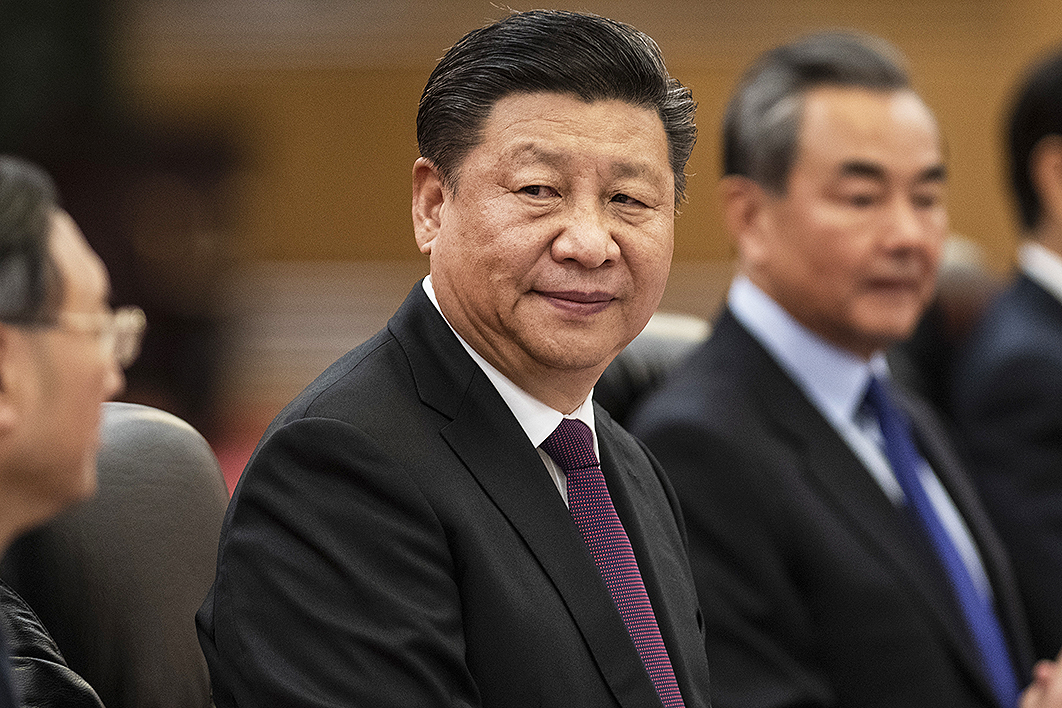

In early 2017, with the world still reeling from the unexpected election of Donald Trump as US president, China’s president Xi Jinping appeared before a World Economic Forum audience so disorientated that it was wondering whether the People’s Republic could become a counterweight to the emerging chaos. Xi spoke well. He supported the process of globalisation. He stood up for free trade. He was powerful and convincing on the need for openness. The speech got wide coverage and good press. It was one of his most impressive PR coups.

Two years later, every shred of reputational capital China gained that day has long since dissipated. Trump’s disruption of international trade had the unwitting side effect of forcing a reluctant China into a spotlight it was probably not prepared to deal with for another decade, and underlined a host of awkward issues, including the country’s internal security measures, the behaviour of its high-tech firms, and the purpose of the Belt and Road Initiative. As a result, China seems more isolated and more at odds with much of the world than ever before.

This is not a good situation to be in. The world’s second-largest economy has shown itself to be defensive, incapable of taking criticism, and often opaque and secretive in its diplomacy. During Hu Jintao’s presidency (2003–13), billions were spent on promoting China’s soft power and conveying a new image to the outside world. Today, that money seems to have been wasted. Never has the world been more in need of a constructive and positive China, and an open-minded attitude towards it. Even for those who have invested time and effort for many years in trying to explain the nuances and subtleties of its position, the last twelve months have been a searing experience.

The worsening crackdown in Xinjiang is among the most serious expressions of the problem. The government’s use of almost ubiquitous security measures to eradicate not just any political opposition, but also, much more worryingly, any expression of religious identity that worries the leadership (and that seems to cover most varieties) has been both a human and a PR catastrophe. Even the most hawkish China-watchers would have found it hard to devise this dystopian scenario. As a response to security issues — some of which have validity (sporadic attacks linked with radical Islam have been taking place in China since 2013) — these measures will almost certainly create decades of resentment and fuel the very disharmony and radicalisation they are meant to damp down.

Compounding Chinas problems are its response to the US pushback and the escalating problems over Huawei and other technology companies. Increasingly international in their operations, these companies are key targets for US displeasure over intellectual property theft and cyber-espionage. Canada’s recent detention of Huawei’s chief finance officer, Meng Wanzhou, at the request of the United States — which alleges she arranged breaches of sanctions on Iran — appears to have led to the arrest of at least two Canadian nationals in China. On the face of it, the legal process in Canada appears transparent, whereas China has imposed a near-complete blackout on its arrests: no bail, no proper indictment, and an almost comically defensive and confusing response to Western journalists’ questions.

All of this has been supplemented by crude and bullying diplomatic behaviour. During last year’s Pacific Islands Forum, at which China is merely an observer, the country’s representatives were accused of shouting down delegates in an open session, and then trying to gain access, uninvited, to the host’s office in order to change the final communiqué. Then, on New Year’s Day, President Xi issued a declaration on Taiwan that restated standard policy positions in such a threatening tone that the approval rating of Taiwan’s president, Tsai Ing-wen, rose by over 10 per cent following her measured response. The Belt and Road Initiative, meanwhile, continues to attract intensive press interest, partly because Beijing stipulates that some of its most prominent projects must be built by Chinese rather than local labour, and partly because some projects are believed to be generating unsustainable host-country debt.

Under Xi, China had an opportunity to reach out and explain what the world would look like if it played a bigger role. After a decade of the travails associated with the Brexit vote, the election of Donald Trump and the rise of populism, more people than ever were willing to listen to anything fresh that China could contribute. While there are plenty in Beijing who seem to believe that the spate of bad news stories about the country is part of a conspiracy to contain and humiliate it, that is unfair and disingenuous. Some commentators might want to see nothing but bad in China’s behaviour, but the majority are neutral, and there are also many who see positive relations and good-quality cooperation as key. China is making that constructive and moderate position increasingly difficult to advance.

It is a tragedy that China is in this position, not just for China itself but also for the rest of the world. Things need to change radically, and quickly, before the country settles into the role of outsider and becomes an object of constant suspicion and criticism — and before we all have to contemplate a future in which one of the world’s most important powers exercises influence through force and fear. •