Run for Your Life

By Bob Carr | Melbourne University Press | $34.99 | 304 pages

First Confession: A Sort of Memoir

By Chris Patten | Penguin Books | $22.99 | 312 pages

“All political lives, unless they are cut off in midstream at a happy juncture, end in failure, because that is the nature of politics and of human affairs.” Enoch Powell’s line about politics and failure has shifted from truism to cliché. Yet, like any good aphorism, Powell’s tells much by cutting much. It has the sharpness of a single thought.

Reverse the aphorism to see its limits: most political careers fail before they start. Many dream of politics, but few are selected, much less elected.

And that end-in-failure epitaph does scant justice to the thrills and spills along the way. The thrill of the hunt. The joy of victory. The exhilaration of power: to speak and have thousands listen; to order and make things happen. Politics can demand everything a pollie has to give, yet still give a lot back.

A legendary Canberra journalist, Alan Reid, spoke of politics as “a fever in the blood.” Quoting that line, Bob Carr muses that politicians define themselves by action, and often it’s a gamble paraded as a decision. Let the dice fly high: “You play the game, you win. You play the game, you lose. You play the game. Or as old Captain Ahab opines in Moby Dick, live in the game and die in it!”

Whale metaphors appeal to Bob Carr, the longest-serving twentieth-century premier of New South Wales who zoomed into Canberra this century for a stint as foreign minister. Carr describes his beloved Labor Party as “barnacled and bruised like the toughest old sperm whale,” yet still, “with all its scars and imperfections, the essential medium for delivering change.”

Coming at politics from the other side of the world and a different side of politics, the Tory Party grandee Chris Patten ponders politics and identity as he recounts his “odd, demanding and occasionally satisfying political life.”

Both men beat Powell’s curse. Both start their books with the thought that most political memoirs are boring, then seek to break the mould. Carr delights in reliving old fights, but with a leavening of his own foibles and failures. Patten calls his book a confession.

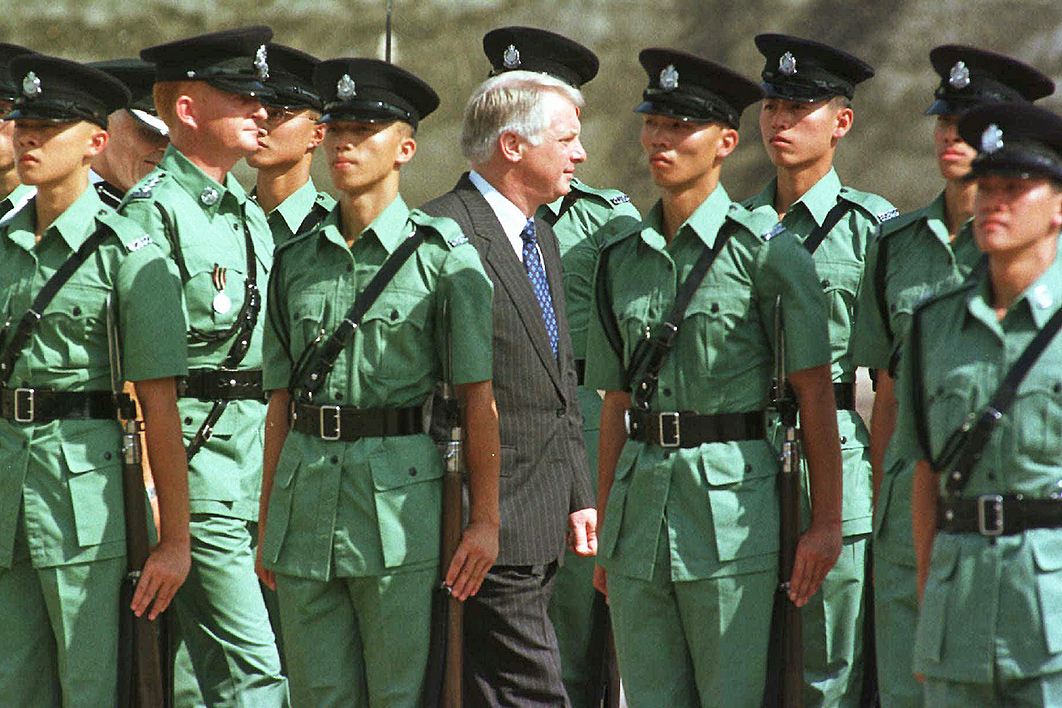

They are unusual politicians in that they’re good writers, beating the rule that those who wield power are often lousy at wielding a pen. They’ve both done the book trick several times before: Patten with his fine account of his time as the last British governor of Hong Kong, East and West, and Carr with the calculated indiscretion and sharp observation of his Diary of a Foreign Minister.

Patten offers a conventional narrative, starting with church and family. Carr does autobiography as a jazz solo: “Fracture the storyline. Start at the end. Relegate solemn, serious narrative. Hold fragments up to the light. Even flight the whole thing in the air and see where it lands…” This makes for a satisfying pairing, because the two men are trying to explain what they made of politics and what politics made of them.

Despite their party markings, they’re a rough match in philosophy and temperament. They patrol the shrinking political middle ground, pushing against the winds blowing wildly from both wings, Patten as a “wet,” Carr as a champion of the NSW Right, dedicated as much to fighting the Trots on the left as to doing battle with the Liberals on the right. As young men on the make, each was addicted to what Carr calls “the colour, drama and entertainment of America.”

Patten refracts his understandings through his experience of great institutions: the Tory Party, the Vatican, the European Union, the Chinese government, the BBC and Oxford University. Out of university, he turned down a job at the BBC and — inspired by a short stint working on a New York election campaign — followed his true calling to a job at Tory HQ (“I had found politics, or, rather, politics found me.”) Carr went from uni to the ABC, starting his trek from journalism to politics while training the distinctive voice that became such a political asset.

Patten had a classic Enoch Powell failure moment: as a key cabinet minister and the Tory Party chairman he helped run a successful campaign that saw his government re-elected; at the moment of triumph for the party, Patten lost his seat in the House of Commons.

The derailing of his parliamentary career launched him on a glittering arc as what he calls a “poobah”: the final governor of Hong Kong (1992–97), a European commissioner, and an adviser on financial management to the Vatican. He now sits in the House of Lords and, as head of Oxford University, quotes a predecessor’s wisdom that the Oxford chancellor’s impotence is assuaged by magnificence.

Patten became chairman of the BBC Trust in 2011 and reckons the stress of the Beeb job (“ten times more difficult than I ever thought it would be”) had much to do with his heart attack. His ceaseless travel as an EU commissioner had led to the reworking of an old joke at the EU headquarters in Brussels:

Q: What is the difference between Chris Patten and God?

A: God is everywhere. Chris Patten is everywhere except Brussels.

Patten gives an account of his experience in the Vatican in 2014, working with Australian cardinal George Pell on reform of the church’s finances and management. He writes that the Rome bureaucracy pushed against and weakened Pell because of his “candid and too public assessment of the quality of Italian management… I admired his intellect and thought he provided exactly the sort of heavy construction equipment that you always need to get any change in organisations where the bureaucratic cement has been setting for centuries.”

In discussing how he was shaped by politics, Bob Carr delights in the tricks of the trade and tales of battle. His account confirms an observation made by the journalist Greg Sheridan, in his “misguided youth” memoir, When We Were Young and Foolish, describing the Carr he’d known first as a fellow journalist and then as a Labor minister:

Bob was glamour in politics, but glamour arrived at through the power of will rather than natural good looks or lifestyle. By nature a short-sighted, gangling geek with thinning hair, no affinity for sport and no head for booze, he reworked himself completely, while staying true to himself, a remarkable feat. And he thoroughly mastered politics. He was as sharp with the clever one-liners as with the show-off references to history and literature.

Carr offers myriad prose portraits of the incidents and intentions of that reworking of self to grasp the chance of politics.

For Carr, Gough Whitlam is the great Labor hero — a university friend called Carr’s adoration for Whitlam and Franklin Roosevelt a “father complex.” After the disasters of the Whitlam government, though, it was NSW Labor premier Neville Wran who showed how to get things done and keep getting re-elected. Whitlam inspired Carr, but Wran was the model.

Carr quotes Wran saying that his job was to be mayor of New South Wales because “as premier you get held to account for everything that happens.” The Carr rendering of the mayoral meaning: “Your ratepayers are never wrong and they all get to vote.”

The Wran magic involved being on both sides of an argument, offering a masterclass in reconciling opposites: “He could make you a winner as he let you down.” Faced with calls to use the death penalty on gang members guilty of a dreadful crime, Wran thundered: “The death penalty would be too good for them.”

Carr observes that Wran ran his egalitarian party with a Bonapartist touch. “The ALP, like the conservative parties, is improvised and cobbled together,” he writes:

What animates and unites any ramshackle old party is clever, crafty leadership; winning speeches and punchy one-liners to lift its spirits and direct scorn at its opponents. Wran, of course, exemplifies the leadership principle; making it up as you go along if it’s done with flair.

Patten was one of the Tories whom Margaret Thatcher derided as “wets,” and he gives an account of the value of political dampness. He pushes back against doctrinaire dries (“a thick skin of prejudice, reinforced by reading the tabloids”) and embraces as his most profound political observation the thought that life is a predicament not a journey: “I am suspicious of zeal, respect institutions and historical forces, and favour consensus and cooperation where possible.”

Patten’s favourite eminent Tory is Rab Butler, a master of politics who usually found the right balance between expediency and conservative principles. Ambivalence always served Butler well, as in his telegram of apology for not attending the retirement dinner of a Tory foe: “There is no one whose farewell dinner I would rather have attended.”

Margaret Thatcher strides through Patten’s book. He offers a shrewd, affectionate but pointed critique of the leader described by Ted Heath as “that bloody woman.” He reflects that “Thatcher’s freedom from doubt helped give her rhetoric a self-confidence that frequently belied what was really happening.”

Thatcher was “a strange mixture of kindness and occasional bullying” who developed a “battling Boadicea personality and a brittle carapace of opinions on everything under the sun. In practice, she was mostly more cautious and politically smart than her language.”

Blessed with both courage and luck, Patten writes, Thatcher drained a sea of fudge and re-established the governability of Britain. In her retirement, he judges, she became more stridently right-wing than her political instincts ever allowed when in office. And the “virus of disloyalty” she injected into the Conservative Party has much to do with the Tories’ “long-running nervous breakdown” over Europe. Patten is scathing about Brexit: “We have a century of experience to prove that narrow, bigoted nationalism is the path to trouble.”

Surveying seven years as NSW opposition leader (1988–95) and ten years as premier (1995–2005), Bob Carr dances from episodes to vignettes, mixing anecdotes with analysis: a “forty-carat political stuff-up” (road tolls), beating the bastards in a multinational corporation over asbestos, ditching a minister after one candid sentence in cabinet revealed his corruption, and being a tree-hugger (creating 350 national parks) and a politician who hated sport.

He offers a tough tutorial on how to survive, even thrive, in the worst job in politics — opposition leader:

- Cement the relationship with the party machine, so that any caucus challenger risks losing preselection.

- To have a chance at two terms as opposition leader, maintain relations across caucus but don’t be one of the boys. “Leadership involves an element of distance, the dignity of distance.”

- Hunt hard, because the hunt counts. Just as feral animals are “predatory and opportunist,” oppositions must take government scalps.

- Beware the aggrieved and unloved of the electorate. For every claim or charge, demand documentary evidence. Seek to hurt the government but nurture your own credibility “as if a cache of precious metal.”

- Fight until the tide turns. Opposition leaders are a “lonely, unloved breed,” prone to pessimism and fatalism. “Your personality is corroded by the frustrations of opposition leadership. You’re failing to sell yourself against a mood of public dislike. You find the whole political process unpalatable. You even doubt the viability of your own party. Then, everything changes.”

- Master parliament. “Become obsessive about speech preparation and drive your staff to research, research, research.”

- Make explicit policies, yes, but beware the swamp of detail. John Hewson’s 1993 election defeat with his tax manifesto is “a classic example of an opposition leader throwing away the chance to be prime minister because of ‘policy specificity.’”

- Don’t overreact to the small things. “In opposition many of the things you do fall short, as you get captured by the small buffooneries of parliamentary life and the demands of the daily news cycle.”

The purpose of politics is to crawl and claw out of the desert of opposition to attain the verdant chances of power. As Carr observes, “The joy of leading a government is getting to choose its words.” Carr and Patten offer fine words on the joys of the job. You can have a good time trying both to serve and to win.

Politics is, indeed, a strange life. Anything this important must carry risks — plenty of failures to go with the wins.

To rise by the vote. To live by the vote. To fall on the vote. The fall at the end is the exclamation mark on all the votes that went before, in a political life well lived. •