The burial sites of two of Australia’s most significant founding figures have attracted attention in different ways over the past decade. Bennelong’s grave — always known to be somewhere in the modern-day Sydney suburb of Putney — is now thought to be at 25 Watson Street. On the advice of a committee of elders and scholars, the NSW government purchased the property in 2018 to establish a more enduring memorial to the Wangal leader. Arthur Phillip’s grave is inside St Nicholas’ Church in the English village of Bathampton, not far from Bath, where he spent the last eight years of his life. Several prominent Australians have bemoaned the modesty of the resting place of the first governor of New South Wales and called for his remains to be moved to Sydney.

With luck, both men will stay where they are, undisturbed by occurrences neither of them would have condoned. In Bennelong’s case, a mooted local council plan to excavate his grave for roadworks wouldn’t disturb his greatest legacy for Australians today. Long considered a tragic figure who fell victim to a clash of worlds, he is better remembered as a man who fought for his people’s interests and died surrounded by loving kin. He was buried in 1813 where he had spent much of his final years — on land the colonists called Kissing Point and had seen fit to grant to the emancipated convict James Squire.

Colonial sources report that by 1821 Bennelong lay in his grave with his last wife and another male leader. These were probably Boorong and Nanbarree, of the Burramattagal and Cadigal people respectively. Back in April 1789, as children, Boorong and Nanbarree had sought respite at Phillip’s Government House from the horrific smallpox epidemic the colonists had unleashed earlier that year. When Bennelong was brought into the colony as Phillip’s captive in November 1789, the pair greeted him with “raptures of joy.”

That Bennelong wound up buried with these two characters from the early colony’s history might tempt us to focus too much on those heady few years and imagine that Bennelong’s meaning begins and ends with his tussles with the new arrivals. In fact, like Boorong and Nanbarree, he spent most of his life away from Sydney Cove, or Warrane as he would have called it. Certainly his last fifteen years were dedicated to the many different Eora people in the surrounding hinterland.

To see 1789 as the most momentous point in Bennelong’s life is to risk putting colonial people rather than the Eora at the centre of his story. It also reinforces the view among the Europeans who lived alongside Bennelong that his time away from the colony represented a kind of absence or failure, rather than a presence and successes elsewhere.

After he was captured to serve as Phillip’s primary intermediary with the Eora, Bennelong stayed in the colony for the brief six months until May 1790. His reappearance four months later coincided with the dramatic spearing of Phillip at Gayamay, or Manly Cove — an event probably orchestrated by Bennelong himself as punishment for his earlier treatment. With the slate now wiped clean, both men worked together to broker smoother relations between their respective worlds. The two-year period from late 1790 to late 1792, often called the “Coming in of the Eora,” is better considered a fragile era of détente.

At the end of 1792, Bennelong visited Phillip’s motherland with the retiring governor and Yemmerrawanne, a younger Wangal kinsman. A little under three years later, with Yemmerrawanne having fallen ill and died, Bennelong returned alone to Sydney, mostly unchanged and unimpressed by the experience. Almost immediately he resumed the obligations, friendships and enmities of an elder Eora man. Colonial sources are littered with accounts of his involvement in battles around the harbour and in elaborate ceremonies. What colonists dismissed as a tendency to violence and the usual hedonism of savage life, however, was evidence of Bennelong’s high status and the determination with which he maintained old rituals.

Not everything could be maintained, of course. After his return from England, Bennelong led a group on Wallumedegal land north of the river rather than on his old Wangal land to the south. This conglomerate group, known as the Kissing Point tribe among the colonists, had emerged from the disorder that colonialism had brought to some clans, chiefly through disease. Colonialism had not destroyed them, though — only spurred the formation of a new organisation, no less authentic or recognised than any other.

Despite a dismissive obituary in the Sydney Gazette in January 1813, Bennelong’s death stirred large-scale mourning, and scholar Keith Smith in particular has written about the many tributes paid to him. A huge battle to avenge his demise, involving more than 200 Eora men, was seen by passers-by in April 1813. Eight years later, a travelling missionary showed an image of Bennelong to survivors at Kissing Point. “He it is!” they wept. “Bennelong! He was our brother and our friend!”

Bennelong’s successor at Kissing Point was a Burramattagal man called Bidgee Bidgee, who was described in 1828 as a frequent visitor to Bennelong’s grave “amidst the orange trees of the garden.” Bidgee Bidgee voiced a desire to be buried there too, along with Boorong and Nanbarree. We don’t know if this desire was ever fulfilled. We need not dig to find out. The key point is that Bidgee Bidgee’s request is a final refutation to the old argument that Bennelong died an outcast. Contrarily, he was widely loved.

Phillip was not Bennelong’s constant chaperone during his stay in Britain. He organised various lodgings for Bennelong and Yemmerrawanne in London, along with some new clothes and a few activities. But his involvement with the pair was sporadic at best. It seems likely that Phillip’s fiancée, Isabella Whitehead, helped nurse Yemmerrawanne during the early stages of his sickness. But neither Phillip nor Isabella was present when the young man passed away, nor did they see much of Bennelong afterwards, while he waited for his return journey.

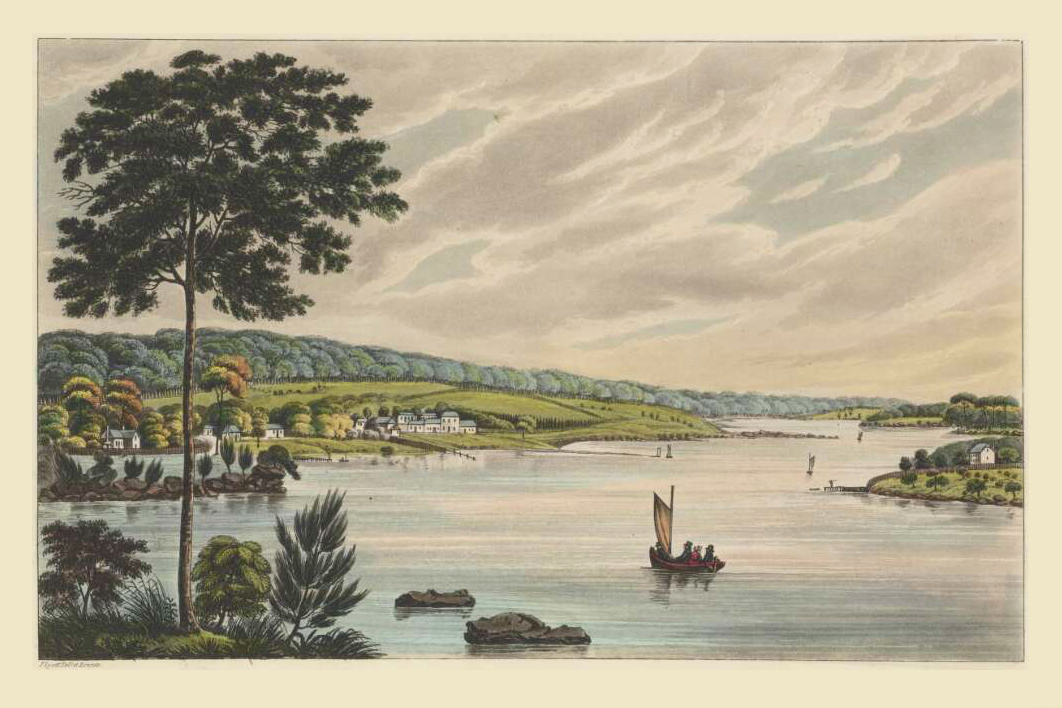

St Nicholas’ Church at Bathampton, in which Arthur Phillip was buried. From Everitt’s Views in Bath and Its Vicinity (1840).

Sporadic, indeed, might be the most apt description of all of Phillip’s involvements with New South Wales after his governorship. He wrote several letters of recommendation for old friends in the colony, though few after he helped secure the governorship for Philip Gidley King in 1800. He kept up his correspondence with the colony’s proxy patron Joseph Banks until 1796, and he once gave an audience to returned Governor John Hunter. Although his Australian biographers tend to emphasise these moments, they don’t amount to much compared with that far greater passion of Phillip’s life after New South Wales, his continued service with the British navy.

Phillip still sought naval positions during his fifties and into his sixties. The decade in which he had returned from Sydney was dominated by Britain’s war against the French Revolution, and Phillip commanded three different vessels helping the war effort between 1796 and 1798. He then led the Sea Fencibles to guard British coasts from French invasion until forced into retirement in 1805.

Such activities matched Phillip’s nearly twenty-six years of naval service before his five-year stint in Sydney. Those years included defending colonial possessions in North America, spying on imperial rivals in Europe, assisting Portuguese allies in South America, and helping to subvert French support of the American Revolution. Put together, Phillip’s career reveals a man far more preoccupied with furthering the expansion of a global empire than with focusing on one small outpost.

Phillip and Isabella spent most of his retirement in Bath, close to several addresses recently vacated by Jane Austen. Perhaps it was during their brief stay in Bathampton that they formed an attachment to its lovely church, resolving to be buried together in it one day. Isabella honoured her husband’s wish when Phillip died in 1814, just over a year after Bennelong’s death.

Influential Australians have tried to get Phillip’s remains relocated for more than a century. The Sydney Morning Herald demanded it in 1907, the Courier-Mail followed suit in 1937. Barrister Geoffrey Robertson and politician Bob Carr have lobbied for this to happen since 2001. So far the calls have resulted only in the construction of a chapel within St Nicholas’s, paid for by Australians, declaring Phillip the “Founder of Australia.”

Both the inscription and the idea of repatriation sit awkwardly with the history of Arthur Phillip. If Australia does have a founding point amid the fragile stability hard won in 1790, then it is just as much Bennelong’s achievement as Phillip’s. More significantly, the former governor himself might not have considered his five years administering a penal colony to be his greatest moment.

Phillip’s final resting place in England is a reminder of Australia’s historical role in the sweeping advance of the British Empire through the eighteenth century — an empire that dispossessed thousands and fought against two democratic revolutions. Phillip was its loyal servant, active in many of its chief developments.

If Phillip signifies expanding imperialism over national foundation, then his oft-paired counterpart Bennelong stands for the Indigenous life that yet, remarkably, persisted. Empire and Aboriginality remain the true twin pillars of Australia. •