A hundred years ago, Australians were preparing for their first peacetime election in six years. Echoes of the conflict were everywhere to be heard during the campaign for what was the nation’s first “khaki election.” The date of the poll had been brought forward from 1920 in an attempt to capitalise on prime minister Billy Hughes’s successful effort to have Australia’s voice heard at the Paris peace conference. Returned service personnel were feted as members of a powerful interest group.

For all that noise, though, it was not the war that emerged as the most significant factor during the campaign but rather the arrival of a new political force that would shape the political landscape decisively over the next century.

Although the Country Party (let alone today’s Nationals) didn’t yet exist at the national level, rural political activism had been making its presence felt across the nation, including in Western Australia, where the first Country Party had been formed in 1913. The anticipated arrival of a new rural party on the national scene had even forced a change in the electoral laws, replacing the first-past-the-post system with preferential voting.

Mounting dissatisfaction with the city-oriented Nationalists (the product of a merger between the Liberals and the Free Traders in 1909) had led farmers’ organisations to run their own candidates in rural seats, splitting the conservative vote. In October 1918, a by-election in the Western Australian seat of Swan was won by a Labor candidate polling just a third of the vote after the Nationalist candidate lost support to a candidate from the Country Party of Western Australia. Two months later, a by-election in the Victorian seat of Corangamite — the first to be held under preferential voting — saw victory go to a candidate representing the Victorian Farmers’ Union, but only because of preferences from the Nationalist candidate.

When electors cast their (still voluntary) vote on 13 December 1919, candidates endorsed by various state-based farmers’ organisations managed to win just over 6 per cent of the vote and a total of ten seats out of seventy-five, all at the expense of the Nationalists. These groups included the Victorian Farmers’ Union, the Farmers and Settlers’ Association of New South Wales, the Primary Producers’ Union (Queensland) and the Farmers and Settlers’ Association (South Australia). Several candidates in New South Wales were cross-endorsed by the Nationalists and the Farmers and Settlers, and country-aligned candidates also polled strongly in Tasmania.

Exactly where and when the idea of a Country Party originated remains a matter of historical debate. A group of rural MPs had emerged in the colonial parliaments in the run-up to Federation in the late 1890s, especially in Victoria. Nominally Liberals in that pre-party era, they took issue with the proposed terms of Federation, which they saw as inimical to rural interests. Among their worries was the vexed issue of tariffs, which they saw as a burden on farmers. They also opposed the plan for the Senate to be elected using a single statewide electorate, arguing that it would disadvantage country candidates. They began, quite informally, to refer to themselves as the Country Party.

In late 1900, the Melbourne Age took issue with several conservative members who were actively working for the formation of a Country Party, which it saw as unnecessarily divisive. “We are, indeed, living in a period when nearly everyone of progressive ideas interprets the development of the colony to mean the placing of a larger and more prosperous population in the rural districts,” said the paper:

Because of this, every enlightened member of Parliament may be said to belong to the Country party. The whole House is the Country party, and any move which would set the country members and the city members working on antagonistic or different lines would only be making the Country party smaller.

The most prominent among the group of MPs was Allan McLean, who had represented a rural electorate in the Victorian parliament since 1880, briefly become premier in 1899–90, and then turned to federal politics. McLean won the seat of Gippsland in 1901 and served as, in effect, co–prime minister with George Reid in the nation’s first coalition government in 1904–05. Before his defeat in 1906 he held the key portfolio of customs in that curious government of free traders and protectionists. Although he is little remembered, McLean can be seen as a progenitor of the Country Party.

Another attempt to unite country interests came in 1913, largely at the instigation of the Farmers and Settlers’ Association of New South Wales. It was met not just with suspicion but also with hostility in some rural quarters. After a meeting had been arranged in Sydney by the editor of the association’s newspaper, Harry Stephens, the Richmond River Herald and Northern Districts Advertiser dismissed the planned organisation as “an alleged Country Party” and “merely a city newspaper party” designed to woo country voters in support of city interests.

The Herald feared a split in the non-Labor vote. “Recent federal election returns demonstrated very clearly that in and around the city Labor is solid, and that all other political persuasions must look to the country voter for support,” said the paper, “but the country voter must not be deemed so stupid that he will vote for anything calling itself Country Party.”

The tide began to turn after the war, with the movement gaining momentum from the win in the Corangamite by-election in 1918. And then came the ten seats won by rural interests in December 1919.

Two years later, the national Country Party formally came into being. The new party was led by the eccentric former newspaper editor William McWilliams, a former member of the pre-Federation Tasmanian parliament who had been elected to federal parliament in 1903. A free trader, he had advocated strongly on behalf of farmers and investigated the possibility of introducing sugar beet farming into Tasmania.

In his first speech as leader, McWilliams set out the principles of the new party. “We crave no alliance, we spurn no support,” he declared, “but we intend drastic action to secure closer attention to the needs of primary producers.” But he didn’t always feel obliged to vote with the party he led, and in April 1921 he was deposed as party leader in favour of Earle Page, a surgeon from rural New South Wales.

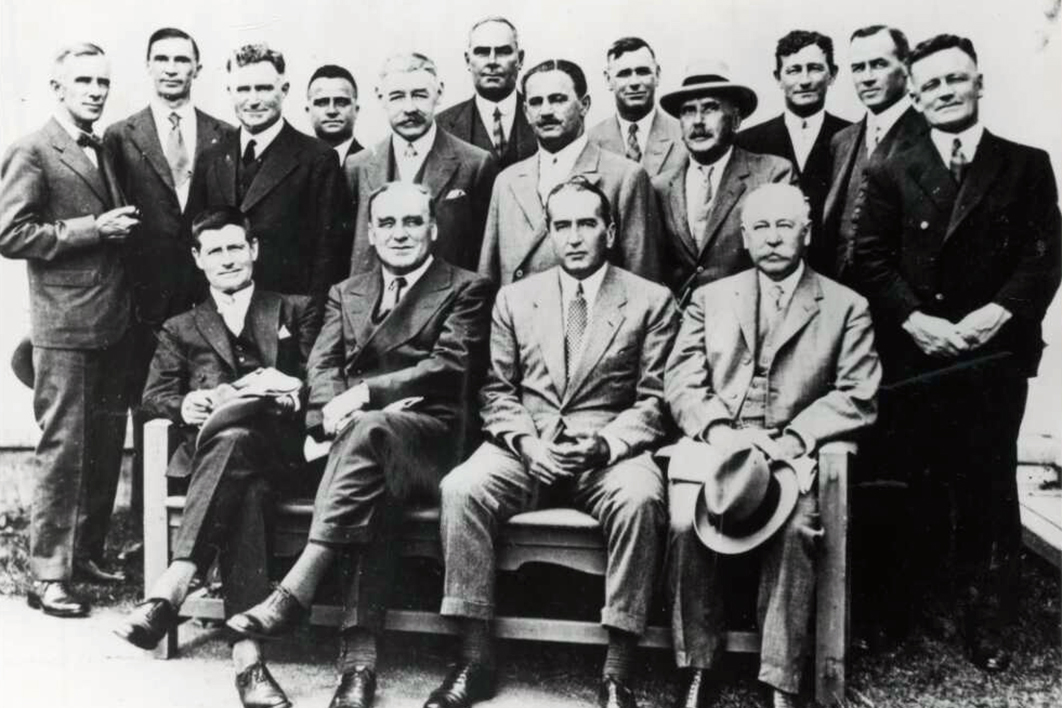

Under the leadership of Page, a ruthless political operator, the Country Party fought its first election as a united party in 1922. Winning 12.6 per cent of the vote, it found itself holding the balance of power in the lower house. Its price for supporting the Nationalists was the removal of Billy Hughes, a former Labor man, as prime minister.

In coalition negotiations with the Nationalists’ new leader, Stanley Bruce, Page demanded five seats for his Country Party in a cabinet of eleven, including the Treasury portfolio and the second ranking in the ministry for himself. Given the party held just fourteen seats to the Nationalists’ twenty-seven in a house of seventy-five, the demand was audacious, but Bruce could find no other way to retain power. He not only agreed but also accorded the Country Party leader equal status after Page insisted the government be known as the Bruce–Page government.

Thus began the tradition of the Country Party leader ranking second in Coalition cabinets, a situation that obtains right up to the present day — as does the game of political hardball initiated by Page. •