It was fifteen years ago this month, the Labor Party had just been trounced at a national election, and the ritualistic pile-on was under way. One particularly gleeful participant was a new kid on the block, a thirty-seven-year-old who many believed was destined for big things: AWU national secretary Bill Shorten.

In a Fabian Society article and accompanying interviews, Shorten explained that the “policy priorities of the Left” had “acquired a prominence that is now a barrier to Labor reconnecting with both its blue-collar base and middle Australia.” What lost Labor the election, he intoned, “was that people didn’t trust us with the economy and we didn’t seem to be talking about some of their values.”

Sound familiar? The union boss also felt that the party under opposition leader Mark Latham had “failed to establish its economic management credentials to voters in the provincial centres and outer suburbs of metropolitan Australia.” It needed to “send a clear message” that “if you have a dream to have an intact marriage, to go to church on Sunday, to have a mortgage, to want to send your kids to a private school, then the Labor Party of the inner city doesn’t look at you disdainfully.”

There was more: “Labor should reject the theory that people want services rather than tax cuts” and “avoid getting caught up in the politics of envy.” In summary, “Labor’s task now is” — wait for it — “to move to the centre.”

In 2019, of course, Shorten is being accused of committing the same crimes as Latham had, and often in the same terms. The ironies abounded back then, too, because Latham himself had launched the same missiles at his party in earlier years, in articles and talks to right-wing think tanks. Labor had drifted away from economic responsibility, he told anyone who would listen, and had been captured by “inner-city elites” and “insiders.”

Latham, who now sits in the NSW parliament for the far-right One Nation party, outlined his excuse for the 2004 election loss to Sean Kelly earlier this year in the Monthly. He had been leader for less than a year, he said, and hadn’t had time to put his personal stamp on the leadership: “The party was split, and I was stuck with [Simon] Crean’s policy framework. The party had been through a terrible period, and I thought Howard might have an election in March ’04… You just had to do the things to hold the show together.”

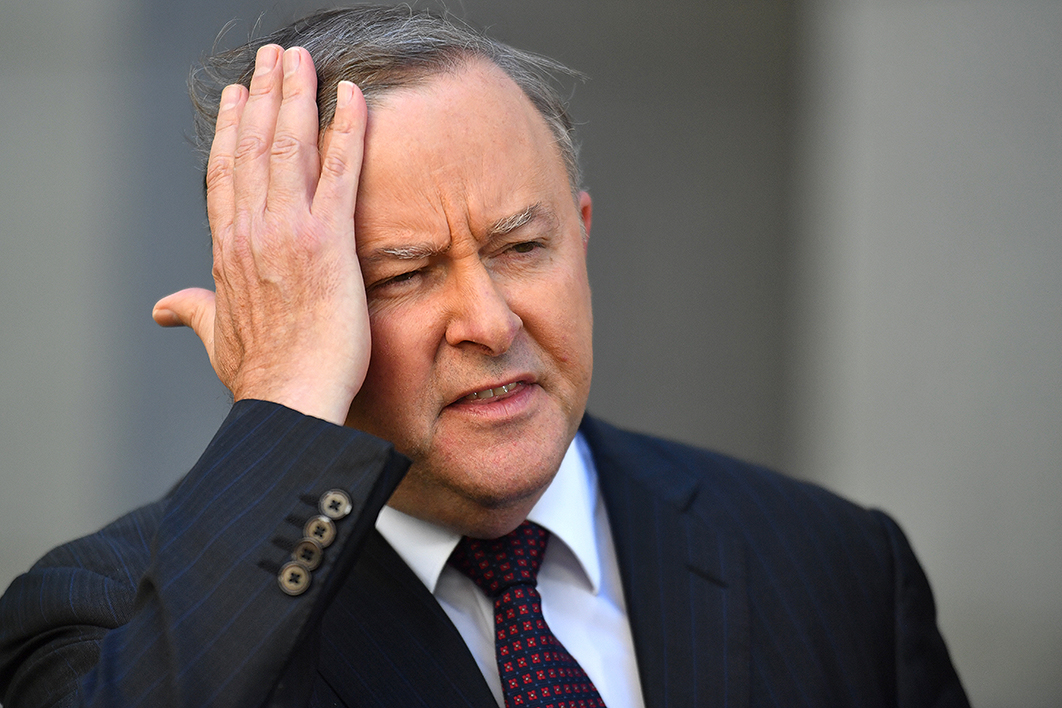

Shorten, who was leader for five and a half years, and secure in the job, can’t make the same claim. So, had he changed his mind since 2004? Were there institutional forces against which any leader is powerless? Or maybe these too-far-to-the-left, caught-up-with-trendy-issues diagnoses are just the usual lazy, puddle-deep, knee-jerk, muddled post-election ponderings from a political and commentariat class with the collective memory of a goldfish. (For a jarring illustration of this tyranny of the present, juxtapose the Australian’s Paul Kelly before and after the election.)

Shorten was saying nothing original in 2004, and neither was Latham before him; theirs has been a common theme after every federal Labor election loss going back to 1996, and possibly earlier. (An exception was 2016, when a better-than-expected result left little to regret. And yes, 1998 to a degree, when Labor romped home in the national vote but not the seats.)

So, start your engines, here we go again.

Much of the current crop of diagnoses comes, as usual, from conservative commentators — people who have no actual desire for Labor to achieve electoral success — who project their own policy preferences onto the electorate. (This is a surprisingly popular exercise among pundits of all persuasions.)

But a fair bit of the teeth-gnashing comes from inside the labour movement. Nick Dyrenfurth, executive director of the John Curtin Research Centre, is an energetic proponent of the back-to-the-working-class paradigm. As he wrote in the Sydney Morning Herald in October, “Labor must become less progressive, inner-city middle-class in structure, culture and outlook.” Dyrenfurth’s latest book, launched on Thursday, is called Getting the Blues: The Future of Australian Labor. I am yet to read it, but the title surely gives a thematic clue. (“Blue” presumably as in “blue-collar.”) He made similar points earlier this week in this interview with David Speers on Sky News.

A major party that attempted to cater exclusively to “blue-collar” voters would soon find itself a minor one, of course. There aren’t that many around any more. But (despite the catchy title) Dyrenfurth has insisted elsewhere that he means “working class” in a much wider sense.

Deputy Labor leader Richard Marles seems a convert. In a recent speech to Dyrenfurth’s think tank, in which he used the word “aspiration” no fewer than six times, he told his audience the party lost this year’s election because “at our heart we didn’t offer all Australians a root-and-branch growth and productivity agenda.” I believe the last opposition to do that was led by Dr John Hewson, in 1993. The party should hope Marles thought these were nice sentiments, not to be taken too seriously.

Marles recounted an anecdote about meeting a miner who couldn’t vote Labor because of the confused message on Adani. And, of course, he paid obligatory homage to the party in government from 1983 to 1996. “Hawke and Keating were driven by a belief that Labor should always support policies which drive productivity and growth, which reward income-earners and in turn build a society that holds aspiration as not just idealism but as a legitimate pathway open to us all.”

And there’s this: “We won’t win the next election simply relying on a big spending agenda nor running on the policies of the past in glossy brochures promising a solution to everything for everyone.”

But Richard might like to check out Hawke’s 1983 policy speech on the Australian Politics website, which he commenced with the assurance that there would be “no fistful of dollars to be snatched back after the election” before proceeding to outline a shopping list of pledges to virtually everyone. (Some were indeed snatched back after the election, courtesy of a Treasury briefing on the state of the budget. Thanks to tweep @NickDavis82 for this clip from the ABC’s Labor in Power showing Hawke mugging for the cameras at this fiscal outrage.)

This is one fundamental flaw in all the hoary Hawke and Keating schtick: it invariably calls up memories of the party in government (and fuzzy, selective memories at that) and demands that the party of today, in opposition, behave the same way. But most of the Hawke and Keating reforms to “drive productivity and growth” were enacted once they were in office, and even then the policies were rarely taken to an election first. If we really must hark back to that early time, it’s surely the 1983 campaign — not what happened afterwards — that holds the lessons.

And at the time Hawke and Keating’s governments were more progressive than the Coalition on matters such as the environment, the status of women, multiculturalism and gay rights. They too were accused of putting the environment ahead of blue-collar jobs, including by then ACTU president Simon Crean. In fact, they placed the environment at the centre of two campaigns, in 1987 and 1990. But because they won elections, it was seen as smart politics.

Today’s fetishisation of miners, a highly paid group of blue-collar workers who make up a tiny proportion of the workforce, is an exercise in nostalgia. Surely there are millions of lower-paid workers out there deserving of Labor’s attention.

And anyway, how “left-wing” and “progressive” were Labor’s 2019 campaign policies anyway?

Climate change policy is the most obvious candidate, and it’s true the opposition prioritised it more than was tactically wise. The Adani coalmine caused headaches, partly because of the threat from the Greens in inner-city electorates. In the end Labor sat on the fence, which contrasted with the government’s rushed pre-election approval. Critics presumably believe the opposition should have announced that it would let the mine go ahead. Would that have been tenable? It was a fundamentally difficult issue — all parties have them — and probably shifted some votes in Queensland. (Similarly, the 1983 battle over the Franklin Dam was disastrous for Labor in Tasmania, but it got the necessary swings everywhere else.)

Marriage equality? The survey took place two years ago. Shorten might have been wiser to follow Malcolm Turnbull’s example — support Yes but largely sit it out (if for no other reason than that hyper-associating the change with one party lessened its chances of success) — but could it really have been a turn-off for conservative, working-class Australians in 2019? If so, why not in 2016 too, when Labor’s policy was to legislate for marriage equality without a plebiscite, and the swing towards it was higher in low-income urban electorates?

(Those analyses of the 2019 result that focus on the two-party-preferred swings to the government in low-income urban electorates miss the fact that at least some of that shift was correcting for swings the other way in 2016, probably driven partly by “Mediscare.”)

The big policies on housing and franking credits — the ones that featured heavily before the poll, the objects of the Morrison government’s ferocious scare campaign — can’t be characterised as “inner city” or “progressive” by any stretch of the imagination. You could call them left-wing because they were mildly redistributive, but they were also the sort of loophole-closing that Treasury would suggest to any government of either persuasion. Shorten and Chris Bowen’s error lay in taking them to an election first.

Is it puzzling that those policies seem to have terrified exactly the people who would have benefited from them — those on low incomes? Well, that’s voting behaviour for you, more “about the vibe” and emotion than hard reality.

True, the “top end of town” rhetoric was off-putting. Why the leadership team thought it was a good idea will presumably remain one of life’s mysteries. It reeked not of inner-city cafes but an old-fashioned idea of labour versus capital.

Then there’s the unions’ Change the Rules campaign, which has remained largely unmolested in the postmortems. Promising to undo penalty rate cuts — smart or silly? ACTU secretary Sally McManus is quite a firebrand, and while the union bogeyman is not what it once was, it is never totally out of mind. To the extent that this contributed to the result, it can’t be blamed on “progressives” either.

Do “back to basics” advocates really want the party to ignore global warming and pretend the environment doesn’t matter? The answer seems to be no — just don’t go on about it so much. Anthony Albanese’s speech in Perth this week — pro-coal and recasting climate change action as a matter of new, well-paid jobs — has been lauded by some of them as a step in the right direction. Given that climate change has never been the vote-decider some analysts are convinced it is, Albo was probably wise.

Critics certainly have a point about the shrinking gene pool of Labor MPs, most evident in the over-representation of university degree holders. The Coalition is similarly afflicted, although it does seem able to preselect more “knockabout” characters, at least in marginal seats. A more varied Labor Party, containing different, colourful personas would be more appealing, so Dyrenfurth’s idea of quotas for non–degree holders is… well, interesting and worth considering.

But do people really vote for a person or party because they feel they can relate on a personal level? Do aspiring prime ministers and parties need to show they are just like voters? Or is this leadership business more complicated? Is it about making voters feel secure and looked after and, at times, making decisions that they don’t agree with at the time, like telling them to eat their greens? The electoral disaster of Julia Gillard’s “shucks I’m just the girl next door, don’t use big words, love the footy, love a barbie, not much interested in the outside world,” which so collapsed her authority in 2010, suggests that it is.

And is the get-rid-of-progressives crowd mostly concerned with policy or presentation? It’s not totally clear, but it seems mostly the latter — speaking the language of the workers, showing the party shares their “values.” By necessity they pay lip service to the greats — Keating, Hawke and Gough Whitlam — but they seem to be dreaming of a return to a time before Whitlam, a time when Labor rarely won elections.

Yes, Labor has tensions between “socially conservative” and “progressive” supporters, but the Coalition has them too — between urban economic dries, for example, and those of an interventionist bent. When a party is in opposition and lagging in the polls, its flaws are obvious for all to see. Both major parties’ primary votes have declined over the decades; chiselling down Labor’s appeal further is hardly going to help.

This brings us to a particular Dyrenfurth preoccupation, his party’s low primary vote. That, too, is a problem for the Coalition, although its vote remains higher than Labor’s, and for major parties around the democratic world. If primary votes really are the ultimate measure, Labor should be prouder of its performance in 1975, when Gough Whitlam’s government was diabolically demolished, than of Hawke’s 1990 win. And on primary votes, the Coalition’s 1983 landslide loss was better than either of its two most recent victories.

But we have preferential voting in this country, and it’s two-party-preferred support that decides elections. Much of the Labor vote has gone to the Greens, and the bulk of that comes back in preferences. If Labor really did become indistinguishable from the Coalition on issues like refugees and climate change those preferences could dry up. Fewer on the left would vote for them. Others in the middle might decide that if Labor is telling them social conservativism is the main game they might as well go for the real thing — the Coalition.

Dyrenfurth writes that “Labor supporters — especially those branding themselves ‘progressive’ — have entered a fantasy world of delusion and denial,” citing reactions to “three recent events.” The reactions he cites seem to come either from social media — quite possibly from people he, you and I have never heard of, many of whom are anonymous or Greens supporters anyway — and from climate action demonstrations. Protests are a symptom of Labor’s estrangement from the middle ground? And angry or rude left-wingers on Twitter can be conflated with “the left,” which can be conflated with “Labor”?

Similarly Victorian Labor MP Clare O’Neil, in a preview of a speech to, yes, the John Curtin Research Centre, describes how people have told her “after the election” (although not, mysteriously, before, or maybe she wasn’t listening) that they “felt that progressives were talking down to them.” It’s not clear whether she means “progressives” in the Labor Party or in the community, but if the latter she’s also setting herself and her party a monumental task to change the behaviour of hundreds of thousands of opinionated Australians.

And shadow treasurer Jim Chalmers, launching Dyrenfurth’s book on Thursday night with a speech called “Labor and the Suburbs,” accurately describes Scott Morrison’s “quiet Australians” epithet as a “slick marketing term” — and then employs it straight a further four times. Now this is a serious problem with the post-Keating party: a tendency to internalise its opponents’ preferred narratives. Chalmers also talks of Labor “shaping the middle ground,” as if that’s something a party can do from opposition.

It’s all worryingly reminiscent of that earlier, third term in opposition, when Labor so energetically inhaled the opinion-page view of “why we lost” — it was all about “values,” “aspirational voters” and the “suburbs” — that it ended up losing its collective mind. Next thing we knew, Mr Cut-through Muscle-up Suburban Man, Mark Latham, was leader.

Here’s what I reckon. Our major parties have long ago lost their raisons d’être and continue to exist thanks to institutional inertia. One day the system will fall apart, but in the meantime the old cliché is true: governments lose office, oppositions don’t really win them. Don’t overthink it. An opposition succeeds when enough people tire of the government and don’t find the alternative too risky. Creating an appealing alternative helps, but it’s not mandatory.

Getting elected is one task, governing is another. Don’t confuse the two; one step at a time.

All Labor leaders, back at least to Bill Hayden in the late 1970s, have sat in the acceptable centre ground. Shorten’s presentation was overly “left-wing” in tone, but his policy suite wasn’t radical. It was just too substantial and important to take to the ballot box.

As I’ve suggested before, Labor’s biggest mistake in 2019 was taking big economic policies to the election. If it hadn’t, it would probably be in office now and there’d be little need for soul-searching. But the big target was exacerbated by a longstanding party tic: a fear of the very mention of economics, an unwillingness to defend the party’s record when it was last in government. Shorten, like Labor leaders before him, instinctively changed the topic to health and education, as if this would induce voters to trundle off to the ballot box in a feel-good daze.

Niggling fears that the opposition would make a mess of the economy can’t be deflected; they need to be faced head on. Labor has been terrified of talking economics at least since the global financial crisis, and Shorten’s evasive persona accentuated that negative.

Marles’s speech also contained some sensible bits, like this: “[W]inning a governing majority for Labor won’t be achieved by tacking one way or another depending on the political breeze or through insincere acts of triangulation, or assembling isolated blocs of voters with a tailored message for each one.”

Fair enough. Aim squarely at that multifaceted demographic known as “Australians.” If people are ready to get rid of the government, don’t stand in their way, don’t be difficult to vote for. Don’t needlessly annoy voters. And leave the big, complicated policy announcements for when you’re in government. •