At Finniss Springs, a resource-rich patch of desert country south of Lake Eyre, Arabunna descendant Reg Dodd and long-time friend and collaborator Malcolm McKinnon explore an unusual cross-cultural history. Their book, Talking Sideways, is a collaborative yarn about country, community and culture. For the Arabunna and for many other Aboriginal people, Finniss Springs has been a homeland and a refuge. It has also been, at different times and in various ways, a cattle station, an Aboriginal mission, a battlefield, a place of learning and a living museum.

Reg Dodd: A blackfella in a tartan cap

We were always classified as Aboriginal people, even if we had just a speckled ink spot of Aboriginal blood. It didn’t matter if we had dark skin, like some of my family, or if we looked more like a whitefella. That’s just how it was in those days when I grew up. We grew up knowing we were blackfellas, and we didn’t have any choice about that.

I always say I have a foot in each camp. I’m an Arabunna person and I also have Scottish blood, and I’m proud of both, because what happened here at Finniss Springs with my Scottish grandfather and my Arabunna granny was pretty unique. The outcomes of that relationship were beneficial not just to my immediate family but also to many other Arabunna and to a lot of other Aboriginal people too — Dieri, Kokotha, Antakarinja, Adynyamathanha or Arrernte. Even people from down in the Riverland or over west on the Nullarbor — there are people from those areas who have a link to Finniss Springs as well.

For me, Finniss Springs is home. I was born here. I’ve lived in this country all my life and I’ve never left here. I have a traditional connection to Arabunna country through my mother and grandmother, but Finniss Springs was also a pastoral property that was set up by my grandfather, Francis Dunbar Warren, who was of Scottish descent. My grandfather bought this property when he sold his share of Anna Creek station, up the track a bit northwest of here, right in the heart of Arabunna country. He’d taken up with my grandmother, Nora Beralda, who was a full-blood Arabunna woman. They had a family and then they came down here in 1918. My mum, Amy, told me that she was carrying her younger brother, my Uncle Angus, on her back when they came down here from Anna Creek.

The relationship between my grandfather’s family and the Arabunna people at Anna Creek was very unusual, especially in that my grandfather married an Arabunna woman and then stayed with her and his family in this area for the rest of his life. He’s buried here at Finniss Springs — he didn’t want to be buried down south with the rest of his European family.

I know plenty of other white people who had kids with Aboriginal women but they kept it as quiet as possible. They wouldn’t openly support that family because they would have been branded “nigger-lovers.” It would take a very brave man with a strong sense of right and wrong to be able to do that. There were many kids all around the country with Aboriginal mothers and white fathers, but their fathers never acknowledged those kids or took any responsibility for them. And so my grandfather was unusually humane, in that he supported his family all along and he was determined always to stay with his Arabunna family.

Grandfather’s relationship with the Arabunna people was a two-way thing. He helped the Arabunna people understand the white man’s ways, and told them what they had to do to get along. At the same time, he took advice from senior Arabunna people about the things that he needed to understand in order to live and work in Arabunna country. In his journals Grandfather sometimes wrote in Arabunna language, especially if he was referring to birds and animals or to certain places. I remember him writing about how, up at Anna Creek, all the crabholes were full after the rains and there were a lot of kudnatyilti running around — that was those water-hens. So he used Arabunna language in that way.

There was an incident out at Parker’s Well, what we call Kuthampulyuru, which means “muddy water.” This old Arabunna fellow was out there minding the sheep but then the windmill broke down. The old bloke rode back in to Anna Creek and went to see Grandfather. He kept on saying, “Kutha thakali punthaka!” — meaning that stick or spear that comes down and hits the water — but Grandfather didn’t know what he meant. Eventually, Grandfather went and got another old fellow to come over to find out what was wrong. He translated what the first old bloke was saying, and they worked out that the pump rod had broken on the windmill. So then Grandfather understood what the old bloke was telling him, and they could go out there and fix the problem. That was the kind of relationship that my grandfather had with some of those old Aboriginal people.

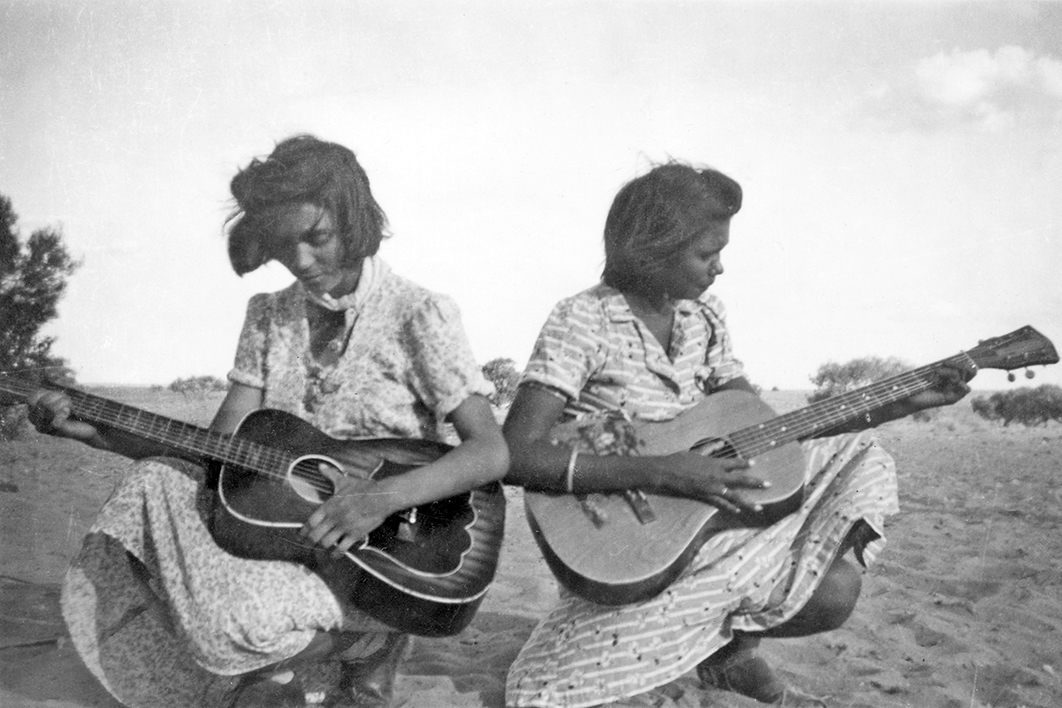

Grandfather wanted to set up a home for his own family and he wanted his children to be able to have an education. They first approached the government about setting up a school here at Finniss but, in the end, it was the missionaries who were willing to come out here to educate the kids. In 1939, the year before I was born, they set up the first school out here in an old army tent. So this is where we grew up and where we were educated. Finniss Springs became a refuge for the Arabunna and for other Aboriginal people. The kids could go to school. Families could camp here. And there was always work to be done on the station, mainly looking after the cattle and sheep.

My grandmother was a proper tribal woman, and traditionally she had a high status among the Arabunna people through her connection to certain important stories. Beralda means “the moon,” and she was known as “little moon” — parala kupa in Arabunna language — and my great-grandmother was parala parnda, meaning “big moon.” Their stories also relate to the fire — thirka in Arabunna language. When we were born we had to be placed on the thirka — that warm hearth beside the fire — because we were the thirka family mob.

There’s another story I know through my mother’s line, about these old women who were travelling and they were carrying the moon — the parala. They travelled for a long time and they were holding each other’s hands up, but then, eventually, the moon became too heavy and they became very tired. So they put the moon down, and that’s how the moon sets at the end of every night. But the other meaning of this story is that it shows how, eventually, everybody has to die. If they could have carried the moon forever, so that it never had to set, then they would have lived forever too. But the moon was too heavy and so they collapsed and died. And from that time, this is what happens to all of us.

It’s all connected, like the way that the moon controls the tides, and like the way there is women’s business that’s also affected by the moon. These stories have powerful meanings; for us, they’re connected with particular sites and places across the country. And they go back thousands of years, being handed down from generation to generation.

The knowledge that gets transferred through different generations of our people is passed on in what might seem like a casual kind of way. No one tells you to sit down and listen, like when you’re at school or something. Usually it’s just an aside, or maybe it’s something told in a storytelling form. Sometimes a story has a message that isn’t immediately obvious, but you work things out — like a jigsaw puzzle where you’re putting the pieces together in your mind. You get that knowledge over time because you’re chosen to receive it. And you have to prove you’re worthy of receiving that information. This is the way it is with us mob: we don’t talk directly. I’m like that with my family. The ones of my generation, we were brought up so that we talk kind of sideways, because that’s the respectful way.

Malcolm McKinnon: The belly of a horse

It’s amazing how much water a thirsty horse can consume, just like that. I know this from close-range experience, from the perspective of a cattle trough in which I was lounging one scorching November afternoon. My girlfriend and I had fixed up the trough so it no longer leaked, and we’d cleaned out the algae and the dead galahs and the bird shit. Wearing nothing but wide-brimmed hats with flyscreens attached, we’d spend long sessions reclining and reading books in the trough when it was just too hot to be anywhere else.

The brumbies used to come by regularly, to drink water from the leaking bore on the other side of the old railway line at Alberrie Creek, the main railway siding on Finniss Springs. Initially they stood their distance, smelling the water in the trough. When they could wait no longer they ambled up to the end of the trough, not far from my submerged feet and, two at a time, wetted their noses. The cattle trough was filled from the leaking bore, with inflow regulated by a copper float valve. I can testify that a few horses can empty a cattle trough in just a few minutes, and the float valve had no hope of keeping up. The belly of a horse is an enormous, expansive receptacle.

There’s a revealing episode in the journals of the explorer and surveyor John McDouall Stuart, recorded as he traipsed through Arabunna and Kuyani country on the return leg of his 1859 expedition to Central Australia. Stuart initiates contact with a small group of Aboriginal people and makes a gift of a pipe and some tobacco. In exchange, he asks to be taken to the nearest drinkable water. Expecting to be guided to some springs, Stuart and his party were disappointed to be led only to a deep rock hole filled with rainwater. The local people, Stuart wrote, “were quite surprised to see our horses drink all [the water].” They would go no further with us, nor show us any more, and, in a short time after, left us.’

There’s an obvious etiquette being enacted within this encounter, and a spectacular failure of manners on the part of Stuart and his companions. It’s one of those encounters where, for Aboriginal people, a warning must have sounded loud and clear. Survival in this dry country requires the maintenance of a delicate equilibrium. The arrival of the white men with their large, thirsty, hard-hooved animals would irrevocably upset the balance.

At Finniss Springs there are complexes of artesian mound springs where dense scatters of ancient stone tools lie across the adjacent sandhills, directly alongside the crumbling and splintering ruins of pastoral buildings and the newer survey pegs and concrete-encased bores drilled by mining companies. At the right time of year, with the right weather conditions, it’s possible to sit quietly in these sandhills and watch the intricate mating dance of a pair of brolgas. The tall, elegant birds dance footprints into sand moistened by water that has taken almost a million years to traverse the Great Artesian Basin, before it percolates up through these springs.

In this certain light, you might readily entertain the illusion of a pristine desert wilderness. In reality, though, this place is an industrial zone, with relics and artefacts from past and current enterprises scattered liberally throughout the landscape. There are embankments and bridges from the old Ghan railway line; there’s rusting machinery and broken glass lying around old mining sites; there’s extensive cattle station infrastructure in the form of fences, stockyards, windmills and water troughs. There are artesian bores and pipelines, linked by roads and tracks heading off all over the place, many heading in the direction of the nearby Olympic Dam monster mine at Roxby Downs. There are scatters of flints created in the manufacture of stone tools, remnants of a different kind of industry. All of these artefacts trigger stories of particular endeavours and particular people operating at different levels within the overall historical narrative.

At Finniss Springs I feel close to a kind of ideological coalface, where the impacts of industry were brutally apparent. (We’re all consuming copper as a vital component of the electronic appliances we use every day, but for most of us it’s easy to disregard the place where the copper comes from, and the cost of its extraction.) The multiple layers of industrial detritus scattered around the place are confronting — evidence of so many booms and busts. Surrounded by the ruins of successive enterprises, things built and then crumbled, I can detect the shadow of Shelley’s “Ozymandias.” Most acutely, I could sense how this remote stretch of country might easily be written off as a kind of “sacrifice zone,” readily expendable in the quest for mineral wealth. Facing off against the tantalising promise of jobs, shareholder returns and executive bonuses, some ancient mound springs and a few dancing brolgas probably don’t stand much of a chance.

Once, camping out at Hermit Hill in a sheltered spot near the old Finniss stockyards, my friend Cameron Robbins and I were troubled by a strange, intermittent whistling coming to us on the wind. Wandering around the next morning, we traced this sound to the withered carcass of a horse lying on the windward side of a small dune not far from our camp. A scrap of desiccated hide clung persistently to the ribcage, and the wind blew fitfully and mournfully through the skeletal chamber. Sometimes the ghosts out here can seem just a little too restless or intimate; we relocated our camp. •

This is an edited extract from Talking Sideways: Stories and Conversations from Finniss Springs, recently published by UQP.