No one can say for sure who will win Canada’s election, scheduled for October, but one thing is clear. It will be a referendum on the leadership of Justin Trudeau. The polls suggest that Trudeau’s government, elected in a come-from-behind victory in 2015, has fallen behind Andrew Scheer’s Conservatives, though the margin is slight and a hung parliament possible. Four other parties are also competing for the spoils, but their prospects are uncertain.

Trudeau faces the public with a mixed record. Having assumed office in an atmosphere of giddy excitement, and having promised transparency and “sunny ways,” Trudeau has broken the hearts of those who truly expected a different form of politics. A solemn promise to change the electoral system was slowly strangled; Trudeau’s hand was slapped by the ethics commissioner for accepting free trips; a huge blow-up earlier this year saw two leading female ministers, one of them Indigenous, leave cabinet and the party as a result of Trudeau’s actions. His unfavourable ratings now surpass his once sky-high favourables.

The problems don’t end there. The government is bogged down on oil pipeline approvals, to the simultaneous outrage of industry and environmentalists. It is seemingly directionless on foreign policy. A 2015 pledge to run “modest deficits” quickly expanded into ballooning spending with no plan for a balanced budget. The Canadian House of Commons runs much as usual, with tightly controlled voting, and the prime minister’s office retains its normal supremacy. And despite promising economic statistics, polling shows many Canadians, like their peers across the Western world, are uncertain about their economic futures — a sentiment that carried Trudeau into power but is never a good sign for a sitting government.

Yet the government also has solid accomplishments. It took big steps in legalising both assisted dying and cannabis, and in enacting a national carbon pricing regime. While not delivering on other democratic reforms, it has completely overhauled Canada’s appointed Senate with a new non-partisan approach, the biggest reform of that house since Confederation. Enhanced social programs are having positive effects on poverty and income inequality. Progress on Indigenous issues remains incremental but a key step was the government’s inquiry into missing and murdered Indigenous women, which reported this year. Overall, it’s a respectable record of a pragmatic but clearly progressive bent.

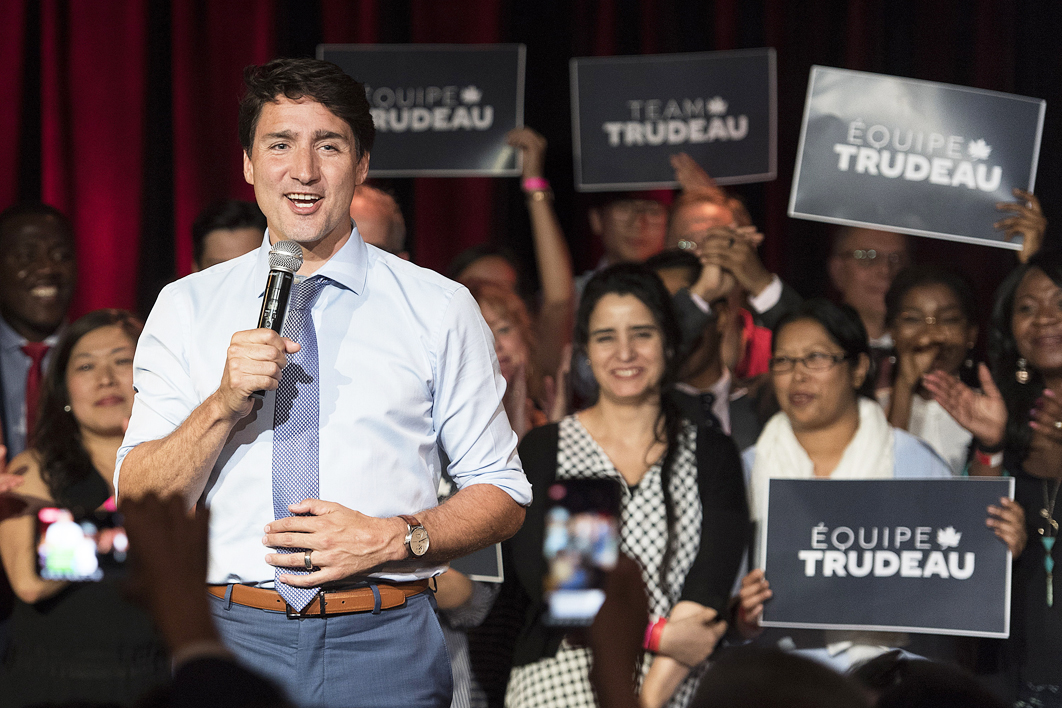

And Trudeau himself has shone as a leader, however imperfectly. Once dismissed as a lightweight unworthy of the crown, he wears it naturally (for some, too naturally). Despite missteps, his personal charm and political instincts remain formidable. And even with the disastrous start to this year, he retains the strong confidence of his party.

Though it’s hard to remember now, the Liberal Party of Canada appeared at death’s door when Trudeau took over the leadership following the disastrous 2011 election, where for the first time it fell to third place. Trudeau has restored the party’s primacy and the place of the Liberals — a dominant centrist party unique in the Anglo-American world — at the heart of Canadian politics. The looming election thus follows a historic pattern in which all Canadian elections are ultimately referendums on the Liberal Party and its current worthiness to govern, with the Conservatives waiting to take over in case the answer is negative.

The Conservatives are eager. Long led by the iron hand of Stephen Harper, prime minister from 2006 to 2015, the party lost power but still performed respectably in 2015. In post-election retrospectives, a consistent theme among Conservative operatives was regret that the party had developed too much of a nasty streak. That streak reflected Harper, a decent but disciplined individual who made it clear when he didn’t care what others thought.

The party responded by choosing as leader an individual who resembles Harper but has a sunnier disposition. Like Harper (and Scott Morrison), Andrew Scheer, a forty-year-old father of five, oozes the “neighbourhood dad.” This amiable character comfortably heads the party with its modest lead in the polls, yet he lacks excitement, and perhaps also the ruthless, calculated edge that brought Harper such success. It is unclear what the Scheer Conservatives stand for, other than opposition to the Trudeau government. It is also unclear how Scheer can increase the party’s lead, for reasons I’ll come to.

Despite its bump to second place from 2011 to 2015, the New Democratic Party, or NDP, has long been Canada’s third-placed federal party. Like other social democratic parties internationally, it is an uneasy alliance of traditional organised labour and middle-class progressives. The ongoing primacy of the centrist Liberals has pushed it to the left, leaving a narrower space for its two elements to fight over, and placing its more pragmatic provincial wings, which regularly win government, in tension with a federal party that sometimes seems uncomfortable with actual power. Until recently, the party was also torn apart by pipeline issues, with NDP governments in Alberta and British Columbia directly opposing each other.

The NDP’s permanent identity crisis is illustrated in the contrast between its past and present leaders. Former leader Thomas Mulcair, an experienced pragmatist with a strong record as a Quebec provincial minister but a somewhat abrasive image, was voted out in 2016 and subsequently replaced by the exciting but inexperienced Jagmeet Singh. A stylish former Ontario provincial legislator who has appeared in at least one fashion show, Singh embodies the diversity of Canada. Although he seemed ready to out-progressive Justin Trudeau, he has failed to demonstrate more than style, and the NDP is polling below its historic norm and well behind the major parties.

Three other parties are in the mix. The Bloc Quebecois, once a major regional force but lately plagued by leadership intricacies too complicated to discuss here, remains a marginal player but will nevertheless win some seats. More interesting is the Green Party: a perennial loser under Canada’s single-member plurality system, it has had one seat in parliament since 2008, held by leader Elizabeth May. But a by-election win earlier this year doubled the parliamentary caucus, and the party has won recent beachheads in provincial elections. It won its first seat in Ontario; now forms the official opposition in Prince Edward Island; and holds the balance of power in British Columbia’s hung parliament. This suggests a possible Green breakthrough in a handful of seats, though this is not the first time that prediction has been made.

Finally, there is something called the People’s Party, started last year by Maxime Bernier, a Quebec MP and former Harper minister who nearly beat Scheer for the Conservative leadership in 2017. The People’s Party represents a new model in Canada that is perhaps more familiar to Australians: a party driven almost entirely by the ego and ideological idiosyncrasies of one person. It polls modestly and has mostly been dismissed by observers, but could be a distraction for Scheer as he attempts to focus on Trudeau.

Which brings us back the original question of whether this election is a referendum on Justin Trudeau’s leadership. While his popularity has slid considerably, the unfavourable views of the prime minister have two very different causes. While many progressives are disillusioned, conservative voters dislike Trudeau because they feel he is too progressive. And this latter sentiment taps into a more historical vein.

In certain Canadian circles, especially among older white males in Western Canada, the very name “Trudeau” has provoked deep, primal, visceral loathing for fifty years. Something in the urbane and sophisticated image of Justin’s father, Pierre Trudeau, upset this population deeply, and the sentiment has been passed down. Though fuelled by regional tensions and the older Trudeau’s policies, it goes beyond political boundaries to a deeply personal dislike that cannot be countered by facts or persuasion, comparable only perhaps to the attitude of many Americans towards Hillary Clinton.

While he is less snobbish than his father, Justin Trudeau has inherited this ancient image of a Svengali intent on destroying normal Canada. Consequently, discourse on the political right in Canada seems at times to have descended into constant personal mockery of “Justin” and his apparently naive and misguided progressivism, often with gendered implications about his masculinity.

But while effective at rousing Conservative supporters and donors, this visceral dislike of Trudeau creates a blindness. Conservative attempts to tap into disaffected Liberal voters have largely failed because the disillusioned want a more progressive Trudeau, not less. Personalised, often superficial Conservative attacks — the glee when plastic forks were used at a Liberal event after a recent anti-plastic waste policy announcement, or Trudeau’s failure to succinctly explain his own family’s approach to waste reduction — do nothing to gain progressive supporters. The opportunity for the Conservatives to capitalise on disillusionment with Trudeau is limited, much as it was with his father. After all, Pierre Trudeau won four of five elections and even in the fifth, a minority Conservative victory, the Liberals comfortably won the popular vote.

Much of Canada still loves, or at least wants to love, the Trudeau name. Despite their human failings, both men have inspired and excited people. Justin’s good looks, enlightened masculinity, work ethic (none except inherent Trudeau-haters accuse him of laziness or poor grasp of files), inherent progressivism, and international, cosmopolitan image all combine to make a leader many Canadians are proud of. He is truly a celebrity prime minister — even in the sense that, like many celebrities, he is most inspiring and beloved when observed from a distance rather than encountered in person.

While the SNC-Lavalin affair earlier this year was a seriously off-brand misstep for Trudeau — supposed political interference in the legal system; special treatment for a Quebec firm; and overbearing men berating a female cabinet minister — the party did not take a huge hit in the polls, and Trudeau’s former top aide Gerald Butts, who resigned somewhat mysteriously in February over the affair, has returned to help oversee the election campaign. Though tarnished, the Trudeau brand holds, and the party hopes to build on this with the new platform of progressive policies it has begun to unroll, including a national pharmacare program.

The Liberal challenge is less to switch marginal voters from the Conservatives, and more to retain its own surge of supporters from 2015. As in other non-compulsory voting systems, Canadian elections revolve around “getting out the vote” — identifying supporters and encouraging them to show up on election day. In 2015 the Conservative vote remained stable, and the Trudeau victory was primarily due to a surge of new voters (and some straying New Democrats) inspired by the charismatic leader and his lofty promises, who pushed electoral turnout from 61 to 68 per cent of voters.

This year, the Conservative vote will likely stay solid; but the wave of enthusiastic Liberal voters may not, as they either stay home or turn to other smaller parties. So while optimistic that lightning could strike twice, the Liberals realise this enthusiasm is unlikely to be repeated… unless they can convince the disillusioned that a tarnished Trudeau is necessary to stop an even worse fate.

Accordingly, a key 2019 Liberal strategy is to contrast the progressive Trudeau with the Conservatives, particularly on social issues. Andrew Scheer has closely followed Stephen Harper’s lead of avoiding abortion and LGBT issues as much as possible. Yet the Liberals have taken every opportunity to try and pin Scheer’s Conservatives down, sometimes in convoluted ways; for example, noting the presence of Conservative MPs at anti-abortion rallies as proof of a hidden Conservative agenda, or pointing to Scheer’s failure to instantly support a proposed Liberal ban on “conversion therapy” of LGBTQ individuals. (Scheer said he opposed forcible conversion but would “wait and see exactly what is being contemplated.”)

Scheer is stuck, because his own backbencher record is socially conservative, as is a significant element of his party. The Conservatives can neither abandon nor fully embrace these supporters, and so Scheer follows Harper’s example of running away whenever possible from these sticky issues, with the Liberals exploiting his evasiveness. More self-inflicted restrictions by the Conservatives include taking a hard line against Trudeau’s environmental policies, particularly the national carbon-pricing scheme, and strongly supporting new oil pipeline developments, perhaps Canada’s single most divisive issue, and one that Trudeau has desperately tried to straddle. This again restricts Conservative growth, especially with Green supporters who are otherwise often politically centrist and sometimes labelled as “Tories on bicycles.”

The Liberals are assisted by the nightmare spectre of the Trump administration, though there is little resemblance between Donald Trump and Scheer in platform or style. Also unintentionally helpful to the Liberals is Ontario’s new Conservative premier, Doug Ford, brother of the late drug-smoking mayor of Toronto, Rob Ford. Catapulted to power last year in unusual circumstances, Ford is distinctly Trumpian in his tone and chaotic approach, and the federal Liberals take every chance to tie his missteps and controversies to a future Scheer government.

Scheer’s platform so far is limited and opportunistic, without a coherent vision for governing. Bernier’s People’s Party is also a distraction. Bernier has long staked his reputation as a free-market libertarian, but has increasingly also turned to nativist, anti-immigrant views that tap into a latent but very present pool of thought in the Canadian population that has been firmly kept in check by Harper and Scheer. Bernier’s eclectic party has also become a home for other social conservatives, despite his own libertarian bent. Bernier’s ego project may fizzle, but the Conservatives cannot completely ignore it.

The Liberal Party’s big tent occasionally collapses but mostly stays standing, making the party the chief alternative for supporters of all other parties. (Trudeau abandoned his electoral reform pledge when other parties opposed his preference for an alternative-vote system that might strongly favour the Liberals in perpetuity.) The party hopes it can retain and exploit this inherent appeal as everyone’s first or second choice, leading with the Trudeau brand when they can, and stampeding New Democrats and otherwise non-voters into showing up and supporting the Liberals to stop the Conservatives. Thus, while the polls are inconvenient for him at present and a Scheer government may yet come to power, Justin Trudeau cannot possibly be counted out. •