It’s almost a decade since the Henry Review of the tax system recommended an increase in Newstart payments, with new rules designed to help them keep pace with pensions. Treasury secretary Ken Henry and his colleagues proposed that indexed “adequacy benchmarks” be introduced to make the payment system more “robust,” and that rent assistance should be lifted and linked to movements in national rents.

But the government still sees no need for change. “We have one of the best safety nets, if not the best, of anywhere in the world,” prime minister Scott Morrison declared in May. The unemployed “don’t just live on Newstart alone,” he said. “It goes up twice a year and 99 per cent of people on Newstart are also on other payments.” Meanwhile, Labor has backed away from its promise of a comprehensive review, with shadow treasurer Jim Chalmers declaring, “If people want to see a boost to Newstart, then they have to convince the government.”

How do the figures look in 2019? Single unemployed adults on Newstart receive $555.70 each fortnight, or just under $40 a day. Most of them also receive the energy supplement, a modest annual $228.80, or about 60 cents a day, which is hardly likely to significantly boost their living standards. People aged sixty or over receive the slightly higher rate of just over $600 a fortnight, and move to that higher rate after nine continuous months on Newstart. Like all low-income families, people on Newstart with children also receive family tax benefits.

If they’re renting privately, single people on Newstart are entitled to up to $137.20 each fortnight in rent assistance. To get that amount, though, their rent has to be more than $305 a fortnight, leaving them with just $26.50 a day for everything else. Higher rents don’t attract more rent assistance, and so income after housing costs can be even lower.

That assumes, of course, that you can find somewhere to rent for $305 a fortnight. An Anglicare rental affordability survey found no homes in any of Australia’s capital cities that were within the means of a single person on Newstart. To pay the lowest prevailing rate would take more than 30 per cent of a recipient’s income, which is regarded as the point at which “housing stress” sets in.

As the NSW government’s rent and sales report shows, if you were on Newstart and renting a property on the twenty-fifth percentile (in other words, cheaper than three-quarters of rental properties), you would have just $14.40 a day left over for food, clothing, transport and other bills. While nearly one in ten Newstart recipients are under twenty-five and may be able to live with their parents, most of the remaining recipients are unlikely to have that option.

Unemployed Australians have always received lower payments than age or disability pensioners. But since 1997, when the Howard government started indexing pensions to average weekly earnings but continued to index unemployment payments to the consumer price index, the gap has widened significantly. Pensioners received another boost in September 2009, following the report of the Pension Review Taskforce. One of the largest pension increases in Australian history further widened the gap between pensions and Newstart. In 1997, a single unemployed person received 92 per cent of what was paid to a single pensioner; today, that ratio is 61 per cent, amounting to a gap of roughly $360 a fortnight.

That taskforce provides a good model for assessing the adequacy of Newstart. To test whether pension rates were providing “a basic acceptable standard of living, accounting for prevailing community standards” it looked at a wide range of possible benchmarks, including average male full-time earnings, the Henderson Poverty Line or a poverty line set at a fraction of median household income (the most representative income level in the population), and some form of “budget standard.” It also compared the payments to those paid in other OECD countries.

What would the same comparisons tell us about Newstart?

Earnings benchmarks: Since 1997, payments for single unemployed people have fallen from 23.5 per cent of the average male wage to 19.3 per cent. Because unemployed people tend to have earned less when in work and because an employed person pays income tax, a more appropriate comparison is with the take-home income of someone working for the minimum wage. On that measure, Newstart has fallen from around 54 per cent in 1997 to less than 43 per cent in 2019.

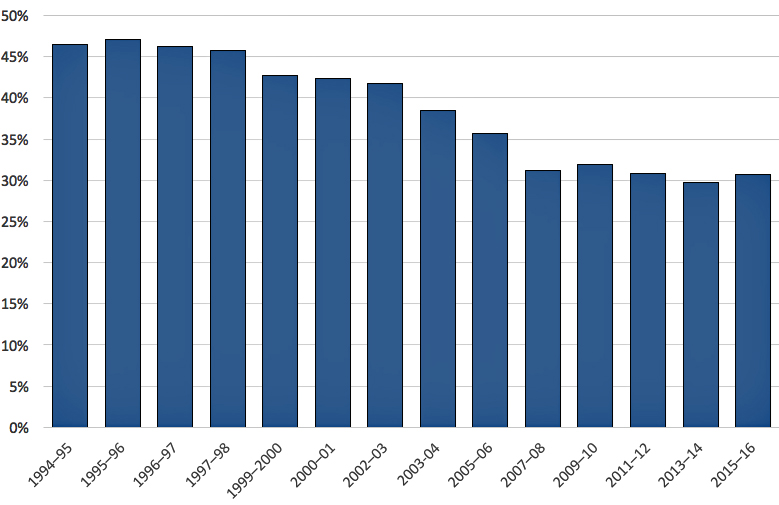

Relative poverty: Chart 1 shows the single adult payment expressed as a percentage of median household disposable income (adjusted for household size) from the mid 1990s up until 2015–16 (the most recent figures). Over that period Newstart fell from 46.5 per cent of median household income to 31 per cent — or from a little below the standard relative income poverty line to a long way below.

Chart 1: Single adult rate of Newstart as a percentage of median equivalised household disposable income, 1994–95 to 2015–16

In 1994, a single unemployed person would have received an income that was about $9 a week (in 2015–16 values) more than a person at the 10 per cent point in the distribution of all incomes. In 2015–16, he or she would have been $126 a week below that level.

Budget standards: A budget standard attempts to calculate how much income a particular family living in a particular place at a particular time needs to achieve a particular standard of living. It is derived by specifying every item needed by the family, pricing each item and adding those figures up to produce an overall budget.

In 2017, the Social Policy Research Centre at UNSW published new estimates of minimum living costs for unemployed people and low-wage workers covering five basic family types. The estimated weekly budgets for unemployed people were $434 (single person); $660 (couple); $767 (couple with one child); $940 (couple with two children); and $675 (sole parent with one child). The report found that social security payments for unemployed families are below these minimum standards in all cases, with the shortfall varying between $47 and $126 a week. “These shortfalls cast serious doubt over the adequacy of existing social safety net provisions and suggest that increased payment levels are urgently needed, especially for those in receipt of NSA [Newstart].”

But perhaps we still perform better than other countries, as Scott Morrison claims? International comparisons are complicated by the fact that most other countries use contributory insurance systems to assist unemployed people; for those who are unemployed for a short period, benefits are paid at a percentage of past earnings. These systems tend to provide higher rates of assistance during shorter periods out of work but often pay a significantly lower rate over the longer term. In Australia, unemployed people receive the same level of payment for as long as they continue to be eligible.

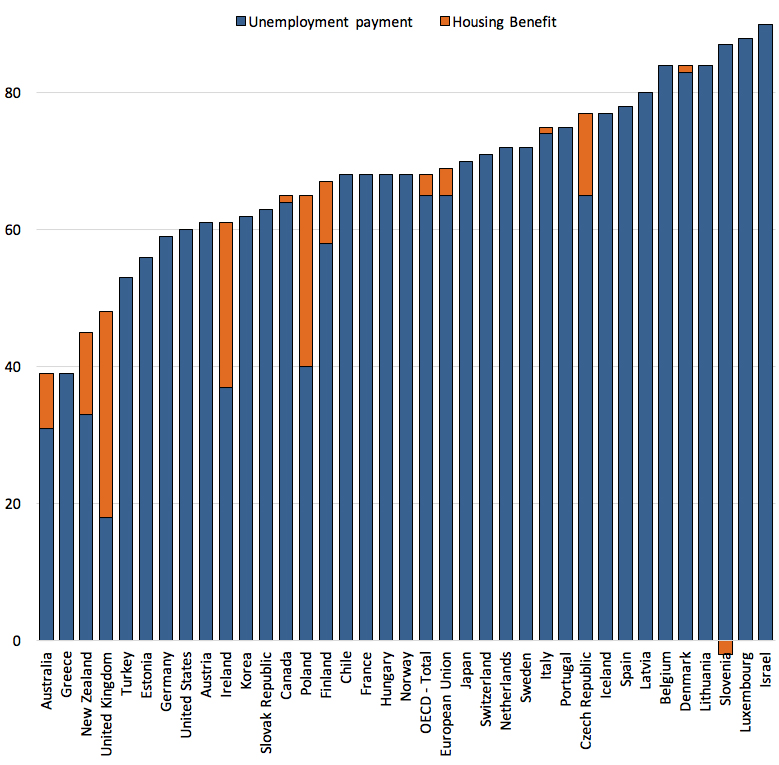

Chart 2 shows OECD estimates of the level of benefits for a single individual who had previously earned two-thirds of the average wage. If we look at the “replacement rate” — the percentage of previous earnings covered by unemployment payments — then Newstart is actually the second-lowest payment in the OECD. If we count rent assistance, then Newstart is the lowest payment in the OECD, coming in at 39 per cent of the previous net wage compared to the OECD average of 68 per cent.

Chart 2: Replacement rate of unemployment payments for a person earning 67 per cent of the average wage, 2018 or nearest year

Single person on benefits in second month of unemployment as a percentage of net wage, OECD countries

Source: Calculated from OECD data

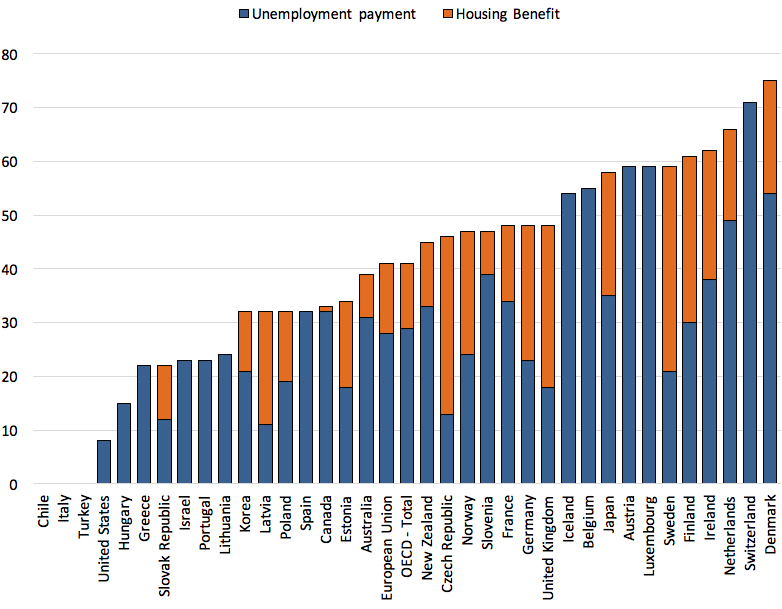

What happens if someone has been out of work much longer, say for five years? Around 150,000 of Newstart recipients, or just over 20 per cent, are still on benefits after five years. Chart 3 shows that Australia’s ranking improves considerably. Some countries provide no benefits at all for the long-term unemployed, and in the United States rates drop to negligible levels. But Australia is still below the OECD average — hardly the best safety net in the world.

Chart 3: Replacement rate of unemployment payments for long-term unemployed for a person earning 67 per cent of the average wage, 2018 or nearest year

Single person on benefits in fifth year of unemployment as a percentage of net wage, OECD countries

Source: Calculated from OECD data

What these figures show is that we need action rather than a review of Newstart. Using the same measures of adequacy used by the Pension Review Taskforce a decade ago, the case is overwhelming. And it wouldn’t just benefit people trying to live on Newstart: the governor of the Reserve Bank says that an increase in the payment would also be good for the economy.

Newstart recipients are falling into deepening poverty. The gap between Newstart and pensions, between Newstart and wages, and between Newstart and the costs of maintaining a minimum standard of living are continuing to widen. And the picture is even worse once we take account of housing benefits. For many unemployed people, Australia not only doesn’t have one of the best safety nets in the world, it has one of the worst. •