The anthropologist W.E.H. Stanner’s phrase “the great Australian silence” is repeatedly quoted alongside expressions of relief that the silence is over. The space devoted to Aboriginal issues has filled with demands, discussions, depictions and disputes about the atrocious conditions Aborigines have endured and how to ameliorate them. But while those conditions were certainly hidden from public scrutiny for several decades before Stanner spoke in 1968, there had been a lot of talk about Aborigines in the corridors of power.

After the last massacres in Western Australia and the Northern Territory in the 1920s, the governing of Aborigines became a matter of intense concern to state and territory politicians and their advisers, agents and emissaries. In this new era — the protection era — paternalistic control masqueraded as care. No longer would white pastoralists, farmers and country residents be free to remove or enslave the local Aborigines.

Between the 1920s and the referendum in 1967, each state passed and frequently amended protective legislation, creating a great body of law that attempted both to separate and to assimilate Indigenous populations. The convoluted complexities that emerged reflected beliefs about race that remained unquestioned for decades and still lurk in disavowed corners of Australian consciousness.

The foundational fantasy was that two separate and unequal kinds of human beings, known as two races, the Whites and the Aborigines, lived in Australia. “Foreign” races also lived here, but they could, if necessary, be sent back to where they came from.

That fixed fantasy of separate and unequal races was the common sense belief of the times. It did not necessarily imply enmity, let alone brutality, and it was sometimes accompanied by sincere compassion and care, albeit founded on inequality.

But while separation and inequality were seen as natural, considerable force was needed to ensure they were maintained. Separation in particular, but also the inequality between Whites and Aborigines, was being undermined by an inexorable process that scientists had named “miscegenation.” This “problem” was often referred to as “the half-caste menace,” because the “mixed race” population menaced racial binarism.

It was when I was trying to make sense of the position of Rembarrnga people, with whom I lived intermittently in the 1970s and 80s, that I discovered the legal minefield that had been the Northern Territory’s racial frontier just a few years earlier.

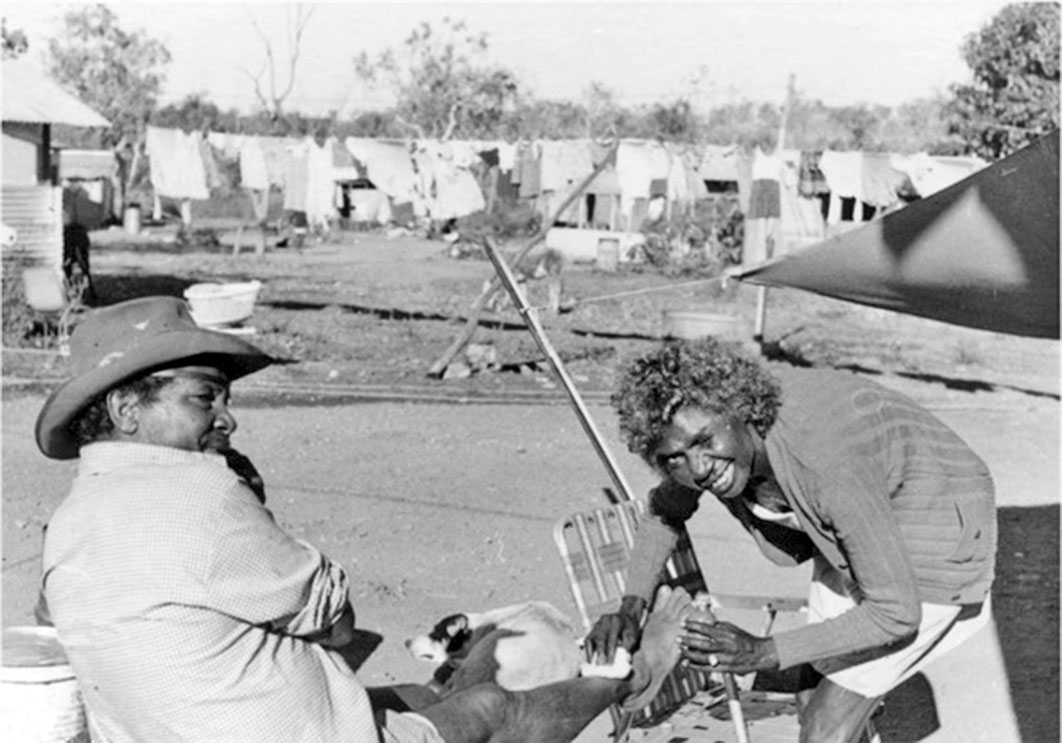

This was at Gulin Gulin, better known as Bulman, just inside the southern border of the Arnhem Land reserve. The Rembarrnga families were refugees from Mainoru cattle station, where most of them had lived and worked since the 1920s. Two disasters had occurred in 1969. With the death of Jack Mackay, the old and trusted owner of Mainoru, the station was sold. Because government subsidies had been withdrawn and equal wages introduced, the new managers stopped providing rations for the families in the camp. Individual contract jobs were offered to a few stockmen and the rest of the community was made unwelcome. After weeks of tension, the Rembarrnga families walked off the station, trekking north to a safer place.

A major focus of the earlier laws had been to control interactions between the races, especially the intimacy that had led to the emergence of “half-castes.” Their existence was routinely attributed to “combos,” a contemptuous slang term for white men who “consorted” with the Aboriginal women, who gave birth to “yella fellas.”

It now seems an obvious absurdity that such relationships were deemed a serious social problem. Yet it preoccupied respected and responsible politicians and public servants, and they devised an array of laws and regulations to discourage and administer “interracial” relationships. Because such matters were embarrassing, they were debated among the lawmakers rather than in public. In the southern cities and towns, Aboriginal people had been separated from their land and severed from their heritage for more than a century and were already largely “mixed race.” The legal restrictions Aborigines faced there were different, though in many ways more repressive — but that’s another story.

The laws devised for the Northern Territory defined where members of the two races could legally gather and reside, including the town areas from which Aborigines were prohibited, and camping areas and reserves for Aborigines only. The changing rules were mainly directed at town and fringe dwellers and were published in the government gazette each week. As John McCorquodale has written, a “bewildering array of legal definitions led to inconsistent legal treatment and arbitrary, unpredictable, and capricious administrative treatment.”

State and territory governments modified their statutes as conditions changed, new challenges arose, other jurisdictions acted, and international ideas arrived. A critical task was defining an “aboriginal native” to whom these laws applied. The Northern Territory’s 1924 Aboriginals Ordinance extended the definition of “an aboriginal native” to include “half-caste males below the age of twenty-one.” It was extended again in 1927 to take in those males “whose age exceeds twenty-one years and who, in the opinion of the Chief Protector [of Aborigines], is incapable of managing his own affairs and is declared by the Chief Protector to be the subject of this Ordinance.” Applying these laws often entailed intrusive examination of individuals.

These laws were mostly ineffective against irresponsible or violent white men while punishing sustained, amicable relationships. A tin miner at Maranboy, for instance, had his “licence to employ Aborigines” cancelled after being accused of “abduction” and then of “associating” repeatedly “with female Aborigines.” It was then reported that “the girl may have been party to the offence,” before the police finally admitted that the same “girl” was involved each time. This man was being harassed for criminal and immoral acts on the basis of his loyalty and fidelity to his de facto Aboriginal wife.

In remoter areas, light-skinned children in “blacks camps” were routinely removed to institutions to be educated for a few years. This was justified partly because such children were allegedly treated badly by their “full-blood” relations. Rembarrnga people were baffled by and indignant about these laws, which I believe was based on a blatant lie. The mother and other relatives of a light-skinned baby who had been taken to the “half-caste home” in Darwin received news of how she was faring over the years from a sympathetic patrol officer, and the daughter, now an adult, eventually reconnected with her mother. “The government was silly then,” said the mother, voicing a general view. “They’re better now.”

Rembarrnga recognised differences between blackfellas, whitefellas and yellafellas — they used these vernacular English terms — but did not accord them different human value. They did not understand racism.

A principle of “not disturbing the tribal life of the natives” was agreed to by the territory administration and the Northern Territory Pastoral Lessees Association at a conference in 1947 in Alice Springs. Thus, remote Aboriginal communities suffered less disruption by state officials than those in or near the towns. In Darwin and Alice Springs, the laws of separation proved to be ever more complex and confusing. Demeaning designations and restrictions — such as permits allowing a specific white man to associate with a specific Aboriginal woman between the hours of 6pm and 9pm on Saturdays — were increasingly challenged as the years went by.

Underlying that kind of restriction was the fact that it was against the law for white men to “consort” with Aboriginal women. Any intimacy between white women and Aboriginal men was unthinkable because such relationships contradicted both the racial and sexual hierarchy. The law echoed the widespread contempt for the men concerned. Only brave white men openly established relationships with Aboriginal women and acknowledged the children they fathered.

Xavier Herbert brought this barbarity to light in his great novels Capricornia (1938) and Poor Fellow My Country (1975). Ted Egan’s song “The Drover’s Boy” reveals another way stockmen and women evaded the racial separation laws — the drover’s boy was actually a girl. The territory administration attempted to put a stop to this practice by forbidding female Aborigines from dressing in men’s clothing under penalty of a substantial fine.

I was surprised to find that the original Aboriginals Ordinance, introduced in 1918, had given the territory’s director of native affairs the power to issue a “mixed race” couple with a “permit to marry.” Although very few applications were made before the 1940s and only about eight between 1944 and 1948, many more were granted in the 1950s.

Three Rembarrnga women I knew had married white men under these conditions, but none had children. None of the three was literate, and all were clearly baffled by the legal constraints but proud of managing to overcome them. Rumour had it that such women were routinely subjected to medical procedures to render them infertile.

Judy Farrar, an old woman when I met her in 1976, had lived openly with Billy Farrar when he owned Mainoru station. She told me that the policeman had “chased them” but they gave him the slip. After that, Judy said, “they gave me a white dress for married, properly way.”

The Farrar family were pastoralists, but it appears that Billy’s participation in the social life in Katherine was severed after the marriage, which must have been about 1940. Judy remained with Billy Farrar until he died. He left her £46 in his will.

Alma Gibbs married stockman Jimmy Gibbs around a decade later, after two local government officials came to Beswick Station to interrogate them. This is how Alma described the scene to me:

That’s the time we got caught. Native Affairs came out because somebody reported us two. They came to Beswick at night time, all that lot.

Jimmy Gibbs said: “Hey, all the welfare are here. They’ve come after you and me.”

“Alright, they can come,” I said to everyone.

They carted up all the books. And they brought up two or three boys [Aboriginal men] too, to give me a black one.

“Well,” they said, “we can’t let you marry that man. You pick which boy you want.”

“I won’t pick anybody,” I told them like that. “I’ll stop with this old man.”

“No you not allowed. He’s not a young man. He’s a bit old for you.”

“No matter he’s an old man I’ll stay with him. I work for him. I can’t help myself. I’ve got to look after his clothes, everything for him. You can’t make me feel different.”

“No you’re not allowed. You’ve got to marry your own colour,” they said.

“I don’t care about my own colour. I’m married to this white man. You can’t make the law all the time,” I said to them. So they had to believe me.

“Alright, well, do you want to be married?”

“No, not married to him, I want to live with him, that’s all.”

After that they said, “That’s alright, you two can walk about free now.”

Alma and Jimmy were issued the permit and a white dress was supplied for the wedding party at Bamyilli. The liberal regime on Mainoru station protected such couples from public contempt. But couples who didn’t request permission to marry were sometimes hounded through the bush by police and patrol officers for years.

The third woman I met was Nelly Camfoo, who had married Tex Camfoo. Tex’s racial status reveals the absurdity of the laws. He was not classed as “an Aboriginal native” but nor did he fit the new category of “ward,” which had been created in the mid 1950s in a legislative move of breathtaking simplicity by territories minister Paul Hasluck. The Aboriginals Ordinance became the Welfare Ordinance; it no longer applied to a race but to those who were “unable to look after themselves.”

Because Tex’s father was Chinese, he had been removed from his Aboriginal family to Groote Eylandt as a “half-caste” child. Because the education he received there meant he wasn’t regarded as someone “unable to look after himself,” he was a European by default and needed a permit to marry Nelly.

As they tell it in Love Against the Law, these events were both hilarious and horrifying. Tex told me he said to the police officer, “Well, anyhow, I didn’t know I was a European,” to which the police officer replied, “Your father is a Chinaman. They haven’t got that law so your father’s a European. You follow your father. Your name’s Camfoo.”

This illustrates the widespread confusion caused by the desire to categorise people in terms of race. The newly invented category of “ward” silenced emerging complaints about racial injustice and ended legal challenges to the Aboriginals Ordinance. The number of wards would gradually contract as the assimilative process inexorably continued. An individual who ceased to be a ward would be severed from their relatives to become an individual European.

No distinct Aboriginal social realm with legitimate, autonomous cultural practices was recognised in the legislation. Or rather, the principle of “not disturbing the tribal life of the natives” was followed by ignoring “tribal life,” at least until valuable minerals were discovered beneath the surface of the natives’ lands — but that’s another story, too.

That “full-bloods” were in need of care by the state — meaning in their interactions with white institutions and practices — was thought so obvious that it was not detailed or defended. But the attempt to develop a register of wards failed. The intricacies of Aboriginal kinship and naming systems — the lack of a system of surnames, for example — baffled the patrol officers and police charged with listing wards by name.

Another common assumption was that Aborigines would welcome the chance to assimilate with the white world and readily divest themselves of their own “primitive” ways of being. While the assimilative forces puzzled people like Alma Gibbs and Nelly Camfoo, evidence that Aborigines wanted to retain their relationships and way of life puzzled many a policymaker working hard on “improvements.” “Improving” or “assimilative” ideas prevailed among the governing class for a century or two and still lurk in unconscious corners of Australian ideology.

William Faulkner was writing of the deep south of the United States when he said, “The past is never dead. It is not even past.” He traced the intricacies of racialised understandings of the world and the legacy of cruelty and hypocrisy across American society. Racial laws and practices in Australia were and are very different, yet the legacy of the laws I have described and the ideas that gave rise to them live on in what I think of as the naturalisation of inequality. In these matters we are all driven by perceptions and sentiments formed by a social history that is beyond our individual will.

The “bewildering array of legal definitions” of Aborigines and the attendant forms of control and interference dissolved when the Commonwealth government assumed control of Aboriginal affairs across the continent after the 1967 referendum. Rather than rejection, Aborigines then experienced far greater public and political attention, and a sometimes suffocating embrace. While the quantum of sympathy and concern increased exponentially, so did the accompanying hypocrisy, as the same fundamental conditions of separateness and inequality remained.

In rural communities, white resentment grew as Aborigines appeared to be favoured. The continuing marginalisation and poverty of the majority of Aboriginal communities, combined with their own desire for “difference,” has meant that police — who are seldom interested in either history or culture — are left to deal with the difficulties such conditions inevitably produce.

Australia’s political class now claims to respect traditional owners of the land, asserting pride in the “oldest culture in the world” and scorning explicit racial hostility. Yet the complexity and sophistication of traditional as well as contemporary Aboriginal social worlds are little understood. Perhaps this is just as well, because their underlying principles and values contradict those of the settlers. As anthropologist Ken Maddock, who worked with Rembarrnga men some years before I was there, wrote in 1974:

The polity of the Aborigines… with its freedom from any institution of enforcement, and its consequential stress on self-reliance and mutual aid within a framework of generally recognised norms, was a kind of anarchy… in which none were sovereign.

The Aboriginal voices heard in public today may chip away at the prejudices evident in white Australia, but even the most powerful of them can readily be dismissed — as was evident in the federal government’s response to the Uluru Statement from the Heart.

The Uluru Statement was composed by respected and responsible Aboriginal people after many months of consultation with communities across the country. That a decent-enough human being like Malcolm Turnbull could so easily and hurtfully dismiss it on bogus grounds seems to me a reflection of the lack of importance accorded to Aboriginal people among the political and economic priorities of contemporary Australia. But the fact that Turnbull was criticised for his response, and that widespread support emerged for the projected future proposed in the Uluru Statement provides us with a ray of hope that black lives may matter as much as other lives in Australia’s future. •