way of delivering social services. Private and non-government organisations, they reasoned, had better on-the-ground knowledge of the labour market and smarter ways of “activating” jobseekers. The new market would keep the long jobless queue moving by finding “real” jobs for the unemployed.

By 2015, according to an analysis I prepared with colleagues at the Centre for Policy Development, the system was operating at two speeds. For unemployed people with comparatively good skill sets and little disadvantage, the results were okay. For the disadvantaged jobseekers struggling to overcome multiple and often complex personal barriers, the outcomes were poor.

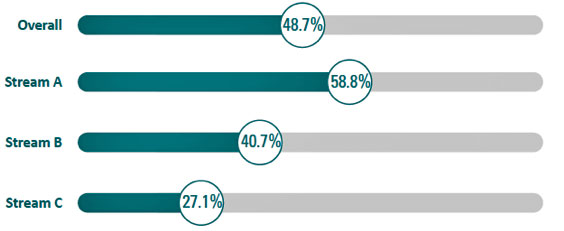

The most recent Jobactive data from the Department of Employment, which covers the twelve months to March 2017, confirms that story. Jobseekers are classified into Streams A, B or C — Stream A being those who are most employable and C being those most in need of assistance because of disadvantage. Across the three streams, 49 per cent of jobseekers are employed three months after participating in Jobactive. For the unemployed in Stream A (those with the least disadvantage), the average rate is 59 per cent; for jobseekers in Streams B and C, as the chart shows, this drops off sharply.

Employment outcomes by stream, three months after Jobactive

Source: Department of Employment, April 2016 to March 2017

Stream B jobseekers need more assistance to find a job because they lack skills or suffer from other difficulties. Stream C takes in the hardest-to-place jobseekers, including the most disadvantaged long-term unemployed, people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds, sole parents and poorly educated applicants. Only 27 per cent of people in Stream C found work in the twelve months to March 2017. Almost 44 per cent remained unemployed, and 29 per cent had left the labour force.

Where they do find work through Jobactive, it tends to be insufficient for their needs. Of the 27 per cent in Stream C who did find work, 25 per cent found a permanent role and 62 per cent found a casual, temporary or seasonal role. On average, 53 per cent of Stream C job-getters are seeking more work. The number is highest for those with part-time work, two-thirds of whom want more hours.

Why, fifteen years after the introduction of a fully outsourced system, are we left with an expensive, two-speed system? It’s no mystery: the system is not built for jobseekers, it is built for government to keep the jobless queue moving while reducing long-term welfare dependency.

The Department of Employment purchases services from for-profit and not-for-profit providers whose operations are prescribed in confidential, highly detailed contracts. Although the department has the job of monitoring service providers, poor performance is often overlooked. The loads of compliance data it collects from the providers track the behaviour of jobseekers more than the effectiveness of providers or their long-term impact on their clients.

Nor does the funding model encourage a continued investment in jobseekers. The department pays providers largely on the basis of outcomes achieved for individual jobseekers, with payments varying according to the type and length of job placement. Regional locations have higher loadings, and providers also receive payments for placing jobseekers in work-for-the-dole projects. With a focus on getting the cheapest rate per jobseeker, the department proudly claims that the 2016–17 target of $2500 per outcome was significantly outdone by the actual figure, $1453 per outcome.

Most providers rely on low margins and high turnover, focusing on easier-to-place clients while side-lining the too-hard cases despite the offer of higher incentives. This has been a longstanding problem in the system: providers are naturally looking for the most efficient way to allocate resources, and investigations have shown that some of them cut corners and rort the system. The recent collapse of one of Britain’s major public contractors, Carillion, offers a cautionary tale about misplaced faith in contracting, and the perils of focusing on costs over outcomes.

The system churns through jobseekers like customers at a fast-food cafe, with frontline staff relying mostly on standardised services and support options. Research from 2016 shows that the average caseload for surveyed staff was 147.8 clients, with each of them seeing nearly nineteen clients per day on average, either individually or in groups. Thirty-six per cent of frontline staff have no more than a TAFE qualification or vocational certificate, the research found, and almost a quarter have no post-secondary qualifications.

Among the biggest failures of the employment-services market is that different providers offer similar services, leaving jobseekers with little genuine choice. This standardisation is exacerbated by the fact that Jobactive lacks specialist service provision. When the Refugee Council of Australia examined the program’s operation in key migrant communities in August 2017, it found that refugees with no English-language skills are being incorrectly placed in Stream A, where the lowest level of support is provided. The creation of the Jobs Victoria Employment Network was partly a response to the lack of specialist federal help for vulnerable jobseekers.

Jobseekers’ negative comments about Jobactive in satisfaction surveys aren’t surprising. In the latest surveys, covering the year to March 2017, only 55 per cent of all jobseekers were “satisfied or very satisfied” with the overall quality of service. Only 38 per cent were satisfied or very satisfied with the help they received in finding a job, and 37 per cent with the help they received in gaining skills for work. A shade over half of these jobseekers didn’t believe that the service was suited to their personal circumstances. No private business would tolerate such low customer satisfaction levels, but for Jobactive agencies it is the satisfaction of government that matters.

Even though these providers deliver public services, and even though obvious problems exist, they are shielded from public scrutiny by the commercial-in-confidence provisions in their contracts with the department, which also protect them from freedom of information requests.

With a federal election looming, both major parties must come up with new, compelling answers to Albanese’s question, which lingers like Banquo’s ghost. Just what is the role of government in helping people find and keep a job? What does the government owe the citizens it serves, especially the vulnerable and disadvantaged?

Members of the public already have their own answers. In October last year the Centre for Policy Development ran an online survey designed to understand community attitudes to government. The sample was representative of community demographics. The 1025 responses collected by Essential Media included clear messages that the major parties should consider carefully.

People think that providing health, education, social security and other essential services, and ensuring shared economic prosperity, are among the most important tasks of the federal government. They think that job policies should be a major priority for the federal government. And they are deeply sceptical about outsourcing social services.

In fact, more than four out of five respondents thought it was important for the government to retain the skills and capability needed to directly deliver social services. Why? Because respondents thought government was a “better provider” of social services than charities or not-for-profits in terms of cost efficiency, accessibility, accountability and affordability for users. This wariness of outsourcing social services is deeply held: credible attitudes research from 1994, conducted by the Economic Planning Advisory Commission for prime minister Paul Keating, shows similar sentiments.

None of this is any surprise. Unemployment might be relatively low at the moment but underemployment is high. A growing number of Australians are moving into the gig economy, with its agile but insecure work. Inequality is on the rise and, faced with stagnant wage growth, people are placing a higher premium on receiving quality services. Automation and the use of artificial intelligence will change, destroy and create jobs, but our capacity to harness this disruption is nascent. If Australians genuinely believe that government has a role in the labour market and in creating shared prosperity, then it is only fair that we revise the way we provide social services.

A new strategy for reform begins with a statement of the obvious: markets alone will not produce the social gains we need. A big, standardised system churning through the unemployed and rewarding short-term placements with individual payments will not help produce a skilled, entrepreneurial, resilient workforce. Nor will it help the most disadvantaged. Government has a larger and better role to play, and some in the business community already agree.

Which leads us to how we can use public sector values and talents more effectively. Public and private capabilities should not be viewed as competing: they are essential components that should work together. Australia’s public sector remains unique in its mission and its public service values. The Department of Jobs and Small Business has a sound understanding of the labour market but could offer more services with the right re-investment in skills and capacity. It could improve accountability and transparency, and steward a system to produce results in the community interest. But its own memory of alternative service models will need strengthening; its policy and leadership capability have been run down over two decades by imposed efficiency dividends.

Promising initiatives at home and abroad offer valuable principles for improving services for jobseekers. The best way to make services personal is to make them local: a national framework for helping the unemployed will be more effective if it links to organisations that understand economic conditions in local areas, including local employers, associations and providers. Local service delivery also allows strong partnerships and networks to be built on the ground, integrating services better than market incentives ever could. Effective local programs include the Brotherhood of St Laurence’s Given the Chance scheme; with over 300 refugees having found work since 2013, it outperforms Jobactive.

It’s also important to experiment with new ways of delivering services that can scale up over time. A German program for mature-age workers has used grant-based funding and lower caseloads to invest in clients in a more personalised manner. What began as a small, voluntary program expanded organically to become an almost nationwide endeavour, with the job take-up rate moving from 26 per cent to 35 per cent over four years. Many German job centres are shared municipal and federal government facilities, showing the benefit of collaboration across levels of government.

There is no reason this could not be done in Australia. Parramatta’s Socially Sustainable Framework identifies how the city council can help with social and economic challenges, including assisting disadvantaged jobseekers. In the right mix, local intelligence combined with the resources of the federal government could work wonders. The Department of Employment could embed itself in local offices around the country, collaborating with its local government counterparts to deliver tailored services using the best service-design principles. It could start with a focus on the most disadvantaged postcodes in Australia, where unemployment is most rife.

Assistance must also be enduring. Existing services focus on the unemployed or those who have very recently lost their jobs in specific manufacturing sectors. Government should develop a national policy framework that addresses unemployment, underemployment and insecure work as a whole. In Sweden, Job Security Councils are a “continuous presence” in the labour market, helping workers through career transitions and redundancy rather than waiting for them to appear in the unemployment queue. Swedish unions and industry work in concert to create a resilient workforce that can transition through tough times.

The most effective way to reform the system is to evolve it over time. The National Disability Insurance Scheme provides a cautionary tale of the problems created when a big rollout is rushed. Pilot programs should be allowed to work quietly and calmly in target communities, helping specific groups, investing over a long period, and collecting good-quality data to compare with Jobactive. Direct involvement would make the Department of Employment a smarter purchaser of services, and improve its policy-development capacity. The department already uses pilot programs to test new services: its ParentsNext trials help parents currently out of the workforce to find jobs and education.

This evolutionary approach should lead to a comprehensive national service framework that ties together new pilots and other initiatives into a proper strategy for assisting jobseekers. One viable medium-term alternative could be greater public provision of services to the most disadvantaged jobseekers, leaving market-based providers to assist the less disadvantaged. With more trials, we’ll have more data and better options for reform.

Employment services play a pivotal role in ensuring that all Australians have fair and equitable access to economic opportunity. For too long we’ve focused services on managing the unemployment queue rather than the individuals in it. We’ll limit our own future prosperity and exacerbate social divisions if we don’t fix a service that is obviously not working. ●