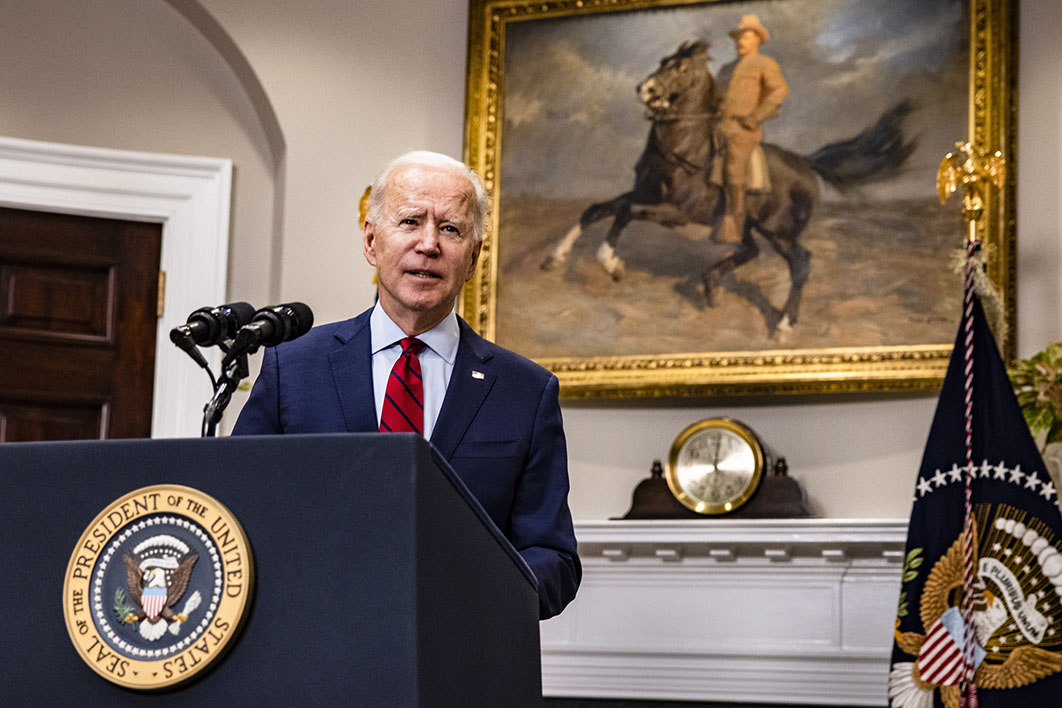

The passage of the American Rescue Plan, Joe Biden’s US$1.9 trillion pandemic relief bill, is not only a crucial development in US politics; it also has important implications for Australia. Widespread support for the package among Americans contrasts sharply with the generally negative response to the only major economic legislation passed under Donald Trump’s administration, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017. The shift in opinion indicates that, despite the bitter divisions of the Trump era, public opinion on economic issues has moved sharply to the left.

The passing of Biden’s legislation is the result of both his presidential election victory and the run-off elections in Georgia, which gave the Democrats fifty votes in the US Senate (with vice-president Kamala Harris holding the casting vote). The central issue in the Georgia elections was the choice between the relatively modest stimulus package passed by Congress in December 2020 and the much more ambitious proposals from the Democrats. In hip-pocket terms, the distinction was between the payments of US$600 per taxpayer from the Republicans and a total of US$2000 offered by the Democrats.

That wasn’t the only difference. The Republican legislation allocated nearly a third of funds to the Paycheck Protection Program, a version of Australia’s JobKeeper, but gave nothing to state and local governments. Because their tax revenues have been reduced by the pandemic, and because they have little or no capacity to run deficits, state and local governments in the United States have been forced to cut spending and employment. Biden’s package includes large-scale support for these levels of government.

The measures in the Rescue Plan are temporary and most are expected to cease as the economy recovers. But the package includes funding for policies the Democrats would like to make permanent, the most important of which are increases in the Earned Income Tax Credit and the Child Tax Credit, the two main measures that assist families with children. If sustained, these increases would reduce child poverty by an estimated 40 to 50 per cent.

Republicans’ opposition to the package may safely be dismissed as political posturing, given their eagerness to pass the Trump cuts. But some more credible commentators, most notably Larry Summers (who held senior economic positions in the Clinton and Obama administrations), have expressed concern about the scale of the stimulus.

These concerns have mostly focused on inflation and the growth of budget deficits and public debt. A more useful way to consider the problem (an approach sometimes referred to as functional finance) is to ask whether the resources available to the economy are sufficient to meet both the extra public expenditure in the stimulus package and the rise in consumption and private investment expenditure that follows.

For the moment, finding those resources isn’t a problem. The conditions created by the pandemic have reduced private consumption and investment expenditure. Households whose incomes have been unaffected by the pandemic have used the money saved by working from home and limiting holidays to pay down debt. Businesses have held off big investment decisions.

But once life returns to normal, and spare capacity in the economy is exhausted, households will want to start spending the liquid assets they have built up. Their increased demand will collide with permanently higher levels of public expenditure and renewed investment to produce a level of aggregate demand beyond the capacity of the economy to supply.

The outcome will create shortages, rationing and bottlenecks — which means none of these demands will be satisfied. Eventually, the shortages will produce higher prices and wages, and a renewed burst of inflation. But inflation is just a symptom of excess demand; it’s the shortages, and the problems they create, that are the real source of economic damage.

Once the economy recovers, the only way to meet the need for increased public expenditure, given the productive capacity of the economy, will be to reduce the spending power of private households through taxation. Given the highly unequal distribution of income in the United States, most of the reduction must be borne by those in the top 10 per cent of the income distribution and particularly those in the top 1 per cent. Since these groups were the biggest beneficiaries of the Trump tax cuts, the immediate response must be to repeal part or all of those tax cuts.

What about the public debt built up during the pandemic, and the further increases in debt implied in sustained budget deficits? In the short run, much of the debt has been monetised: the US Federal Reserve has bought around US$4 trillion in Treasury bonds since the pandemic began, and will be able to buy more to offset the increase in public debt associated with the latest stimulus. But the Reserve’s capacity to do this is limited by the public’s willingness to hold cash and zero-interest deposits rather than spend their wealth or invest it in higher-yielding assets. Once this willingness is exhausted, further monetary expansion will translate into higher expenditure and therefore run the economy into resource constraints.

To resolve the situation, the ratio of debt to GDP will need to be reduced during the expansion created by the stimulus package. Fortunately, low interest rates mean that will happen automatically, as long as tax revenue is sufficient to cover government “primary” expenditure (exclusive of debt).

But a faster reduction is probably desirable. The small policy adjustments (such as twenty-five basis points in central bank interest rates) that seemed to work in the couple of decades before the global financial crisis aren’t adequate for managing the unstable economy we can expect for the foreseeable future. The larger the stimulus we want government to provide in bad times, the bigger the surpluses it should run when private demand would otherwise be excessive.

All that is for the future. If Biden’s stimulus plan achieves its goals, it will be the clearest demonstration in many years of the central role of government — in the United States and countries like Australia — in stabilising the economy and delivering outcomes more sustainable and equitable than those of unregulated capitalism. Let’s hope it works. •