Labor’s much-reported election review, already mentioned on these pages by Paul Rodan, Rod Tiffen and me, is thankfully free of the cherrypicking that characterises much of the analysis of May’s events. Its authors don’t simply choose an electorate that dramatically illustrates their preferred narrative, and ignore the ones that don’t.

But a fallacy underpins much of the report, one that it shares with most 2019 election takes, and it has to do with swings. The biggest electoral narrative to emerge from six months ago is that booths and electorates in low-income urban Australia swung to the Coalition, while high-income ones went the other way. (I refer to booths and seats to avoid being accused of committing the ecological fallacy, but, just between you and me and these parentheses, I believe it’s reasonable to infer low- and high-income voting behaviour from these aggregates.)

These swings have facilitated a lot of drama along the lines of “OMG, Labor lost its base/blue-collar voters/the working class!”

The problem lies in taking those numbers in isolation. A swing is just the vote at the latest election minus that at the previous election. And in this case the previous one, 2016, exhibited some aberrant movements, including outsized shifts to Labor in low-income urban electorates. “Mediscare” must have at least contributed, and perhaps attitudes to prime minister Malcolm Turnbull as well.

Of course, no election result represents the natural or neutral position from which a swing should be judged. Perhaps 2016 itself was in some way correcting for 2013? So it makes sense to examine the longer term.

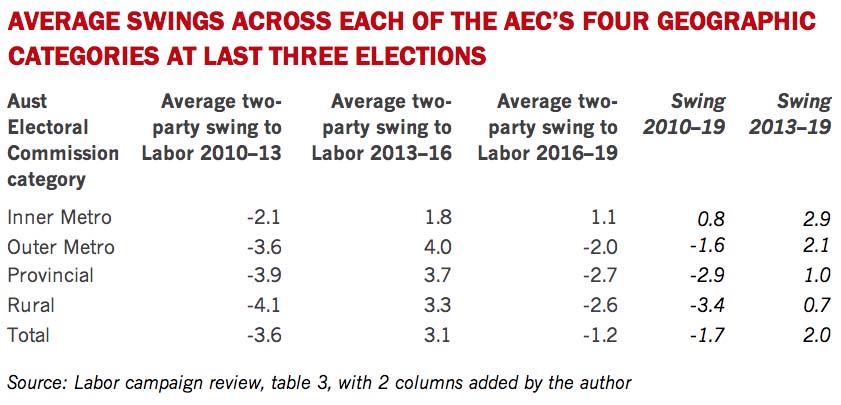

Labor’s review has a semi-bash at this in its third table, calculating average swings across each of the Australian Electoral Commission’s four geographic categories at the last three elections. But it doesn’t take the obvious next step of adding those together to produce cumulative swings over that period. I’ve reproduced its table here, and added two more columns on the right. You can see they flatten out the trend — “outer metro” in particular is pretty much the same as the national number in both long-term columns — but they do show that the further voters get from the capital-city CBDs the bigger their relative swing to the Coalition. Then again, Queensland, the least urban mainland state, would account for much of that.

Cramming all 151 electorates into one of four groups is a crude exercise. As an alternative I’ve taken a thirty-six-year look at a part of the country that receives disproportionate commentariat attention, Western Sydney. In Sydney as a whole, the aforementioned 2019 swing patterns were particularly pronounced: Liberal seats, most of which sit on the north shore, swung to Labor on average, while lower-income Western Sydney seats swung to the Coalition. In this way, swing-wise, Sydney was a microcosm of the country.

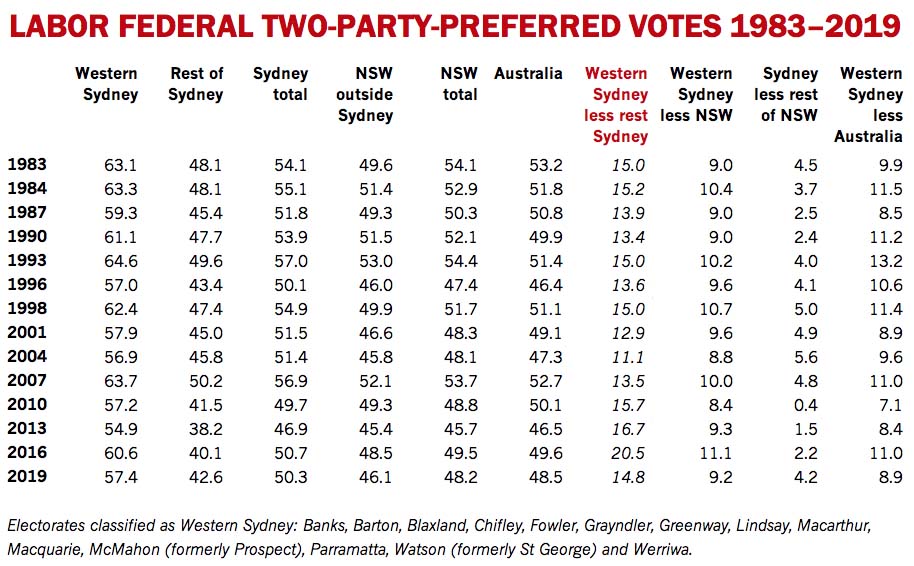

The table shows average two-party-preferred votes at each election from 1983 across Western Sydney, across the rest of Sydney, and for New South Wales and Australia as a whole. (The electorates classified as Western Sydney are listed under the table. Readers might quibble about one or two inclusions or exclusions, but it makes little difference to the data.)

The most important column for our purposes is Western Sydney versus the rest of the city, which unsurprisingly is still strongly Labor. It’s true that May 2019 saw a dramatic closing of the gap, to just 14.8 per cent. But that was off a very high 2016 figure, the largest across this time frame, of 20.5 per cent. So the 2019 swings were in part simply a reversion to the norm.

But it wasn’t just that. Were there one-offs in 2019? Labor’s big policy suite, in particular the “retiree tax” and the fictional “death tax,” along with Bill Shorten’s evasive persona provided a big canvas on which its opponents were able to aggravate doubts about the party’s economic competence.

If there is a long-term trend in this table, it actually seems to be towards greater relative Labor support in Western Sydney, before a reversal this year.

This is in the larger context of New South Wales moving towards the Coalition over the decades (making it no longer the “Labor state,” if it ever was) and movements the other way in Victoria and South Australia.

Note that the smallest gap was in 2004, under the leadership of Mark Latham,whose raison d’être largely rested on “reconnecting” with Western Sydney (and other “battler/aspirational” areas). He was from that part of the world, after all, spoke their lingo, understood their needs. Yet the effect on election day was the very opposite to what had been imagined. Citizens of that part of the country turned out to be less interested in all the “values” guff than things like economic security.

And Latham was a big target, not so much for his policies as for his persona, and self-consciously a “conviction politician” in the John Howard mould — a terrifying characteristic in an opposition leader.

Just like this year, the election before that, in 2001, had seen big swings to the Coalition government in Western Sydney, also off a high base, in this case the 1998 GST election. Again like this year, the result set off copious amounts of Labor handwringing and commentator pontificating about losing the blue-collar workers, on the issue of asylum seekers but also on “values” more generally. This neurosis culminated in the disastrous December 2003 caucus vote that gave Latham the leadership.

And so, in 2019, here we go again. Sections of the Labor Party, and much of the media, are urging the party to recapture the working class, dialling up the melodrama about the split between “progressive” and more socially conservative Labor supporters, as if the party has not always had these pressure points (particularly from the late 1960s, when it became electable for the first time in a decade and a half), as if major parties around the world — including our own Liberals — don’t have them every bit as much. (What do Liberal voters in North Sydney have in common with those in Farrer?)

So Labor’s review, naturally, prioritises “reconnecting” with “low-income voters in the outer suburbs and regions,” with “people of faith” and, of course, with “Queenslanders.”

But as we saw fifteen years ago, chasing after this or that demographic is a recipe for malfunction.

How about “reconnecting” with “Australians” instead? A rising tide lifts all boats, after all. •