Every week, roughly 3000 Australians die. Such is life. We all know that our bodies will wear out eventually, even if we care for them well. Our immune systems erode and fail to protect us as they once did. Something will get us in the end.

We rarely even talk about it. The TV news, newspapers and ABC radio don’t ignore every other story because 3000 of us died last week. Our governments don’t order us to stay home until we stop dying — unless some of us are dying of coronavirus.

In the past week, thirteen Australians died of coronavirus. The week before that, it was twelve. Yet in that time roughly 240 times that number of Australians died of other causes, from cancers to heart failure to dementia. Why has one small group of deaths seized control of the national policy agenda when the rest are ignored?

A month ago, the reason was obvious. Look at Wuhan, our leaders said. Look at northern Italy, look at Europe in general. Coronavirus was a sinister threat we were still discovering: more infectious than the common flu, more deadly, and spread by human contact. Minimise human contact, and you minimise the spread of the virus. So Australia chose border closures and lockdown as its coronavirus strategy.

And it’s worked. On 28 March, Australia’s health authorities reported 460 new cases of the disease. Yesterday they reported eight. As of Thursday, only 1537 people were still regarded as active cases, and only forty-six were in intensive care. The death toll so far is seventy-six — a small fraction of the 1255 Australians who died in the largely unnoticed 2017 flu epidemic.

But lockdowns are a very expensive strategy. They force masses of people out of their jobs. Expensive equipment and human skills sit idle. Businesses large and small find themselves with fixed costs but no revenue, risking their future. And while the federal government has underwritten part of these losses, it is only part, and it will come at its own cost in future years.

In the United States, twenty-six million workers have lost their jobs. Australia’s economic data mostly comes with a long time lag, but a new series created by the Australian Bureau of Statistics implies that as many as 700,000 Australian workers became unemployed in the first week of April alone. If we have lost jobs at the same rate as the Americans, that would imply that so far the lockdown has made two million of our workers jobless.

Australia is now at a crossroads. Handing control of policy to the doctors has delivered fabulous results on the medical front, at what could become a massive economic cost. For Australians who are still employed but working at home, I get the sense that it’s been a kind of semi-holiday: yep, you do some work over the phone or the internet, but with a lot of free time in warm weather to spend riding bikes with the kids, jogging, working in the garden, organising tradies to come and fix things around the house, and the rest.

That won’t last. Winter is coming, and people’s savings are depleting. It is pretty clear that in Scott Morrison’s mind there are real questions about how long the lockdown can remain — especially when the number of new cases daily is now in single figures, or low double figures.

The PM has hinted strongly that at some point not too far away, he wants to switch to a policy to “test, trace and quarantine” the new carriers and all those who might have been exposed to them — and, while keeping border controls, phase out the lockdown policies that do most economic and social damage.

We do have policy choices. For when we look at the countries that have been most successful in tackling the virus, one thing stands out: their core policies were border controls, public education, and above all, test, trace and quarantine. With one recent exception, none of them has implemented lockdowns as we have experienced here.

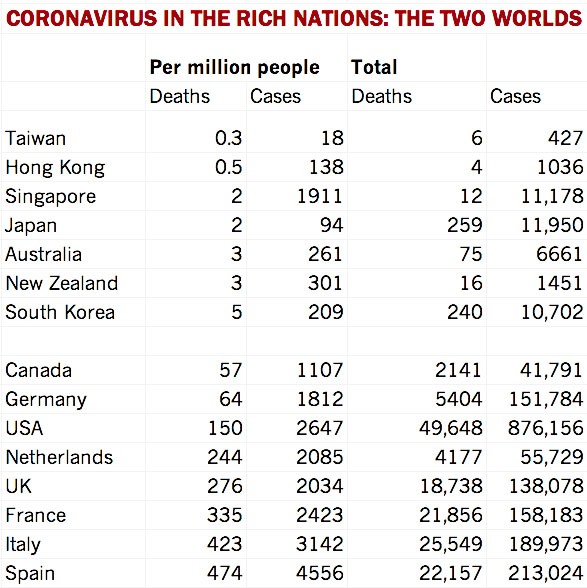

Source: Worldometer. Data downloaded 23 April 2020.

Coronavirus has divided the affluent world in two. In Europe and North America, it has proved deadly on a stunning scale. Canada has handled it better than the United States, and Germany far better than its neighbours, but even they have roughly twenty times the death rate seen here. The United States has had fifty times our death rate, and Spain 150 times. And note: by and large, these countries went into lockdown roughly when we did, if not sooner.

Yet in the affluent countries of Asia and the southwest Pacific, coronavirus has had far less impact. Australia has been a global stand-out, as has New Zealand, but the world leaders in managing this crisis have been the countries we used to call Asia’s economic tigers.

None more so than Taiwan. The one country excluded from the World Health Organization, at China’s insistence, has been the world’s most successful country in fighting the virus. In a land with almost as many people as Australia, only six people have died, and 426 have been infected. Yet the rest of us have shown little interest in finding out how they have done it.

It wasn’t by lockdowns. Large gatherings are banned, but Taiwan has remained open for business: you can go to work, school or university, go shopping, go to a restaurant with your friends. But you will have to wear a face mask in public, obey social distancing rules, and constantly have your temperature checked and your hands sprayed. If you’re ordered to self-quarantine, the government will phone you frequently to check that you don’t leave home.

Taiwan had been a victim of the SARS epidemic in 2002–03, when seventy-three Taiwanese died partly because China denied it crucial information. This time it was first off the mark.

On 31 December, the same day that China finally notified the WHO of an outbreak of respiratory disease in Wuhan, Taiwan imposed health checks on everyone arriving from Wuhan. These were gradually widened, and after China allowed a team of Taiwanese doctors to visit Wuhan in mid January, their grim report led Taiwan to embark on its strategy of test, trace and quarantine.

Back in January, when Chinese scouts started buying up Australia’s supplies of medical equipment, Taiwan banned the export of face masks — and got its industries to produce them, as they are now doing at the rate of some millions a day, along with other essential medical supplies and protective equipment. It moves fast when it needs to.

Those ordered to self-quarantine receive a daily allowance of roughly A$45, and are brought food and other necessities by their village leader. It helps that medical care is cheap and widespread, and that Taiwan is a Confucian society where people tend to obey government orders (unlike Italy, say).

The other East Asian tigers followed similar policies. Hong Kong has been another remarkable success, the more so given the intensity of its ties to China — which prevented it closing the border — the political turmoil and division of the past year, its extreme housing density, and its role as a global aviation hub.

In a city of seven and a half million residents, only four have died, with 1036 people infected. Like Taiwan, Hong Kong got in early, examining visitors from Wuhan, then anyone who had visited the town, and eventually requiring everyone crossing the border from China to go into fourteen days’ quarantine (since reduced to ten days because of overcrowding).

Even in January, public servants were being urged to work from home, although by March most were back at their desks. Hong Kong’s government did close schools, but otherwise it has led by exhortation; the city has had no lockdown. But like Australia it has progressively tightened border controls: the airport is still open to the few planes still flying, but the city is closed to non-residents.

Test, trace and quarantine has been its core policy. People are free to come and go. But a survey in February found 99 per cent of Hong Kong’s people were wearing masks on the street — by their own choice — and 85 per cent said they were avoiding crowds. Given the deep political division between government and people, their unity of purpose has been remarkable.

Singapore until recently was praised as having the world’s best policy on coronavirus. Until 21 March, despite being a major aviation hub, it had recorded no deaths from the virus and only several hundred cases. It too relied on a policy of test, trace and quarantine, backed by firm social protection rules. It kept business going, schools open and, for as long as possible, its borders open to all flights except from known hotspots.

That has now changed, for two reasons. In the second half of March, its case numbers began soaring as Singaporeans returning from Europe and the United States brought coronavirus back with them, and its quarantine rules proved too lenient to isolate them effectively.

Then the government opened Singapore’s own dark cupboard — and discovered that vast clusters of coronavirus cases had developed in the overcrowded dormitories where it houses the low-wage Bangladeshi and Indian labourers who build its world-class infrastructure. As prominent lawyer-diplomat Tommy Koh posted on Facebook, “the dormitories were like a time bomb waiting to explode.”

So three weeks ago, prime minister Lee Hsien Loong announced a dramatic policy shift. To isolate the labourers, dozens of dormitories have been locked down. Schools have closed, and people have been ordered to stay home except for essential activities. Changi Airport is still open, but operating at only 2 per cent of capacity. Singapore now has more or less the same policy as Australia.

That hasn’t stopped its case load rising rapidly — yesterday alone it reported 1037 new cases — although the vast majority of them were South Asian workers quarantined in their dormitories. Singapore still has recorded only twelve deaths from the virus.

The one Asian tiger with a higher death rate than Australia’s is South Korea. That was mainly thanks to the Daegu-based Shincheonji religious sect, which regards illness as a sin and covered up a massive coronavirus outbreak in February among its followers, some 9000 of whom showed symptoms. They infected their neighbours, and their neighbours infected the nation. By the time the authorities found out, it was too late.

But despite that discouraging start, South Korea too has used the test, trace and quarantine policy to great effect. It set up drive-through centres to encourage people to be tested, chases down everyone testing positive and those in contact with them, and uses phone apps and intrusive monitoring to ensure that those quarantined stay in quarantine. The new cases have slowed dramatically, to just eight yesterday; the deaths so far number only 238.

South Korea, too, avoided the economically destructive path of lockdown. Of all the East Asian tigers, only Singapore has adopted it, and then only recently because the time bomb of overcrowded dormitories exploded and it had to shelter its citizens. The Asian success stories tell us that you can control coronavirus without lockdowns.

Australian authorities have followed all this closely and borrowed any policies they felt would work here: that’s one reason we have done so well. Another, of course, is that we are a distant island continent, able to seal ourselves off from the world.

And let’s give credit where credit is due: our governments have done a bloody good job of leading us out of the crisis. You can criticise one decision or another, especially in Victoria and New South Wales, which were under most pressure. But by and large, I can’t remember any crisis in my lifetime that a government has handled better than this. And much of the credit for that has to go to Scott Morrison, who for the first time has looked and acted like a real leader.

Until now, the doctors have been directing policy. But now it’s a more subtle issue: getting the right balance between lives and livelihoods, keeping the infection rate low while allowing people to get back their jobs, incomes and opportunities.

The issue now is how we return life to something like normality, where people are back at work, schools, accommodation and restaurants are open, and people are free to move around. And instead of state governments telling us the four things we’re allowed to do, they tell us the few things we’re not allowed to do. Plus, we need to do all this without losing control of the virus.

The first loosening will begin next week, when some forms of elective surgery will be allowed. It’s a very cautious start, and still in a medical area. Australia’s chief medical officer, Brendan Murphy, indicated to a parliamentary committee yesterday that his team has been asked to consider allowing more than two people to meet at once, lifting the ban on community sport, and reopening some retail sectors now forbidden to operate.

Morrison has floated the idea of reopening the trans-Tasman border while maintaining border controls on the rest of the world. New Zealand’s experience has been similar to ours, leading its government (which faces an election in September) to begin relaxing some restrictions and to foreshadow more relaxation ahead. Federal education minister Dan Tehan has urged the states (Victoria, that is) to have all schools open again by 1 June.

But all this would still leave Australia’s lockdown mostly intact. Much of that was imposed by the two largest states, and this week their premiers, Gladys Berejiklian and Daniel Andrews, dug in hard, claiming that any loosening of restrictions would lead immediately to a rapid spread of the virus. On Wednesday Andrews effectively presented the choice as being between the current restrictions or tens of thousands of deaths. Perhaps he’d had a bad day.

Yet many Australians think like him: Twitter is full of otherwise intelligent people who see the issue in black and white. No doubt both leaders will bring more nuanced minds to the national cabinet table when it makes its decisions in mid May.

But the two premiers’ positions underline the fact that the path to reopening the Australian economy — and restoring jobs and incomes to those workers now bearing the real cost of delivering us from the nightmare we expected — could be long and difficult. •