In Satyajit Ray’s 1955 film Pather Panchali, the first instalment of his “Apu” trilogy, a father returns home to be told by his wife that, in his absence, their young daughter has died. We don’t hear the wife’s words; we see her mouth open to speak and we hear music. It is the wail of a tar shehnai, a bowed esraj amplified through a gramophone horn, and it sounds uncannily human. The notes it plays belong to Patdeep, an afternoon raga sometimes associated with blazing heat, sometimes with love and the pain of separation. Ravi Shankar was the composer, and as Oliver Craske, the author of a new biography, suggests, the musician’s early life seemed to have prepared him for this moment.

Born one hundred years ago to parents who were Bengali Brahmin, and given the name Robindra, shortened to Robu or Robi, Shankar was raised by his mother in Benares (Varanasi). He didn’t meet his estranged father until he was eight years old. Because of the estrangement, the family was poor. At around this time the boy began to suffer sustained sexual abuse from “a family member.” Shortly before his ninth birthday, his favourite brother, Bhupendra, died of the plague. Like Ray’s Apu, he lost both parents while still in his mid teens.

Another aspect of Shankar’s early life also has a bearing on his work as a film composer. From childhood he was a storyteller, not through music — that came later — but through dance. Joining his eldest brother Uday’s international dance troupe, the boy became a performer on the world stage, touring Europe and the United States. In his diary of April 1933, the nineteen-year-old Benjamin Britten singled out the thirteen-year-old “Robindra” as a highlight of the performance he had witnessed in London.

Late in life, Ravi Shankar would complain that he had missed out on a childhood, but at the time he enjoyed meeting the celebrities of the day, including Greta Garbo and Myrna Loy. At a party in Hollywood, the actor Marie Dressler asked Uday, in all seriousness, if she could adopt the boy.

“Robi” is the Bengali word for sun. In Sanskrit, the word is “Ravi,” the name he took around the age of twenty. Craske’s book, Indian Sun: The Life and Music of Ravi Shankar, is the first biography of the musician, with the exception of Shankar’s own memoirs, the last of which, Raga Mala, was a collaboration with Craske. But in spite of its writer’s closeness to his subject this new book is no exercise in hagiography. Shankar himself encouraged the author to wait until after his death and tell the whole story, and Craske seems to have done just that.

Better yet, Indian Sun is that rare thing, a biography of a famous musician in which the music is kept in the foreground and knowledgeably discussed. The book’s preliminary pages include a detailed diagram of a sitar, an explanation of the steps in an Indian octave, and lists of the ragas Shankar created and the talas (rhythmic patterns) he commonly employed.

Shankar didn’t take up the sitar until his late teens — very late indeed for someone who would become the most celebrated sitar player in history — but he worked hard and learnt fast. His guru was Allauddin Khan, not himself a sitar player but a master of the sarod. In short order, Ravi was allowed to play jugalbandi with Khan’s son, Ali Akbar Khan, another sarod player. The pairing of sitar and sarod on equal footing (which is what the term jugalbandi implies) was rare, even experimental. It was a sign not only of the faith Khan had in Shankar (who also married Khan’s daughter, Annapurna) but also of things to come. From early in Shankar’s musical career, his playing received praise and criticism in equal measure, the criticism nearly always for a want of purity.

Shankar had a Zelig-like tendency to be present at great historical moments. As part of Uday’s dance troupe, for example, he witnessed the rise of Hitler. Until 1933, Germany had been the country in which the Indian dancers felt most appreciated. In New York he heard Cab Calloway at the Cotton Club. He sang for Gandhi and received a blessing from Rabindranath Tagore. All this before he turned eighteen. As Craske underlines, though, the greatest example of Shankar being in the right place at the right time — twenty years before he moved to California, just before the Summer of Love — was his emergence as a charismatic cultural figure in India at the moment of that country’s independence. Before he taught the world about Indian classical music, he demonstrated its value to a nation emerging from the shadow of colonialism.

By the mid 1960s, Ravi Shankar had become not only a famous musician but a global celebrity, his influence felt everywhere — certainly in musical circles. After lessons with Shankar, John Coltrane felt he was “just beginning again,” and went on to name his son Ravi. Yehudi Menuhin regarded himself as Shankar’s disciple and recorded albums of music for violin and sitar. And in 1965, Shankar changed the lives of two young musicians: one was among the most famous musicians on the planet, the other a recent music graduate from Juilliard.

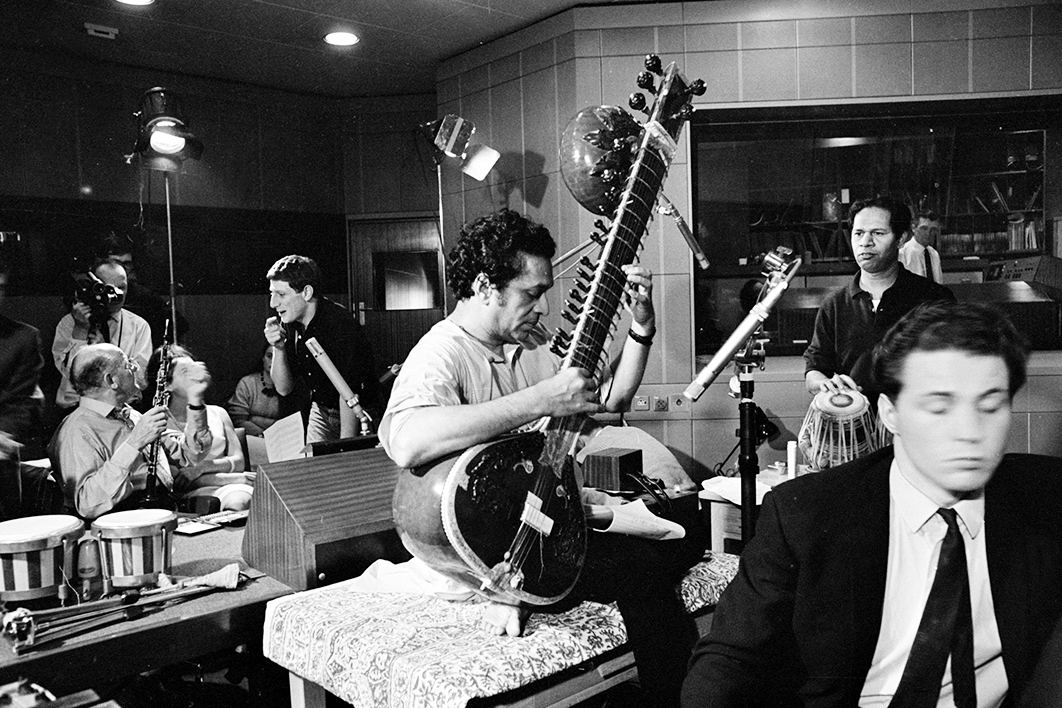

George Harrison’s debt to Shankar is well known (Shankar greatly appreciated the Beatle’s seriousness and modesty), Philip Glass’s less so. In Paris, pursuing his studies with Nadia Boulanger, Glass found himself engaged to assist Shankar with scoring Conrad Rooks’s film Chappaqua. Shankar would sing lines to Glass (who was impressed that he had all the music in his head) and Glass would write them down in Western notation. But such notation required bar lines, and when the music was played there were unwanted stresses on the down beats. The barlines were moved and the stresses moved with them. “All the notes are equal,” explained Alla Rakha, Shankar’s tabla player. Finally, the barlines were eradicated and the music worked. Whether or not he realised it at the time, Glass had probably just received the most important composition lesson of his life.

Craske’s book leaves little out. Shankar’s international touring is described in such detail we begin to glaze over, but perhaps that’s the point. How, we wonder, did he fit so much in? And how did he manage his 180 affairs with women? (And who was counting? Did he have his own, personal Leporello?) And there are copious nuggets of trivia. Among my favourites is the fact that Peter Sellers went to Shankar for guidance about how to look like a sitar player in Blake Edwards’s film The Party. In the film, Sellers, in “brownface,” plays a hapless Indian actor mistakenly invited to a Hollywood party at which he proceeds to wreak havoc. Satyajit Ray, for one, found Sellers’s performance repellent. But Shankar and Sellers were quite close for a time, even working up a double act for friends, in which they impersonated each other.

To the end of this mighty book, Craske rightly prioritises the music. The penultimate chapter, “Late Style,” discusses Shankar’s final compositions. By his eighties, although he occasionally performed alongside his daughter, Anoushka, using a modified sitar with a short neck, he was mostly a composer. He wrote an opera, Sukanya, named after a woman in the Mhabharata who marries a much older man. It was a name shared by Shankar’s second wife, and the opera is both an extended love letter to her (there’s a musical motto based on her name) and a hymn to Krishna. But it is also a grand summing up of Shankar’s musical life, reworking ragas that had been important to him — Piloo, for instance, which he had recorded with Menuhin — and other earlier compositions.

The music to Sukanya was written first — is there another opera for which the music was composed ahead of its libretto? — and words fitted only after Shankar’s death in 2012. The premiere was in England in 2017. The same year, at the London Proms, Passages, Shankar’s album-length collaboration with Philip Glass, had its first live performance, with Anoushka Shankar playing sitar. The event was televised live by the BBC. As Craske writes in the title of his final chapter, this sun “won’t set.” •