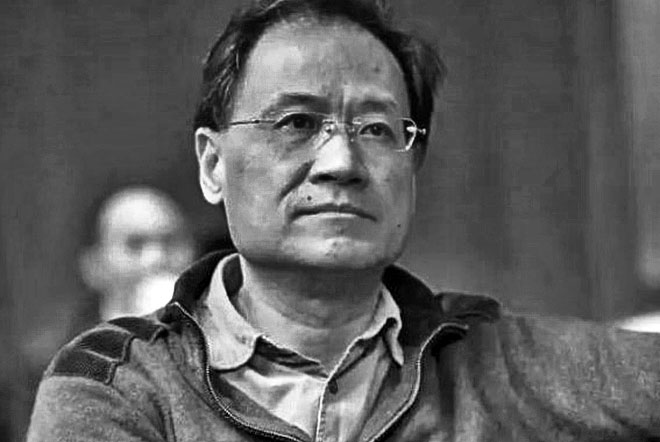

A Chinese lawyer with a higher degree from the University of Melbourne has issued a rare, powerful critique of China’s “New Era” — the period of increasing centralisation, control and personalisation of power since Xi Jingping became president. Xu Zhangrun, a law professor at Tsinghua University, one of China’s half dozen top higher-education institutions, published the powerful 10,000 character essay, “Our Dread Now, and Our Hopes,” on the website of the Unirule Institute of Economics, a liberal think tank that has challenged the return of authoritarianism.

“Yet again,” Xu writes, “people throughout China — including the entire bureaucratic class — are feeling a sense of uncertainty, a mounting anxiety both in relation to the direction the country is taking as well as in regard to their personal security. These anxieties have generated something of a nationwide panic.”

The feelings are prompted by the fact that China’s recent “national orientation” has betrayed the principles of the reform-and-opening period (1978–2008) initiated by Deng Xiaoping following the Cultural Revolution. For Xu, these principles “reflected a minimum consensus that was understood by the entire populace for the sake of peaceful co-existence.”

The stability engendered during the reform period was “not so much about This Dream or That Dream,” says Xu, in a clear reference to Xi’s “China Dream” of national rejuvenation, “it has actually been about growing the economy and developing society with an emphasis on nation building. Don’t launch any more political campaigns, let us continue to enjoy a peaceful life.”

Xu’s extraordinary essay was published while he is a visiting scholar in Japan, and it remains unclear when or whether he plans to resume his post in Beijing. Since it appeared on 24 July, it has sparked immense interest not only overseas but also, despite the country’s strict censorship, within China. The Unirule Institute, which was established during the early reform-and-opening era, had already been attacked repeatedly by the authorities and was recently evicted from its office in Beijing. Although its access to the Chinese internet was shut down last year, it continues to communicate via overseas sites.

Written in a highly literary style using traditional characters, Xu’s essay became a sensation in the Chinese-speaking world after it was republished on the website of Hong Kong–based Initium Media, which described it as “explicitly warning against the danger of the return to totalitarianism, and calling for a stop to the cult of personality and the resumption of term limits on the post of the president.” The essay, it said, “has become one of the few direct criticisms of contemporary ills in China among the intellectual class.”

Michael Dutton, a professor at both London and Tsinghua universities, says that Xu’s motivation was “probably the same thing that got him into a bit of hot water after the teachers’ hunger strike back in June 1989.” Xu has never really lost “that strong sense of justice and his role in promoting it,” Dutton tells me. “In this respect, he is a very traditional Chinese scholar who sees it as his duty to speak truth to power.”

Dutton, who describes Xu as “a very close friend,” says that the lawyer is motivated not by self-interest but by the hope of saving China by offering critical advice. “While he might hold the perspective of a traditional scholar, a lot of his views are influenced by Western legal theory. He has translated and studied a lot of Western jurisprudential texts. He has studied in Germany in his younger years and then did his PhD at Melbourne.”

Xu’s doctoral thesis focused on the scholar he admires most, Liang Shuming. For Dutton, the choice tells us much about Xu himself: “It gives you some idea of the admixture of liberalism, juridical training and traditional values that, like Liang, feed into Xu’s writings, his values, and his thinking. Xu is described as a liberal in Chinese circles, but as the influence of China’s ‘last Confucian,’ Liang Shuming, makes clear, he isn’t a straightforwardly Western liberal by any means” — though nor is he a Communist Party member.

He is largely regarded by his colleagues “with reverence and respect,” says Dutton. “Even those scholars who don’t like his views respect him. He is an incredibly charismatic teacher, utterly charming, very well read and a beautiful and poetic writer. He has, I think, come to be regarded as one of China’s foremost jurists and, within legal circles, pretty much known to all.”

A full English translation of the essay is published on the website of the New Zealand–based Wairarapa Academy of New Sinology, where it is described as a “Beijing Jeremiad.” The academy’s principal is the renowned Australian sinologist Geremie Barmé, who writes in his introduction to the essay that “Xu’s powerful plea is not a simple work of ‘dissent,’ as the term is generally understood in the sense of samizdat protest literature. Given the unease within China’s elites today, its implications are also of a different order from liberal pro-Western ‘dissident writing.’ Xu has issued a challenge from the intellectual and cultural heart of China, to the political heart of the Communist Party.”

Barmé continues: “The content and powerful literary style of Xu’s ‘remonstrance,’ as well as its tone of ‘moral outrage,’ will resonate deeply throughout the Chinese party-state system, as well as within Chinese society and among concerned citizens more broadly. If, as some scholars have previously observed, many Chinese men and women of letters revere ‘China’ as something akin to a religion — that is, an all-embracing system of identity, personal salvation, values and beliefs — then the author of this extraordinary petition, a sincere devotee, has offered his advice as an act of sacrifice on the Altar of State.”

Barmé describes Xu’s style as “a heady admix of the most dense kind of writing combining the vernacular with the literary registers of written Chinese. Despite the sometimes knotty circumlocutions, it is an incisive, amusing and sarcasm-laden work.”

For Xu, China’s reform-and-opening period was marked by respect for private property and tolerance of people’s desire to pursue wealth. “This new approach liberated the natural desires of our people to seek prosperity for themselves and their families,” he writes in the essay. “Not only did the state experience massive economic growth, it also made it possible for the state to allocate appropriate funding to science and technology, education, culture, national defence and the military.” This, he says, is the “underlying economic rationale behind why the existing political legitimacy [of the regime] has been tolerated by all-of-China. After all, this is what people regard as fundamental: touch whatever you must, just don’t touch our wallets.”

But civil society didn’t evolve in China at a similar rate. “Every time there has been an outbreak of normalcy, it has been crushed,” says Xu. “This has had a profoundly negative impact on the political maturation and individual growth of our citizenry.” Today, he writes, “people enjoy their liberties as social actors but not as citizens… In the private sphere people can enjoy limited personal freedoms, in particular in regard to normal pleasures such as eating, going about one’s daily business and personal intimacy behind closed doors…” These hopes and desires are understandable, “given the brutal monotony of the Maoist years.” But an atmosphere of insecurity is again being generated, for instance by “the forced closure and destruction of small shops, convenience stores and bars” in Beijing.

“Despite visible evidence of a certain level of social pluralism, China has experienced no substantial political reform,” says Xu, who goes on to praise the limitations on leaders’ terms in office introduced after Mao Zedong as “the only tangible example of real political reform and progress in China” over the past three decades. This year’s decision to abandon term limits on the presidency amounts to its negation. “It is feared that in one fell swoop China will be cast back to the terrifying days of Mao. And along with this constitutional revision there is the clamour surrounding the new personality cult.”

Reversing the focus on developing the economy, the party-state has revived the Mao-era slogan of “putting politics in command.” Universal dread is being felt in China’s intellectual sphere, says Xu, with a severe contraction of the publishing industry, tightening controls on the media, and new restraints on exchanges between China and the outside world.

“We are even seeing examples of official propaganda in which children are encouraged to report on their parents, in betrayal of normal human relations…” says Xu. “University lecturers have been repeatedly punished for what they say; they now live in trepidation, ever fearful that party ideological watchdogs or student spies will report them,” while local bureaucrats, “fearful of making political mistakes, are forced into passivity.”

By Xu’s account, Xi Jinping’s high-profile anti-corruption campaign hasn’t reassured ordinary Chinese. In fact, it’s seen as an augury of “a form of KGB-style control that will become embroiled in the factional politics of the Communist Party. As a result, people are panicked that we may be returning to the long-gone days of class struggle.” Memories of a political model based on constant pitiless struggle are raw, “and the concerns that it could well be reimposed on China are real.”

China’s international aid program, which is unsettling many in the West, also attracts Xu’s concern. For a developing country with a large population, many of whom still live in a pre-modern economy, such policies are born of “our Vanity Politics,” he says. Meanwhile, the way intellectuals are regarded “has long been the ruling dynasty’s most reliable political barometer; it has reflected the basic tenor of the nation’s life. The Ministry of Education has repeatedly declared that it is necessary to intensify ideological education among educators,” with academics who return after studying overseas regarded as a particular threat.

The result, he says, is that “people are being scared into silence… Without intellectual freedom and an independent spirit, what hope is there for people to explore the unknown, for the advancement of scholarship or for intellectual creativity?”

During the decade under president Hu Jintao and prime minister Wen Jiabao (to late 2012), says Xu, “it seemed as though the totalitarian was transitioning towards the authoritarian… Over the last two years, however, we have seen things moving in the opposite direction.” He believes that “people have been calling for a law that requires officials to gazette their assets for many years, without effect. As cadres and government bureaucrats scale the ladder of officialdom there is a complete lack of transparency about the personal assets that accrue to their children and their families; this is a closely guarded secret hidden deep in the party’s personnel files. Despite continued anti-corruption activities, boundless new cases of corruption are constantly being generated.”

Xu urges that “an emergency brake must be applied to the unfolding personality cult” around Xi Jinping, although he doesn’t mention him by name. “The party media is going to great lengths to create a new idol. Portraits of the leader are hoisted on high throughout the land.” But he adds, “Don’t panic yet since, although over the past two years the world has entered a mini-cycle of political adjustment, the dust has far from settled,” and says that China can “get through this period” if it returns to sustained internal reform while focusing on raising the standard of living. “We don’t need heedless antagonism,” he says. “At all costs we must not throw away the good hand that we have been dealt.”

This is made all the more difficult because, Xu says, “a crowd of the ghoulish undead nurtured on the politics of the Great Game and the Cold War have taken the stage [in the United States]… Like their opposite number here, they lack a real historical perspective, they are short-sighted and avaricious, trained in a mercantilism that favours the capitalist elite, with a personality” — Donald Trump, who he also doesn’t mention by name — “amplified by bloated self-regard and the lifetime habits of rapaciousness… coupled to heinous vulgarity” and shamelessness. “Be it in China or abroad, in the present or in the past: we’ve seen their kind before.”

One figure Xu does mention by name, here resorting to the vernacular mentioned by Geremie Barmé, is the leader of neighbouring North Korea. “Even the most commonplace international meeting organised in China involves extraordinary levels of expense… Such activities are contentless and superficial” and have nothing to do with traditional hospitality. “Even our lard-arse neighbour — Kim Jong-un, a loathsome dictator ostracised by the international community — was welcomed to Beijing with an extravagant motorcade” and served the excessively expensive “top-tier special maotai,” a distilled Chinese liquor, at the official banquet. “This gesture offended and alienated untold numbers of people in China.”

It’s a heady brew. As Barmé writes in his introduction to the essay, “One could say that Xu’s gesture is both that of conscientious objection and of martyrdom for China.” But, as Michael Dutton told me, when Xu speaks in legal circles, “people listen, and do so with reverence.” Xu himself concludes, in the style of classic fatalism, with these words: “That’s all I’ve got to say now. We’ll see what fate has in store; only heaven can judge the nation’s fortunes.” ●