It is perhaps unfortunate that the popular streaming options at the moment include a series called Vigil, which deals with murder and a cover-up of negligence aboard a British nuclear submarine that came close to creating “another Fukushima” in an American port.

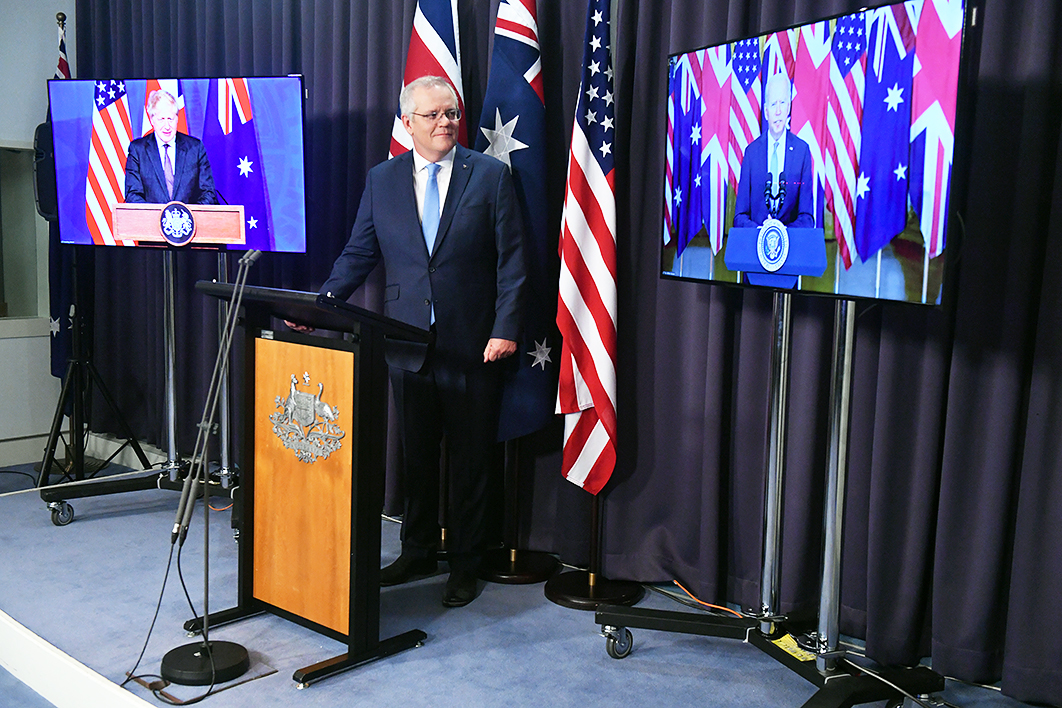

No such meltdown is known to have occurred among the navies that have operated nuclear-powered submarines over the past sixty-five years, not even aboard the USS Thresher, which was lost with all hands during deep-diving tests in 1963. Even so, a lot of public reassurance will be needed following Scott Morrison’s joint announcement with US president Joe Biden and British PM Boris Johnson that nuclear-powered submarines will be built and maintained by the Australian Submarine Corporation, or ASC, at Osborne, just outside Adelaide.

As independent senator Rex Patrick, a former submariner himself, points out, this means “nuclear reactors sitting on hard-stands at Osborne and moored in the Port River.”

American and British nuclear submarines are understood to use highly enriched uranium fuel that is close to bomb grade. With only one small nuclear reactor at Lucas Heights near Sydney, used for making medical and industrial isotopes, Australia will need to have made a big investment in nuclear expertise by the time these submarines arrive.

Morrison’s surprise decision to dump Australia’s commitment to twelve diesel-electric submarines designed by France’s Naval Group in favour of eight US or British nuclear-powered vessels is still being analysed and debated. But one thing is clear. “This is a strategic decision, not a commercial one,” says Steve Ludlam, a former managing director of ASC and, before that, head of Rolls-Royce’s program of modernising Britain’s submarines.

No one is hiding the fact that the new Australian–UK–US technology agreement, AUKUS — which also includes cyberwarfare, artificial intelligence, quantum computing and other frontier science — is about facing up to China, although none of the three leaders mentioned the fact at this week’s announcement.

“If there was any doubt about what Australia would do in an armed conflict between the US and China over Taiwan or the South China Sea, that’s now gone,” Marcus Hellyer, a senior analyst with the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, wrote on Friday. “The US doesn’t provide you with the crown jewels of its military technology if you are not going to use them when it calls for help.”

But we would have been expected to sign up anyway. It is a popular misconception that the navy needs these nuclear submarines to help out in Northeast Asia. Its existing Collins-class boats, and the Oberon-class before them, have operated in that region. Silent conventional submarines like the Collins-class and India’s and Vietnam’s Russian Kilo-class are said to have successfully stalked and “sunk” US nuclear submarines and major surface ships in exercises.

As Canberra strategist Hugh White points out, for the money likely to be spent on the nuclear submarines — exceeding the $90 billion price tag on the twelve French vessels — the navy could have got twenty-four smaller conventional submarines suited to defence of Australia. The twenty-four ultra-quiet subs could also be deployed further afield with replenishment from bases like Singapore, Guam or Japan’s Sasebo.

The latest British and US nuclear submarines benefit from pump-jet propulsion rather than propellers, quieter engines and battery power for lurking, though, and are big enough and powerful enough to carry autonomous underwater vehicles and other new weapons.

Regardless of the technical issues, Thursday’s announcement leaves Scott Morrison with several fires to put out.

China’s reaction to the agreement so far uses routine language to accuse the AUKUS allies of a “cold war mentality.” As the Lowy Institute’s Richard McGregor has observed, Beijing must be aware its own defence build-up has helped create this level of alarm.

Trade issues might anyway be more pressing for the Chinese. The night before the AUKUS announcement, the Chinese commerce ministry fired another salvo in the US–China strategic contest by lodging a formal application to join the Trans-Pacific Partnership, or TPP, a free-trade deal that links eleven countries including Australia. Although the timing appears entirely coincidental, the request painted the United States and its allies as preoccupied with military matters.

Pushed by George W. Bush’s administration, the original TPP was pursued by Barack Obama and negotiated to signature in 2016 by the United States, Japan, Australia, New Zealand, Brunei, Canada, Mexico, Singapore, Chile, Peru and Vietnam. Then, after the Republicans stalled ratification in the US Senate, Donald Trump withdrew the United States from the deal in 2017. Malcolm Turnbull and Japan’s Shinzo Abe got the remaining parties to hang in, hoping for a change of mind in Washington. Biden says the agreement will need to be modified for this to happen.

The Chinese application sits oddly with Xi Jinping’s move back to promoting state-owned enterprises, subsidising selected industries, and separating off China’s internet and cloud storage — each of which would breach the terms of the TPP. But it will throw attention back on Washington’s position when Morrison and Japan’s Yoshihide Suga meet Biden on 24 September.

A more immediate challenge is the rift with France. Morrison has said he started thinking about the switch to nuclear submarines eighteen months ago. It wasn’t until June this year that he broached the idea with Biden — who has final say over transfers of the US nuclear-propulsion technology previously shared only with Britain — at his meeting with the US president and Johnson on the fringes of the G7 meeting. Morrison went on to Paris for an effusive meeting with Emmanuel Macron at which he made no mention of the impending decision. Eventually — about ten hours before the announcement, and after the first leaks by Morrison’s office started appearing in the media — defence minister Peter Dutton notified his French counterpart.

The rift throws into doubt the strategic spin-off from the cancelled submarine contract. France controls vast swathes of the Pacific through its territories’ economic exclusion zones, and French forces add to the West’s array of power in the Indo-Pacific. The political future of New Caledonia and French Polynesia are consequently being closely watched.

The French ambassador to Canberra, Jean-Pierre Thebault — recalled to Paris this week, along with his counterpart in Washington, over what the French foreign minister called “a stab in the back” — has revealed that France had offered Australia the nuclear version of its submarine. The agreed Shortfin Barracuda was actually a diesel-electric version of the Barracuda nuclear attack submarine, the first of which is now operating.

Thebault told the Sydney Morning Herald that his government had asked “at the very high level” whether Australia would be interested in nuclear-powered submarines and had “received no answer.” France had “a high level of expertise in nuclear reactors,” he pointed out. Seventy per cent of the country’s electricity is generated by nuclear plants.

Though closer, at 5000 tonnes, to the size originally sought by the Australian navy, the nuclear Barracuda had three disadvantages. It would not directly contribute to closer strategic engagement with the United States, symbolised by being entrusted with America’s nuclear-propulsion knowledge, nor would it help Boris Johnson’s vision of a post-Brexit “Global Britain” beloved of Anglophiles in Coalition circles like Tony Abbott and Alexander Downer. And, unlike the American and British submarines, whose highly enriched fuel is believed to last the lifetime of the submarines, the French systems are believed to use less-enriched fuel that needs to be replaced every ten years. And the French submarines would not be attached to a nuclear umbrella.

That brings us to the domestic promises Scott Morrison has made about the new submarines: that they will be built in Adelaide, that no civil nuclear power industry needs to be developed to support them, and that the submarines don’t breach the nuclear non-proliferation treaty, signed by Australia, which bars the acquisition of nuclear weapons.

Already the first promise is being watered down. The local content requirement for the submarines now seems to be 40 per cent — no doubt to the fury of Naval Group, which was being held to 60 per cent for the Shortfin Barracuda. Canberra briefings are also testing the idea of building the first one or two lead submarines in the United States or Britain to speed up the program. Meanwhile, about one hundred Australian workers who moved their families to France, and numerous Naval Group staff and contractors living in Adelaide, face a long gap before a new submarine program starts.

Steve Ludlam, the former ASC chief, has no doubt the Osborne yard could handle construction of either of the two most likely models of the Shortfin Barracuda, America’s Virginia-class, which in its latest “Block V” version is 10,200 tonnes and 140 metres long, or Britain’s Astute-class, which is about 7000 tonnes and ninety-seven metres long.

An American naval expert told me that the hull section, which contains the highly secret reactor plant, could be shipped to Adelaide for assembly with the other hull sections. This is already done between the two shipyards building the Virginia-class for the US navy. “Every Virginia-class boat has been built this way, so this approach is well established,” the expert said.

Most Canberra reports suggest the Virginia-class will be the choice of the panel Morrison has set up to advise within eighteen months. But the American naval expert thinks the Astute-class will be favoured. The British boat is about the same length as the Barracuda and, importantly for the Australian navy, has fewer crew requirements — ninety-eight officers and sailors against 135 — than the Virginia-class.

Those who know about these things are cagey about the fuel endurance of the two submarines. Choosing the Barracuda would have required Australia either to build its own uranium enrichment and fuel-rod fabrication plants or to rely on French sources. But the expert said that a US or British design wouldn’t necessarily have fuel rods installed for the submarine’s lifetime.

Ludlam says the naval nuclear capability could be developed without a civilian industry, but that Australia already had expertise in the Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation, which runs Lucas Heights and manages nuclear waste. “We are capable of doing it,” he says. “We haven’t got the same experience as the UK or US, but that’s the value of the partnership.”

The American expert agrees, while observing that it might make the naval program more expensive and pointing out that the US navy’s nuclear-propulsion program is run separately from the nuclear power industry.

But there are those who think a civil nuclear industry will follow, despite Morrison’s promise. “On the issue of nuclear power plants, don’t believe him,” Giles Parkinson, editor of Renew Economy, wrote on Friday. He points out that a poll by the Australian found that forty-eight of the Coalition’s 112 federal MPs and senators support nuclear energy.

“The nuclear lobby will say it is bizarre that Australia could be the only country in the world planning to sustain a nuclear-powered submarine fleet without a civil nuclear industry,” says Parkinson, noting that the Minerals Council of Australia has declared this to be “an incredible opportunity for Australia’s economy — not only will we develop the skills and infrastructure to support this naval technology, but it connects us to the growing global nuclear power industry and its supply chains.”

All these messy details can be pushed into the eighteen-month study behind closed doors, however, along with the costing. Construction in the United States or Britain would probably get eight boats for about US$40 billion (A$55 billion unless China undermines the Australian dollar by buying iron ore elsewhere), though the figure will be much higher if they’re built here.

And on Morrison’s third promise, Washington officials are saying the nuclear-propulsion transfer comes with an insistence the submarines will never carry nuclear weapons. Putting nuclear-armed cruise missiles aboard a submarine, even a conventional one as Israel does, would be the most attainable delivery system for Australia. That now seems ruled out.

The doubts among Australia’s hard realists will no doubt remain: would the Americans really risk a Chinese nuclear strike for us?

Morrison, meanwhile, will be counting on his political fortunes being boosted by what his officials are describing in journalists’ briefings as a pivotal strategic decision to protect Australia. He might be hoping to get the same electoral bounce that some believe Robert Menzies received in 1963, recovering from his near defeat in 1961, after he announced the acquisition of the F-111 bomber. By the time the F-111s went into service in 1973 the threat from Indonesian president Sukarno’s fevered anti-Western posture had disappeared, and the aircraft never saw action.

The new submarines won’t start operating until about 2040 — well after the 2035 date Xi Jinping seems to have set for his own retirement, aged eighty-two, after he has settled the status of Taiwan and other outstanding issues. •